Our Back Pages

The average American has mixed feelings about Hollywood, motion picture capital of the United States and, even for a time, of the world. On the one hand, Hollywood is the dream factory, the land of glamor and “magic,” of grand entertainment, of larger-than-life people (literally as images on a theater screen and because of their indulgent, extravagant lifestyles) worthy of our worship, of financial success and corporate power. To our bohemian, rebellious, and money-grubbing instincts, Hollywood is the quintessence of American modernity. It is what the American character was destined to be. On the other hand, Hollywood is sleaze, conspicuous consumption, artistic mediocrity, sexual predation, the land of the tawdry, the ephemeral, when it is not the palace of the pretentious and self-important. To our Puritan, “agrarian” instincts, Hollywood is all that is wrong with America, the decadent city, the sin factory that has warped the culture beyond repair. Here is the trope of American declension.

It is, with no small significance, that my average countryman can keep perfectly balanced in his or her psyche this conflicting vision of both a place and an idea, for Hollywood is both a geographical and psychological location, a habitation and a state of mind, a destination and destiny. Hollywood is not real unless it is both the good and evil twin simultaneously and interchangeably: The soft corrupt, purulent underbelly of the golden American Dream and the gold of the Dream itself, the sweet yet sweaty smell of fame and money.

Hollywood Godfather and Samantha Barbas’s Confidential Confidential: The Inside Story of Hollywood’s Notorious Scandal Magazine (2018, Chicago Review Press, Inc., 360 pages including index, bibliography, notes, and photos) are about the seedy side of Hollywood, or at least about how two publications—Confidential and the Hollywood Reporter—exploited the seedy side of Hollywood, ill-used the vulnerability of a popular art business that relies on the approval of a mass public. The publications did this in different ways. The Hollywood Reporter through its business practices with the studios and union shakedowns; Confidential through its exposé journalism revealing the immoral (for the time) private lives of movie stars. (If one learns anything from American history it is that immorality is something of a moving target but no less passionately to be extirpated no matter its relative nature.) I suppose the difference between the Hollywood Reporter and Confidential best illustrates the difference between a trade paper and a scandal sheet.

Hollywood Godfather and Confidential Confidential are about the seedy side of Hollywood, or at least about how two publications—Confidential and the Hollywood Reporter—exploited the seedy side of Hollywood, ill-used the vulnerability of a popular art business that relies on the approval of a mass public.

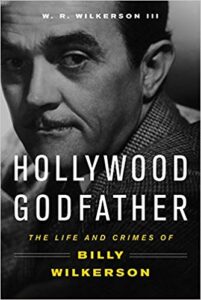

Hollywood Godfather is the biography of Billy Wilkerson, founder and publisher of the Hollywood Reporter, which became the most powerful trade paper about Hollywood and the American movie industry. Wilkerson launched the paper in 1930, after having had led a varied working career to that point including Nickelodeon manager, speakeasy operator, producer of one-reelers, and partner in the New York trade paper devoted to the film business. It was, in fact, his anger at being shut out of the power elite of the film world—loving film as he did, he wanted to be a big-time studio boss—that led him to start the Hollywood Reporter.

As his son writes in Hollywood Godfather: “Filmmaking dreams were replaced by a deep desire for revenge, and Wilkerson made it his life’s mission to crush the studio monopoly and along with it the movie brass. As [director Joe] Pasternak reiterated, ‘Anyone who got in his way he annihilated.’ From that point on, my father would no longer wait for an invitation from Hollywood. Instead he decided to become its self-anointed czar. …

“The idea he was formulating was to start the first daily trade paper for the motion picture industry in Hollywood. With the industry now firmly ensconced in Southern California, Wilkerson knew the demand for such a publication would be high. But he’s also learned during his time with Film Daily in New York that a trade paper’s words could have a powerful effect on the industry; a single bad review could flatten a film. He surmised that a similar publication in Hollywood would give him a club with which to pummel the men who had shut him out of ‘their’ business.” (HG 52)

That Wilkerson was a dyed-in-the-wool Southerner (with unreconstructed views of blacks as they were never allowed to work or patronize any of his establishments, HG 187) and a devout Catholic (despite having been sexually propositioned when a child by a priest, HG 22) made him feel even more an outsider in an industry mostly dominated by Jews. The fact that the many Jews who were power brokers in Hollywood were themselves ostracized by the non-Jewish elite of Southern California and were, in many respects, socially precarious, was something that Wilkerson would take advantage of with the various restaurants and clubs he would open during his career in Hollywood. (HG 59) His high-class places inspired by his love of Paris—Café Trocadero, Ciro’s and LaRue’s—were refuges for Hollywood stars, their agents, and their employers. They were in fact where he got the lowdown on what was going on in the movie-making world.

Wilkerson himself had something of a precarious existence as he suffered from a gambling addiction, apparently inherited from his father Richard “Big Dick” Wilkerson (a colorful nickname if there ever was one being obscene, juvenile, fantastic, and innocuous at the same time, a bit like novelist Ian Fleming’s Pussy Galore). According to Hollywood Godfather, Wilkerson the younger went through hundreds of thousands of dollars at the race track and the gambling tables of Nevada and Monte Carlo. (It seems clear from the son’s account that Wilkerson was a terrible gambler. The takeaway here: never have a fever for some risky activity unless you are good at it.) If not for loans and bailouts from friends like the eccentric producer/aviator Howard Hughes and the less eccentric producer Joe Schenck, and shakedowns from the studios through his mob connections, Wilkerson, who liked to live large and elegantly, would never have survived or at least would never have been able to maintain control of the Reporter which, despite the success of his other business ventures, remained the core holding of his empire and the one most important to him. Other projects bored him after a while but never the Reporter.

“Confidential magazine,” Barbas melodramatically writes, “grew, like a weed, out of the dark and paranoid soul of the early 1950s.” Let us say it grew out of the social contradictions that afflicted and still afflict our culture, the main one being, to borrow from James Baldwin, the need to smash taboos for liberation’s sake while still being imprisoned by one’s fascination with and need for the social coherence they provide.

The Hollywood Reporter was started during the halcyon days of the Hollywood studios that had actors and directors under company-friendly contracts, owned the theaters where their movies played, and virtually controlled the lives of their employees. Confidential emerged in 1952 when Hollywood was undergoing rapid change: the studios were up against a popular new medium called television which was dramatically draining their audience; the courts forced them to relinquish their theater ownership—a big blow; and as their market tightened they released many actors from their long-term contracts and thus began to lose control of the industry they created.

“Confidential magazine,” Barbas melodramatically writes, “grew, like a weed, out of the dark and paranoid soul of the early 1950s.” (CC 17) Let us say it grew out of the social contradictions that afflicted and still afflict our culture, the main one being, to borrow from James Baldwin, the need to smash taboos for liberation’s sake while still being imprisoned by one’s fascination with and need for the social coherence they provide. Now, that is a melodrama, if there ever was one. And that is exactly what Confidential represented, the Puritan urge for the prurient in the name of virtue, to tickle the libido while condemning its stimulation.

Robert Max Harrison, a hustling, street-wise Jew (non-religious as an adult) from Manhattan, founded and published Confidential, it having morphed from a series of cheap “girlie” cheesecake magazines that he put out after WWII with names such as Whisper and Eyeful. Barbas is right in tracing Confidential’s pedigree through the sexploitation of detective magazines, the salacious stories of “white slavery,” murders, and prizefighting in papers like the National Police Gazette, the Hearst newspaper style of yellow journalism, and the Confidential books—New York Confidential, Chicago Confidential, Washington Confidential, and U.S.A. Confidential— that came out between 1948 and 1952 “[written] in a crude, muckraking style, they offered an alleged ‘behind the scene’ expose of deviance, crime, and corruption in American cities.” (CC 23) Confidential blended various aspects of the pulp world of sensational, less-than-reliable journalism, sort of the equivalent of the freak gossip of a deranged fan magazine with punk-style, second-rate, vernacular writing, something I would call fame porn.

Confidential, at first, inspired by the 1951 televised Kefauver hearings on organized crime, focused on crime and outing Communists. The latter was something that the Hollywood Reporter had been doing even earlier, in part, as a cynical ploy to avert attention from that magazine’s connection to an organized crime shakedown of the major Hollywood studios and, in part, because Wilkerson, devout Catholic that he was, intensely hated pinkos, liberals, socialists, leftists, and commies of all stripes. (Nothing destroys a country quicker than fanatics advocating a welfare state for lesser and lazy breeds!) Indeed, the Hollywood Reporter was responsible for forcing studios to blacklist actors, directors, and writers. It was all part of Wilkerson’s ambition to be a power broker, a man who could bring the studios to heel. By the time Confidential came to the “Red Smear” game, the ground had already been fairly well plowed and harvested by the Hollywood Reporter, which had come earlier and had more clout. But Confidential soon shifted to where audience interest truly was, the scandals surrounding the private lives of Hollywood actors, particularly revelations of homosexuality (the kiss of death for any career at that time) and interracial sex (also fatal or nearly so, especially between a black man and a white woman). Confidential became, in effect, what the standard Hollywood fan magazines of the 1920s to the 1940s—Modern Screen, Photoplay, Hollywood Mirror, Motion Picture, Screen Romances, Screenland, Screen Book, and a dozen others—sometimes aspired and tried to be: not supporters or creatures of the Hollywood establishment which they were, but a form of subversion against it. (See Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine: A History of Star Makers, Fabricators, and Gossip Mongers by Anthony Slide, 2010). The Hollywood Reporter was an arbiter; it judged and ranked fan magazines, chastising them when they became too out-of-hand or unruly in their revelations, too tasteless. Confidential was the subversion of taste itself. Anything that entertained was entertainment. But only the naïve were under the impression that entertainment was not or could not be a weapon.

The Rules Have Changed Today

Fame porn was objectionable on two counts. First, it was libelous in invading the privacy of famous people and revealing things that were either not true, only partly true, or were entirely true but something the person did not want known and, most important, had a right to keep concealed. In short, great fame did not forfeit the necessity or the right to a private life. Second, the nature of these revelations often tended to be sexual and highly descriptive (though tame by today’s social media standards) and thus at the time of the magazine’s heyday in the mid-1950s could and often was considered obscene. Confidential was, as Barbas rightly observes, ahead of its time in that it existed before New York Times v Sullivan (1964) which ended criminal libel—the grounds upon which California State Attorney Pat Brown prosecuted the magazine in 1957–and before the general public acceptance of hardcore pornographic films in the 1970s ended most obscenity laws. The rules changed but too late to help Confidential, although as Barbas points out fame porn became institutionalized in publications like the National Enquirer and People, websites like TMZ, and a variety of television programs.

Barbas’s basic contention is that a conservative impulse that governed, oppressed, really, the 1950s, brought Confidential into being: its exposes largely being fueled by homophobia, racism, sexism, and rightwing anti-communism. But it would seem that an equally conservative set of forces were operating to drive the magazine out of business: Hollywood, as damaging the reputations of their stars was bad for the bottom line; government law enforcement that wanted to control expression and morals because they felt it was power they were entitled to exercise; guardians, reformers, and institutional gatekeepers who wanted to “protect” children from harmful influences, always a proffered reason for censorship. In the end, the public loves or loves to hate the sinful voyeurism, the vicarious thrill of taboo-busting. Confidential was crushed, in the end, but not the impulse that drove it.

Confidential’s fame porn was a de-legitimatizing machine and, in the long run, helped its victims by de-legitimatizing the very taboos the breaking of which constituted scandal: homosexuality, interracial sex, cross-dressing, all marginalized habits that had to be suppressed. The taboos were undone because Confidential inadvertently widened the concept of consent as a liberating act.

And that impulse was not actually conservative but something more like nihilistic. The obvious liberal platitude that Confidential legitimated was free speech and a free press. But more important was the cynical view that nothing and no one are sacred because establishments and canons are made to be unmade or de-legitimatized. Barbas rightly states that “Confidential—however crude and outrageous—became a force of liberation in American culture.” (CC 152)

But here is how that worked: Confidential’s fame porn was a de-legitimatizing machine and, in the long run, helped its victims by de-legitimatizing the very taboos the breaking of which constituted scandal: homosexuality, interracial sex, cross-dressing, all marginalized habits that had to be suppressed. The taboos were undone because Confidential inadvertently widened the concept of consent as a liberating act. In this way, if anything, far from being conservative, the magazine, regardless of the political and social beliefs of its publisher and writers, ultimately enabled the left to politicize new identities by arguing for the expanded power of consent if an adult is to exercise the full privileges of being an adult. But this happened because as a capitalist enterprise Confidential’s de-legitimatizing taboos opened the door for new publics, new niche audiences, fresh ways of democratizing the society by simultaneously “lowering” taste but maximizing public virtue through inclusion. Let us fully understand how the rules have changed today.

I think Barbas misses or misplaces some of the significance of the magazine because she trapped by such a stereotyped view of American society in the 1950s. (For instance, why does everyone, as Barbas does in this book, bring up June Cleaver as the major trope of the white housewife of the 1950s and never consider Alice Kramden of The Honeymooners, a television show that was just as popular if not more so than Leave It to Beaver and which spawned the animated series The Flintstones, a far more influential program than Leave It to Beaver ever was, or Lucille Ricardo in I Love Lucy which was even more popular than The Honeymooners or Leave It to Beaver? Both Alice and Lucy were different models of the white housewife.)

Confidential Confidential is the third book to be published on the magazine in the last 15 years. I reviewed the other two about ten years ago in The Figure in the Carpet, a now-defunct publication of the WU Center for the Humanities. There are a few mistakes in Confidential Confidential, the most annoying is the author identifying the John Wayne film The Quiet Man as a western (CC 209). It is not.