Pulp is both a material description and a genre designation. Pulp is the lowest quality of paper, seemingly discolored by nature; the oils of the hand only exacerbate its palpably low value. Pulp as a far-reaching aesthetic category is the lowest quality of literature, melodramatic action-driven tales of the most unsavory members of our population at their most lurid. It is true that one often must go to low places to find the most over-the-top material. In the sordid part of town, within the grayest alcove, through the threadbare storefront and behind the curtain, one could always indulge in a taste of the distasteful. Yet, while the “low” part of town may be a scene for some to slum for wanton pleasure, it also can serve as a site for clandestine insurgence. Those with sleazy appetites and those with radical aims tend to avoid the regulating authority of the same hegemonic gaze. In part, what Andrew Nette and Iain McIntrye’s edited collection, Sticking it to The Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 reveals is that the writing we deem low in literary quality or moral esteem often overlaps with those who are socially marked as society’s lowest. At the margins of the literary world the seedy and subversive are natural bedfellows. For sure, Sticking It To The Man does not consider just any pulp fiction books; these are the stories of folks who have had enough of their designation as low and choose to rise up and challenge “the man” whose standards cast them down.

Those with sleazy appetites and those with radical aims tend to avoid the regulating authority of the same hegemonic gaze.

It is not merely the second-rate prose styling of hacks or the disregard for editorial oversight that mark the books considered in this engaging edited compilation. Sticking it to The Man is a thematic collection that focuses on novels that sought (some more successfully than others) to capture the sensations of various “counter-cultures” of the post-WWII era to the rise of Reagan. Although four decades worth of pulp is chronicled the book historicizes the works included as those of the “long 1960’s.”(1) This term rightfully acknowledges the porous nature of historical epochs and the fact that while many social movements found their zenith in the mid-late 1960s, many began to bubble in the 1950s or fizzle in the late 1970s. The thematic corralling of “revolution and counter-culture” has the effect of establishing the wide and chaotic terrain. In one respect, this is quite appropriate. The “long 1960’s,” particularly the 1960s, were a hectic time of many social movements; some allied, some precarious, and some contentious. As such, leather-clad black power radicals, bearded campus rebels, free-loving hippies, their more antagonistic yippie cousins, vigilantes of various motives, chic street-level hustlers, feminist crusaders, and queer folk in search of safe places to love all come together to form a dizzying agglomerate of socially marginal figures turned center-stage heroes and villains. From novels that are purposefully bizarre to those that are politically brazen there are no dull pages to be found in this collection.

Sticking it to the Man follows the organizational model that the folks at PM Press established with their first, and also quite absorbing, collection, Girls Gangs, Biker Boys and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950-1980. Consisting of more than fifty entries written by pulp scholars, pulp authors, and influential aficionados alike the variety displayed in Sticking it to The Man’s content strikes a delicate balance between introductory survey and detailed exploration. The entries range from profiles of seminal authors like Ernest Tidyman, Barry Malzberg and Donald Goines, to rundowns of pulp subgenres like the late 1960’s “campus revolt novels” and “the golden age of gay erotica-1969-1982.” On the whole the entries are each well-structured and symptomatic close readings of obscure novels are offered as adjunctive details to otherwise more comprehensive sketches of likely unfamiliar content. That is to say, this is a resource for the novice and the knowing fan alike; a beginner’s guide curated by enthusiasts. However, the excitable nature of fandom peeks through a bit in the editorial organization. At times chapter topics jump from one to the next without any clear thematic continuity. For instance, a reprinting of Jenny Pauscaker’s fine ten-page survey of “Adolescent Homosexuality Novels” is, without much clear logical transition, followed by Nette’s brief single text consideration of John A. Williams’ exploration of the Black Power Movement in the 1971 novel Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light. At the level of enjoyment this piecemeal approach makes little difference; actually, when reading cover to cover, the disjointed organization inspires an experience in sustained surprise, unexpected turns that lead to unexpected insights. However, from a stricter scholarly perspective, a tad more attention to sequencing would enhance the narrative quality of the collection as a whole.

Well aware of its far-reaching historical premise and wide variety of social movements that qualify as “counter-culture,” Sticking it to the Man makes plain that it is not a “definitive history.”(3) Such a history would need to be encyclopedic. As such, the majority of books, or book series under consideration, are examined as much as relics of specific cultural contexts and/or pulp sub-genres, as they are singular texts. Perhaps, traditional paradigms like “great works” or “great authors,” models that generally work to marginalize popular literature, are ultimately unavoidable. Even at the fringes of literary standards, canons seem to take shape. Yet, the case of pulp canon-building is an especially arduous task, and if this book is not “definitive” that is not to say it is not diligent. Pulp Fiction was developed primarily as a commercial enterprise more than as an aesthetic movement (which is not to say a pulp aesthetic was not produced). As far as publishing houses like Paperback Library, New American Library, and Dell were concerned the objective was product quantity, not literary quality. Books were produced at break-neck speed, with little regard for editorial oversight and an emphasis on action not introspection. Moreover, shifts in thematic trends, from the mainly White male adventure stories set before/during the World War period to Post WWII counter-culture escapades, did not change these central facts. Pulp producers and authors were willfully malleable to whims of consumptive trends. These facts are generally used for wholesale slander or dismissal of pulp as sleazy ephemera; yet, Sticking it to The Man pushes aside the falsity that all Pulp was derivative, and identifies and explores why some books, or authors, were more impactful than others. At the same time, the collection acknowledges that in the shadow of seminal works, much pulp was, without apology, derivative and urges its readers to ruminate on what it was that was so appealing about the formulaic sensationalism afforded by the bulk of pulp.

Pulp fiction was developed primarily as a commercial enterprise more than as an aesthetic movement (which is not to say a pulp aesthetic was not produced). As far as publishing houses like Paperback Library, New American Library, and Dell were concerned the objective was product quantity, not literary quality.

At core there are two concentric spheres of pulp’s appeal under consideration; one sphere is books that offered cartoonish renderings of the social maelstrom of the “long 1960’s,” the second is those books whose focus on social or political radicalism “portrayed and catered to people previously ignored by the publishing industry.” (3) Indeed, during the “long 1960’s” pulp was a vehicle for both voyeuristic romps and radical realism and, as they say, therein lies the rub. One person’s earnest commitment to social justice was easily transformed into another’s titillating adventure. For every innovative voice made marginal by biases of mainstream publishing there are ten derivative works by lifetime hacks. As such, some of what can be found amongst pulp of the “long 1960’s” can be termed as exploitation literature, which sought to make a quick buck on fetishizing the social action for its more dramatic features. Many of these novels, the collection suggests, were harmless enough. However, not all were good-natured romps that recognized the ideals of free love, mind-expanding drugs or heroic revolutions as ideal subjects for melodrama. However, some works of the period are shown to be quite reactionary, taking on dynamics of social unrest in a manner that mirrored the conservative backlash of Nixon and Thatcher. Novels like Parley J. Cooper’s The Feminists, and Richard Allen’s Demo (which purports to be a “study”) offer dystopian visions of the reign of brutal matriarchies and commie student protesters. The explicit sex and drug use found in such novels, gestures toward the thin line reactionaries walk between bombastic anger and repressed desire. This partnership of wrath and want is only exacerbated by the usually “square” vantage point of the author. Such books are laughably bad and Sticking it to The Man emphasizes that much of the fun of pulp comes in just how clumsily hackneyed it can be.

Yet, the proposition that fun can be had in the knowingly bad is not likely to be entirely compelling to readers for whom quality literature that reflects their lives is sorely lacking. Fortunately, this collection also makes clear that fine writing is hiding in this vast canon of schlock. In fact, some is quite innovative, not necessarily in the sense of alignment with a socio-political movement, but in introducing fresh voices and innovative styles to readerships that were often discounted, or even regarded as essentially illiterate, by mainstream publishers. For instance, Kinohi Nishikawa’s exploration of Iceberg Slim shows the hustler-turned-author offering a provocative deviation from the affected stylings of the “square” hacks. Slim, known otherwise as Robert Beck, had been a pimp and his aptly titled autobiographic bildungsroman, Pimp: The Story of My Life, was a story untold in the realm of published novels, by a voice unheard by the reading public. Written at a nexus of terse vernacular and fluent prose, Slim would inaugurate an entire subgenre of pulp called, “Black Experience Books,” and become the most famous pimp in American history. Perhaps the latter is an infamous accomplishment; nonetheless, it exemplifies the distinct role that pulp played in bringing notoriety to otherwise obscure writers.

Fortunately, this collection also makes clear that fine writing is hiding in this vast canon of schlock. In fact, some is quite innovative, not necessarily in the sense of alignment with a socio-political movement, but in introducing fresh voices and innovative styles to readerships that were often discounted, or even regarded as essentially illiterate, by mainstream publishers.

When considering the limited opportunities granted to Black writers, gay writers, and women writers, not to mention those writers who tick multiple boxes, it is clear that pulp offered a humble, and in its own ways exploitive, outlet to a host of writers who had been shut out of the publishing industry. This fact made for a distinct type of pulp writing; those that focused on experientially grounded realism and geared toward readerships eager to see themselves in outlandishly heroic and banally quotidian contexts alike. This is not to romanticize all pulp written by minority authors. Indeed, a great many were as purposefully scandalous and formulaic as anything written by heterosexual White males. In the vein of Michelle Wallace’s argument that “positive” Black representation only works to legitimize the prejudicial logics of “negative” Black representation¹, everyone should be entitled to pulpy schlock just as they are to literary masterpieces. Nonetheless, novels by the likes of Iceberg Slim, Chester Himes, Ann Bannon and Betty Collins shared shelf space with paperbacks that sought nothing more than a quick romp through a familiar formula. This mixture of so many works raises a most intriguing and difficult-to-reconcile issue at the heart of this edited collection: Is all pulp fiction equally “low”? Perhaps no content can overcome the implications of those greyish pages and uproarious covers.

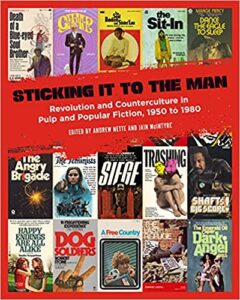

The study of pulp fiction novels entails the study of the materiality of text. As noted, the way these paperbacks are made and the way they look, relates to their literary value, or lack thereof. It is thus appropriate that Sticking it to The Man is a uniquely enthralling textual object. Ironically, its large format (8×10) and polished production value make it not only a useful scholarly resource but also a coffee-table adornment. As one who is constantly surrounded by books and works among those who also are, few books have garnered more head-turning interest from passersby than this one. In particular, the assemblage of high-resolution images of pulp covers (roughly a dozen of which checkerboard the front cover) is Sticking it to The Man’s most attractive quality. Fortunately, the cover art is only a taste of the nearly 350 lush pulp covers found within. Most any fan would deem the variety and high quality of these images worth the price of the book itself. Every chapter is accompanied by the cover(s) of the novels it considers, many of which are quite rare. Ann Bannon, author of the path-breaking lesbian pulp collection, The Beebo Brinker Chronicles, was apt in saying of pulp fiction that, “the covers entice.”² Unlike the ashen paper that is the backdrop for pulp prose, pulp covers are provocatively, often gaudily, decorated. The begrimed pages and loud covers make a perfectly odd partnership to convey the ephemeral sensationalism of the genre. Like the movie posters of pulp’s more (de)famed filmic counterpart, exploitation films, pulp covers are easily identifiable. From the noir-esque illustrations of the 1950s and early 1960s to the theatrical montages of the late 1960s and the 1970s, the consistent visual aesthetics of pulp covers, despite disparate subject matter, may be their most pervasive cultural resonance. Paraphrasing Justice Potter Stewart’s infamous utterance in regard to pornography, one knows a pulp paperback when one sees it. In this respect, the pulp industry relied on inverting the old adage and suggesting that you can tell a book by its cover.

This mixture of so many works raises a most intriguing and difficult-to-reconcile issue at the heart of this edited collection: Is all pulp fiction equally “low”?

Pulp’s capacity to viscerally entice seems, in turn, to limit the perceived depths of its worth. Offering fleeting sensations at low costs, there is a shame that lingers in the pleasures these paperbacks deliver. Perhaps this is why pulp is widely denounced but also widely read; it reflects taboo yearnings so shared that we all agree, often wordlessly, that they do not exist or at least not amongst us. In this respect, all pulp is “counter” to the mores of our mainstream “culture,” radically disrupting ostensive social standards, not to reform them, but to invert them, turn them inside out in order to play with their guts. Pulp of the “long 1960’s” knowingly doubled down on the brashness of pulp’s possibilities upon the premise that such cultural surgery is equal parts brutal, experimental, and revolutionary.