When pianist Herbie Hancock won an Oscar for the original film score of the 1986 film, Round Midnight, it was if popular culture was bestowing a feverish kiss on the cool brow of a dying art form, jazz. After all, the film itself was about a dying jazz musician, perhaps in his way as mythical as the dying gunfighter in Don Siegel’s 1976 film, The Shootist. The jazz musician was, like, the gunslinger, one of the last signs of an American masculine swagger born of the frontier (in jazzspeak, “the territories”) and the transgressive mystique of border crossings (in jazzspeak, “fusion”). As an image, the hip, subversive, argot-spewing jazz musician, like the rapacious, vengeful, cold-blooded gunfighter, was the birth of the American cool. All of this mythmaking was couched in tragedy: the misunderstood, socially isolated gunfighter and the suffering, pain-wracked jazz musician, also a misunderstood isolator. Hancock underscored the film’s presentation of the tragic jazz musician in his acceptance speech which emphasized the jazz musician’s lonely sacrifice for his art.

Hollywood had long loved the gunfighter and now with awarding the film scoring Oscar to a jazz film, it was, finally, recognition and redemption for jazz: As Hancock wrote in his autobiography when he learned he had been nominated for the award, “… I knew how much that Oscar would mean to jazz players, who often feel like the redheaded stepchildren of American music …” What made this Oscar all the more significant was that it was not given to a professional film scorer who had written a jazz soundtrack but rather to a reputable jazz musician who had written only a handful of film scores while pursuing his main career as a performing musician, not as a composer. Hancock did something not even the great jazz composer Duke Ellington, who wrote a few film scores himself including, most famously, the score for Otto Preminger’s 1959 courtroom drama, Anatomy of a Murder, was able to do. For Hancock, this was a majestic accomplishment in what has been an extraordinary career.

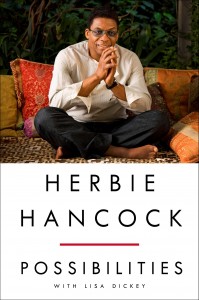

As Hancock explains in Possibilities, his relationship with jazz, the art form that brought him to the attention of the public and established his reputation as a first-class musician, has always been problematical. As a child, he thought he would be a concert pianist, the dream of performing classical music being rather common among many young, well-trained jazz musicians both now and of an earlier time. It was not racism that prevented Hancock from being a concert pianist, as it prevented the classical careers of other black performers of his generation and before. Hancock fell in love with improvisation in high school when he was introduced to some George Shearing records. Hancock’s career, once he decided he would be a professional musician, has been something of a shift-shaper and the response of some segments of the critical establishment as well as some of his friends to these changes has been, at times, frustrating to Hancock. For instance, when he was recording the album “Future Shock” which would produce the 1983 smash hip-hop single,“Rockit,” his sound technician, Bryan Bell expressed doubts about the project, to which Hancock responded angrily, “‘When I stopped classical music and went to jazz, I got crap for it. When I left jazz to do space music, I got crap for it. When I left space music to do funk, I got crap for it. And when I left funk to do what I’m doing now, I’m still getting crap for it.’” (Emphasis Hancock) Hancock was always a sellout or a traitor to somebody. When he was performing with trumpeter Miles Davis in the 1960s, in what was considered the best, most innovative mainstream jazz band in post-World War II musical history, he was, for the jazz critical establishment, the young jazz genius on the piano. Even veteran, take-no-prisoners pianist Oscar Peterson said at that time that Hancock was his favorite of the younger cohort of pianists that included McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett, all twenty-something young guns.

“‘When I stopped classical music and went to jazz, I got crap for it. When I left jazz to do space music, I got crap for it. When I left space music to do funk, I got crap for it. And when I left funk to do what I’m doing now, I’m still getting crap for it.’”

When Hancock left Davis to form his avant-garde group Mwandishi (Swahili for composer), surrounded by electronic keyboards and playing with fellow black musicians who had adopted Swahili names and dashikis, he was condemned by the modernist critics who loved Davis’s acoustic mid-1960s music. When he disbanded Mwandishi because it was losing too much money (he subsidized the band with the publisher’s royalties he was earning from his hit composition, “Watermelon Man,” which has become one of the most popular jazz tunes ever written), and decided to do funk music with a new band called The Headhunters, he was condemned by the avant-garde types and free jazz lovers. When the album “Head Hunters” came out in 1973, it was, without question, the most popular jazz record ever among black college students across the country (I was one of them), a group of fans who would never have listened to either the Miles Davis records or the Mwandishi albums and did not know or care that Hancock had recorded “Maiden Voyage” in 1965, considered one of the best jazz albums of the 1960s, for some, one of the best modern jazz albums ever. But when Hancock went back to doing standard acoustic jazz with VSOP quintet (Very Special Onetime Performance) and playing piano duets with Chick Corea, the hip, young black listeners he had gained with “Headhunters” felt he had betrayed them, although traditional jazz critics now loved him again. A newer version of those listeners returned to the fold when Hancock made the aforementioned “Rockit,” which traditional jazz critics thought was awful.

In short, Hancock’s career has been a sort of high-wire act, attracting and disappointing audiences and critics, being successful both critically and commercially but never quite at the same time with the same group of people. When Hancock made “Headhunters” and “Rockit,” jazz critics thought he was going after the money; when he made acoustic jazz records like “VSOP” and the duets with Corea, the young and hip followers of his hip-hop and funk records thought he was betraying them by being a jazz elitist. As Hancock writes when German audiences booed him for playing electronic music at a particular concert, “Those audiences seemed to believe that the artist should be doing whatever they wanted him to do, even if it meant staying stuck in the past.” (Emphasis Hancock) Later he writes, “Twenty years had passed since I joined Miles Davis’s quintet, and if I had spent my time paying attention to what other people wanted me to do, I would never have explored any other styles of music. Why was it so difficult for people to believe that a musician might want to venture into new music from an artistic standpoint rather than a financial one? I’m not saying I didn’t want my records to sell—of course I did! I wanted my music to reach as many people as possible. But the difference is, I never chose what kind of music to make strictly for the goal of maximizing sales. I made the music my heart led me to make—and some records sold millions of copies, while some sold very few.” Those who know jazz history well will recall that one reason the clarinetist quit the business was because audiences wanted him always to play his monster hit, a cover of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine,” and would not accept him doing anything else. Hancock wanted to escape that form of captivity. In this way, Hancock has never become an “oldies” act or an act whose appeal is built on memory. Hancock has been a jazz musician who has been in conflict with limitations of the art form, with its elitism (which he rails against several times in Possibilities), with its sense of self-pity at being marginalized. (Hancock emphasizes several times in the book how he had no sense of identification with victimhood. This made his engagement with his racial identity take on an air of experimentation and detachment, which, for some readers, will be refreshing, and for others distressing.) So, his winning the Oscar for the music of Round Midnight is a more complex accomplishment than it appears on the surface.

Possibilities is an informative autobiography about being a professional musician and about the impact of electronics on music-making. Hancock, always of an engineer’s turn of mind, has had an abiding interest in the technological aspects of music, employing synthesizers, electric pianos, vocoders, and other electronic devices throughout his career, almost always when these machines first appeared. The tension of contrast in this book is Hancock’s pursuit of technology as an important artistic dimension of modern music-making and his exploration of Buddhist chanting as a form of personal fulfillment. (Incidentally, the Buddhist chant used repeatedly in the book can be heard in singer Jon Lucien’s 1975 song, “Creole Lady.”) Hancock always has given the sense of being new and this intensified his being a pathbreaker. The book provides rich portraits of Donald Byrd (Hancock’s first jazz employer), Miles Davis and drummer Tony Williams, in particular. There is a less-than-flattering account of a young and rather insufferable Wynton Marsalis’s tour of duty with the VSOP band. And there are deeply personal stories about his sister, his mother, his marriage, and his bout against crack cocaine addiction.

Hancock’s autobiography is highly recommended.