The first pair of jeans I chose for myself felt like hope. Eleven years old, I was about to become the All-American Girl Next Door, Mary Ann on Gilligan’s Island. Giddy with possibility, I wore my new jeans straight into the bathtub, sitting patiently while the water cooled and turned bluish gray and the sodden denim sat heavy on my thighs. Out to the summer sun to shrink them dry, and then I dumped my mom’s Clorox into the washer (I had the process backwards) to fade that pristine, too-perfect dark blue. As soon as they were dry again—and so stiff they could stand on their own—I scrubbed the thick seams with sandpaper, then spent hours jabbing a needle into the tough fabric because I just had to embroider pink and orange flowers growing from the hem. I wore them for six months, and then they were just right.

More jeans followed, changing shape and color with the decade, growing pricier and more elaborate, and fashion stole the break-in process and commerce outsourced it. It was an all too American trajectory: from plain to luxe and from egalitarianism to exploitation. Yesterday, hunched over the keyboard in my home office, I ordered Sherpa-lined sweatpants, made in China, on Amazon, which is a sentence of losses.

The story of blue jeans is an American romance, and we may have spoiled the ending.

Levi’s

After watching nuggets slip through the Gold Rush miners’ flimsy pockets, a dry-goods merchant named Levi Strauss ordered bolts of coarse brown canvas so he could sell sturdier workpants. Soon he switched to a fabric first milled in France: serge de Nîmes, hence denim. (A similar fabric was milled in Genes, hence jeans.) The threads were dyed deep blue with plant indigo, then tightly interwoven with white or gray. The result was dark and durable, hid the dirt, showed no weakness.

In a stroke of genius, the tailor Jacob Davis suggested copper rivets for the stress points. The two men registered their rugged, simple “waist overalls” in 1873—U.S. patent number 139,121. Every pair looked alike. Miners bought up the $1.46 overalls and wore the hell out of them. In jeans, you could crouch for hours beside a California stream, happily sifting gold from the gravel without ripping your crotch seam. Cowboys stole the idea and shrank their jeans tight, no extra fabric to flap or chafe as they roped calves and broke wild horses.

Yesterday, hunched over the keyboard in my home office, I ordered Sherpa-lined sweatpants, made in China, on Amazon, which is a sentence of losses.

In the first nine decades, there were only three significant changes. As suspenders lost favor, belt loops were added. To save materials during World War II, the rivets were removed from the watch pocket (that cute, now useless pocket below the waistband) and the base of the button fly (where they had a disconcerting tendency to heat up when you squatted in front of a campfire). In 1954, a zippered fly arrived.

Serious change started in the Sixties, with its explosion of flowers and freedom. People added rainbows, patches, fringe, and studs to make their jeans their own. In the Eighties, jeans became fashion, and everything changed.

Today, the original Levi’s 501®s for men comes in at least three stonewashes, four dark washes, and five medium washes; garment-dyed gray or Iris Purple; eggshell, black, green, white, and multicolor. “Made and Crafted” 501®s are selvedge denim finished with whiskering and fading. Customizable 501®s are overdyed with a pattern of your choice laser-etched onto the denim. Other 501®s are pre-ripped (though not at the crotch), stretch, cropped, or ready to be personalized with Lego dots. You can buy Vintage 1947, 1954, 1955, 1984, or 1993—or blow $265 on a custom mashup that is half 1937 and half 1993.

They are all imported.

I try to imagine Levi Strauss clicking through his company website, his fine Bavarian brow furrowed by all this unnecessary choice. When he chose a sturdy French upholstery fabric, he could not have known that it would wind up telling the American story. Or that the American story would be a global story. Or that our symbol would be plucked away from us.

Rock & Republic

The jeans of the American West were fit for backbreaking work but eager for a flash in the pan fortune. As I read their saga, I decide that Walt Whitman would have celebrated these cheap, democratic pants. Stained by clean sweat and earth, they signal robust youth and freedom and wild dreams and a casual aversion to fuss, a determination to shape one’s own future.

Maybe Whitman even wore blue jeans. He was still around…. I search eagerly for old photos, but instead of finding evidence for my fancy, I stumble on two commercials, filmed in 2009 and narrated with Whitman’s poetry. Seems Levi Strauss & Co. was a step ahead of me.

In the video, it takes a minute to realize the giant “America” letters slanted against a hillside are look-at-me neon, because the first commercial is shot in a heavily shadowed black-and-white. Even the fireworks are gray, no hot pinks and golds and lime greens to distract us from the explosive drama of celebration and protest, Americana and urban grit. Running like a river beneath the edgy images is a voice believed to be the poet’s own, recorded years before on a wax cylinder.

… Walt Whitman would have celebrated these cheap, democratic pants. Stained by clean sweat and earth, they signal robust youth and freedom and wild dreams and a casual aversion to fuss, a determination to shape one’s own future.

“Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich,” Whitman recites. “Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law, and Love.” When he wrote those words, freedom and law were not seen as opposites. Both could coexist with love.

The second “Go Forth” commercial uses an old tape of Will Geer (before he was Grandpa Walton) reading “Pioneers! O Pioneers!”: “We must march my darlings, we must bear the brunt of danger,/We the youthful sinewy races, all the rest on us depend.” This one makes me a little nervous, with its call to arms—“Have you your pistols? have you your sharp-edged axes?”—set against footage of young people banding together to protest or running with lit torches. The images jangle in my head. By pressing blue jeans into a contemporary frame, Levi Strauss & Co. has complicated their original virtues.

Granted, I am doing the exact same thing, exploring American jeans through the filter of contemporary marketing, environmental impact, global economics, and pandemic, and testing to see if our contribution to the world’s wardrobe still holds its own. That, after all, is the point of jeans: Those virtues were made to endure. They should weather as well as the 1890s Levi’s found twenty feet underground in the Yukon, intact. Or the pair from the Thirties that were tied to two bits of rope and used to tow a car four miles, over a hill, to a service garage.

Looking for more about the ad campaign, I find a fond reminiscence in Slate. When I scroll down, the story is interrupted by an ad for ACE sweatpants.

“They All Wear Levi’s” 1930s advertisement from Levi Strauss & Co. Archives. (Courtesy Contemporary Jewish Museum)

Citizens of Humanity

“Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” someone asks Marlon Brando’s jeans-clad character in The Wild One.

“Whaddaya got?” he shoots back.

Two years later, James Dean sealed the trope in A Rebel Without a Cause, making blue jeans and a white T-shirt spell daring and a sexy cool. They fit differently than other pants, emphasized the length of the leg, the curve of the tush. They made authority figures nervous.

By the Sixties, jeans belonged to the young and the restless. A journalist friend, Susan Margolis Balk, moved from a buttoned-up New York publishing house to Rolling Stone, where everybody wore jeans, and she was struck by the irony: “Just when ambition was flowering, instead of a ‘dress for success,’ God help us, we chose to look like workers. My editor was a Texas bad boy, and he wore tight jeans and a black velvet blazer….” Her voice drifts as she remembers. “I think men were more physically present in jeans. When a man is wearing a three-piece suit, he’s hiding.”

They fit differently than other pants, emphasized the length of the leg, the curve of the tush. They made authority figures nervous.

Some of Balk’s friends packed their Levi’s when they shipped out to Vietnam; others wore them to protest the same war. United Press International described ministers marching in Alabama as wearing the “blue denim ‘uniform’ of the civil rights movement over their clerical collars.” Jeans, historian Tanisha Ford tells Smithsonian, “not only recalled the work clothes worn by African Americans during slavery and as sharecroppers, but also suggested solidarity with contemporary blue-collar workers and even equality between the sexes.”

Solidarity remained the point—with Black sharecroppers, White laborers, feminists, gay men…. Martin Luther King Jr. wore jeans; so did Harvey Milk. In Latin America, too, jeans became a uniform of political struggle; an ad in an Argentinian newspaper pronounced them “joyful and resistant.” In 2006 in Belarus, a protester tied his denim shirt to a stick as a makeshift flag and started what was instantly dubbed the Jeans Revolution.

How do cheap workpants call people to the barricades? Maybe rugged self-reliance has its uses, whipping up the kind of courage that sends people into the streets to fight for justice. New York Times fashion director Vanessa Friedman calls jeans “the great equalizer, unisex and uniclass, acceptable almost anywhere. And that, as a value system, is very American.”

No longer did we wait breathlessly, the way the first immigrants did, to copy the latest fashions from Europe. Instead, we put on jeans, and their casual, egalitarian impatience—with tyranny, aristocracy, excess wealth, outworn authority, stuffy rules, and every ism that oppresses—proved contagious.

I like that we chose such plain, tough garb as our icon. No longer did we wait breathlessly, the way the first immigrants did, to copy the latest fashions from Europe. Instead, we put on jeans, and their casual, egalitarian impatience—with tyranny, aristocracy, excess wealth, outworn authority, stuffy rules, and every ism that oppresses—proved contagious.

In a 2019 article not quite grieving “The Death of Denim,” Vice UK acknowledges that blue jeans’ iconic fabric clothed every cultural movement for more than a century, adding, “This is why it’s notable it’s no longer at the top of the menu.” Male readers are urged to “grab some peach coloured jogging bottoms.”

Will peach joggers carry the same energy?

rag & bone

In the Seventies, when it was still your job to break in your blue jeans, you could cheat by wearing black or white or khaki jeans, but indigo was their true color. An extraordinary plant dye, it knew how to create suspense, first turning the thread yellow-green, then reacting to oxygen and magicking into that saturated dark blue we tried so hard to fade.

The invention of synthetic indigo was such a big deal, it won a German chemist a Nobel Prize in 1905. But when another chemist worked overtime to perfect a nonfading indigo, he was told, “You’ve just invented something nobody wants.”

The transformation was the point.

Now that jeans were signed by designers with distinct personalities, not just certified as Levi’s-tough, they had to change dramatically every season, stoking demand and jacking up prices. Armani put forth a “smoky wash,” “ice-blue wash,” and “tea wash.”

In the Eighties, manufacturers took over that transformation, authenticating our jeans for us. They bleached, shrank, and stonewashed for us, assembling jeans that look lived-in before they ever touched our skin. Fashion designers dove in, stealing blue jeans’ symbolism and playing with the iconography. Soon they had turned what was tough and affordable into something bedazzled, sleek, or high-concept trashy, precious in the worst sense of the word.

The variations were one more example of American inventiveness. Or attention deficit. We were bored with basic jeans and tired of doing the work ourselves, and our hungry consumer economy needed us to buy not one pair of jeans but seven, not when they wore out but every season. By 1991, a boutique group was pasting up billboards in New York: “Ripped Jeans, Pocket Tees, Back to Basics, Wake us when it’s over. Charivari.”

The joke was on them. Jeans continued their ascendancy; it was Charivari that was over.

The tale—again, so American—will break your heart. Now that jeans were signed by designers with distinct personalities, not just certified as Levi’s-tough, they had to change dramatically every season, stoking demand and jacking up prices. Armani put forth a “smoky wash,” “ice-blue wash,” and “tea wash.” In 1996, Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger jousted in a “war of jeans.” (Tommy won.) Good ol’ Levi’s were left in the dust.

Lucky Brand

Plaster was crumbling, wiring was exposed, and there was a furnace in the changing room at Rathert Clothing, a dusty but venerable little store in Red Bud, Illinois. Family-owned, it had opened the same year blue jeans won their patent. Yet in 1997, Levi Strauss & Co. informed Don Rathert that his store did not meet their standards; they were seeking “high-image retail customers.”

“We’re not real modern,” the assistant manager at Rathert conceded, “but we always pay our bills.” Word spread that Levi’s had canceled ninety percent of Rathert’s business, which focused on selling jeans as cheaply as possible. National news outlets picked up the story, and outraged customers fired off letters. All this talk of image felt downright un-American. “Where is your sense of loyalty?” U.S. Rep. Jerry Costello demanded of the Levi Strauss CEO.

The company reconsidered. As for its designer rivals, once Tommy, Ralph, and their pals gussied up blue jeans and sold them for three times the usual price, their appeal began to fade. Granted, Gucci managed to wring $3,700 a pair for jeans that were in far worse shape than the $1.46 originals. But on the rung below couture, the U.S. market was hollowing out.

America’s beloved must-have was fast becoming a caricature of itself. The jeans Yves Saint Laurent admired for their relaxed nonchalance, their “modesty, sex appeal, simplicity,” were now luxury denim, trimmed in mink or ripped to shreds or tighter than a wetsuit.

To recoup profit, jeans companies left the American South, where factories had run on cheap female labor, and moved overseas. Soon nearly every pair of jeans sold in this country was made outside its borders. Sweatshops exploited global workers as surely as jeans’ manufacturing process sucked up water, turned rivers blue, and spewed cyanide and formaldehyde into the groundwater. Each pair shed about 56,000 microfibers per washing, and those blue filaments now stain the Arctic oceans.

There was something deeply scornful about persuading young women to save up their clerical paychecks and hand over vast sums for the sort of pants worn by street repair crews. Especially when other young women were coughing blue dust in a factory in Bangladesh as they drilled artificial holes in those pants for less than a dollar. But few of us worried about any of that when we stepped into our jeans on Casual Friday. Who would return willingly to Mr. Strauss’s rough, dark denim? It was far nicer to have somebody else fade our jeans in a washhouse halfway around the world than to stone and beat them into submission ourselves.

The new millennium brought skinny jeans that fit like skin and rode so low, they only worked for anorexic celebrities. “Jeans too tight, too skinny for me; the size is right but it doesn’t fit me,” even the lithe young sisters of Rubi would sing years later. At the time, I glared at the dressing-room mirror, my thighs blue-cased sausages tied off at the knee, and decided this was not shopping, it was a mortification of the flesh. And there was no way I was handing 7 for All Mankind $180 as my penance.

America’s beloved must-have was fast becoming a caricature of itself. The jeans Yves Saint Laurent admired for their relaxed nonchalance, their “modesty, sex appeal, simplicity,” were now luxury denim, trimmed in mink or ripped to shreds or tighter than a wetsuit.

The way was paved for athleisure.

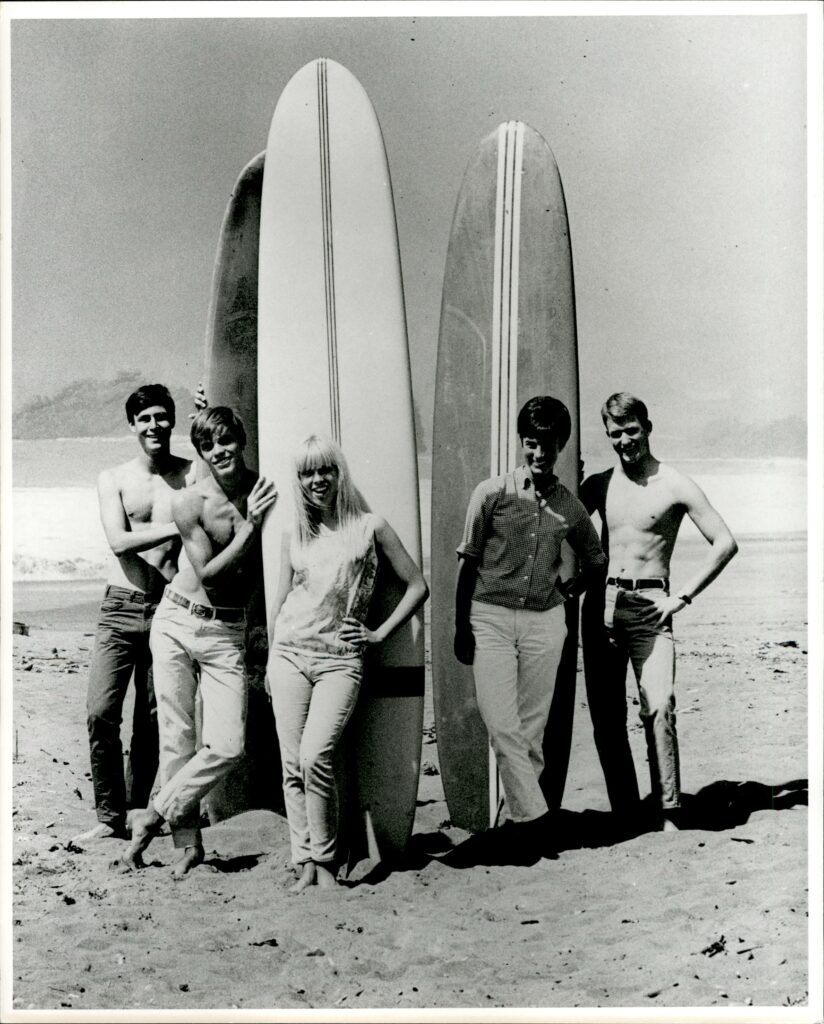

Advertisement for “White Levi’s® Guys + Gals c. 1960s. Levi Strauss & Co. Archives. (Courtesy Contemporary Jewish Museum)

American Eagle

At Jana Prikryl’s naturalization ceremony, she was startled to hear the federal clerk announce that this was a dignified occasion, and anyone in blue jeans should go home and change. Prikryl, who came here as a refugee years earlier, still remembered the emotional high she felt buying her first pair: “Those jeans cemented my sense of belonging.” Surely, she thought, “if any item of clothing constitutes the national costume of the North American animal, it’s jeans.”

She wrote this for The New York Times, echoing Georgia O’Keefe, who wore Levi’s and chambray shirts to paint the desert and called blue jeans “the costume of this country.”

The fact that our costume began as a sturdy and predictable garment, then evolved into a million variations and constant novelty—how American is that?

How American, too, that they spell freedom so many ways. My mom once suggested we wear jeans to the symphony. I slunk in behind her, missing my velvet decorum, but she (raised with too many rules) relished every minute. Jeans were a fuck-you to the nuns who made her youth miserable.

How American, again, that jeans were invented by an immigrant—who was born Loeb Strauss, so if he had not reinvented himself, we would all be wearing Loeb’s—and inspired by foreign textiles. And became a national symbol. And lit an international craze.

After World War II, the Japanese took the scraps of discarded American jeans and carefully stitched them together again. During the Cold War, an $8 pair of blue jeans, sold behind the Iron Curtain, brought at least $90 on the black market. Italians, introduced to jeans as military surplus, decided they preferred them sleekly tailored in velvet, corduroy, and gabardine. When Georges Pompidou was president of France, he ordered a pair in leather. In Turkey, they were dubbed blucin, a phonetic transposition of blue jeans. By 1997, they had overtaken Mao jackets in Beijing.

When Kedron Thomas, an anthropologist on Washington University’s faculty, did field work in Guatemala in 2012, she found the contemporary Mayan community dressed not in Guatemala’s brilliant handwoven textiles but in faded blue jeans. Knockoffs, she realized, with fake Diesel or Levi’s labels. The world was that hungry.

Naked & Famous

Invited to some social event, the first question we used to ask was “Jeans okay?” A frown of hesitation or emphatic yes spoke volumes about what to expect: our parents’ world or our own. We had seen their girdles and pantyhose, ties and trousers. We were breaking free.

Put somebody in a pair of jeans, and they will carry themselves a little looser, sit on the floor more readily, roughhouse with a friend’s dog, meet celebrities and janitors with the same ease. The Saturday Evening Post was thrilled to report that England’s Princess Anne wore jeans while having her hair done the morning of her wedding, and photographers could not stop snapping when Princess Diana wore jeans (or slyly noting that the Queen did not). Seeing someone famous in a pair of jeans warms you to them (politicians know this). Silicon Valley’s prodigies made jeans a symbolic choice.

Jimmy Carter was the first [president] regularly seen in blue jeans, quietly underscoring his rural roots and outsider status. Ronald Reagan wore them as a California rancher would; George W. Bush as a Texas rancher would. Bill Clinton’s jeans were friendly, saggy, and southern; Obama’s were high-waisted dad jeans, though he looks a lot sharper these days. Donald Trump makes it a point not to wear blue jeans.

Even debonair Cary Grant ordered himself custom Levi’s for weekend wear. The Beatles came here in black suits and left in blue jeans and T-shirts. Andy Warhol, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, Patti Smith—can you imagine any of them performing in sweats or khakis? Madonna chose cut-off jean shorts for her Girlie Show Tour; Rihanna wears denim head to toe; Kanye wore jeans to the Met Gala.

And our presidents? Jimmy Carter was the first regularly seen in blue jeans, quietly underscoring his rural roots and outsider status. Ronald Reagan wore them as a California rancher would; George W. Bush as a Texas rancher would. Bill Clinton’s jeans were friendly, saggy, and southern; Obama’s were high-waisted dad jeans, though he looks a lot sharper these days.

Donald Trump makes it a point not to wear blue jeans.

B.U.M.

With the arrival of vaqueros (meaning cowboy, meaning American jeans), young working-class men in Buenos Aires said they felt like “a new person,” writes Valeria Manzano in “The Blue Jean Generation: Youth, Gender, and Sexuality in Buenos Aires.” Instead of trooping along with their fathers to a suit store in a stultifying rite of passage, they could show off young, virile bodies hungry for fun. Gay men were drawn to the same Marlon Brando look, their tight jeans and white shirts proudly body-conscious. Young women traded demure full skirts for jeans, shifting erotic attention from above their waist to below. As they displayed more of their bodies, they began dieting, eager to fit the new ideal of beauty. Jeans ads focused “on the overt display of young women’s buttocks.” Soon the mayor of Buenos Aires, joined by other civic leaders and psychiatrists, was fretting about the “over-sexualization” of public life and, at the same time, the danger that unisex fashion would blur gender roles.

Everything they were afraid of was already happening in the States. Nothing, murmured the precociously sensual Brooke Shields in 1980, “comes between me and my Calvins.” In classic Madison Avenue sleight of hand, viewers’ minds raced to what she was not wearing. More than 2.5 million pair of Calvin Klein jeans were sold the month that commercial aired. “Jeans are sex,” Klein explained with a shrug. “The tighter they are, the better they sell.”

Like this nation we once called a melting pot, jeans both affirm and cancel identity. Wear them as you travel the world, and no one will know where you came from.

Close your eyes and conjure your favorite pair, the fabric worn lighter at the seams and bends, the legs whiskered with pale creases that tell the world how you cross your legs or kneel or shift your weight. In their own brusque way, jeans are as intimate as lingerie. Yet they are also hypermasculine, conjuring old-growth forests and wild mustangs and guys who can build and fix things. What a thrill a woman in the Forties must have felt, shucking off a long, narrow skirt, unrolling silk stockings, wriggling out of a girdle, and stepping into a pair of jeans. Lengthening her stride, moving freely, bending unselfconsciously. Running, even, her curls unstuck and windblown. Maybe she wore her jeans to a new job in an assembly line, making more jeans. Their production had been declared an essential wartime industry.

For women, jeans promised less fuss; less exposure; less prescribed, gendered role-play. In a skirt, one must sit a certain way. In Dressed: A Philosophy of Clothes, Shahidha Bari writes, “Some of us prefer, instead, to reach more routinely for our jeans, a uniform, something unisex or unsexed altogether, in order to feel less at odds with the bodies we have and the world in which we are compelled to be.”

Yet there are few male garments I find as sexy as a guy’s jeans, worn and faded in significant places. And there are few female garments, I am told, that are as sexy as snug, low-rise jeans. A single pair of pants that spells maleness and femaleness, eros and androgyny, uniformity and individuality all at once—how American is that?

Like this nation we once called a melting pot, jeans both affirm and cancel identity. Wear them as you travel the world, and no one will know where you came from. Because they are ubiquitous, they reveal little about us, even as they take on the shape of our body. If we are honest, a $300 pair of faded, ripped “boyfriend jeans” is pretty darned hard to distinguish, at a social distance, from a $30 pair. Irreverent still, jeans refuse to categorize us.

They also refuse to be prim or formal. We grin when people try to freeze their jeans clean, or when Chip Bergh, the current CEO of Levi Strauss & Co., confides that he has not washed his jeans in ten years and urges the rest of us to stop washing ours. We love jeans for their grime, their rips and holes and faded color proof that we have spent time outside, done things, used our bodies, touched the earth. Jeans gather trace evidence of every experience we have.

Reformation

There was a time we loved our jeans so much, engineers did studies to determine the exact color of light that would show them off in a mall store.

Now malls are dying, and in 2017, Cone Mills’ White Oak plant in Greensboro, North Carolina—which once made nearly all the denim for Levi’s 501®s—closed its doors. It was the last place in the country to weave selvedge denim, and it used midcentury shuttle looms, the weft yarn gliding back and forth across the loom to keep the weave tight and textured. Wearers showed off that edge, which would never unravel, by flipping up a cuff.

Today, the most authentic Levi’s are made in Japan, where artisans spoon-feed wheat bran to vats of naturally fermented indigo (not the chemical stuff) and keep it warm over heat lamps. Real indigo must be kept alive, like a pet creature. “If the indigo is happy today,” they say, “we can dye maybe fifteen pair of jeans.”

(Courtesy of the artist, Ian Berry)

When he learned of the plant’s closure, Michael Williams, founder of the menswear site A Continuous Lean, sighed heavily. “Americans have lost yet another piece of our national identity.” The last fabric milled at White Oak became part of Secret Garden, an all-denim contemporary art installation. By a British artist.

What happened? The world thought we were cool, and we decided to make a monstrous profit. We moved manufacturing overseas. And then the world fooled us and stole the manufacturing and sold us back our jeans. In 2018, Europe led the global jeans market with more than thirty percent of revenue, and Asia Pacific led in terms of volume, with more than forty percent of the market share worldwide. They are still the global go-to, these American jeans, but we have betrayed their ethos.

Today, the most authentic Levi’s are made in Japan, where artisans spoon-feed wheat bran to vats of naturally fermented indigo (not the chemical stuff) and keep it warm over heat lamps. Real indigo must be kept alive, like a pet creature. “If the indigo is happy today,” they say, “we can dye maybe fifteen pair of jeans.”

In Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, cultural historian W. David Marx documents the irony. The word ametora means “American traditional,” as preserved by boutiques in Tokyo. They use antique U.S. looms, stitch on old sewing machines, then tap the crease into reverent precision with a wood-handled hammer, the date of purchase seared onto a leather patch. The Japanese are honoring what we once were.

True Religion

“You’re soft,” teases my mother-in-law, raised on an Arkansas farm. My generation let machines rip our jeans for us, let computers magic up a pair of bespoke jeans that fit better than our own droopy skin. And now, just when we have a million variations to choose from—jeans washed in acid or enzymes or faded by ozone or nanobubbles, lasered or hammered or sandblasted or shotgun blasted, high-rise or low-ride, boot-cut or tapered or skinny or wide-leg—we have decided we prefer soft pants. Elasticized or drawstrung, fitting any shape, expecting nothing from us and showing nothing off.

This was not how the story was supposed to end. In early 2020, the U.S. jeans market looked like it might be emerging from its long decline. Bored by leggings, fashion writers were high on denim again. Sales were strong worldwide, and Statista research showed the global market growing as cities grew and white-collar jobs went casual. The market value for denim fabric, $90 billion in 2019, was expected to increase to $105 billion by 2023.

Then the coronavirus struck.

People stayed in their pajamas for months, and denim sales went into freefall. Levi’s revenue sank fast, and True Religion, Lucky Brand, G-Star RAW, and the parent company of Joe’s Jeans and Hudson Jeans all filed for bankruptcy. In August, Washington Post retail journalist Abha Bhattarai told NPR the move toward comfort was speeding up, with designer jeans hit the hardest.

On Thanksgiving 2020, when The New York Times published a list of what readers were thankful for, it included “no shame in elastic-waist pants” and “more homemade pasta, no more jeans.” The pandemic was dragging on, the whole country was in a mood, and for those able to retreat, it was a time of self-pity and self-care. Temporary, surely? Ah, but even before the pandemic, Diesel USA had filed for bankruptcy, H&M had closed its jeans brand Cheap Monday, and Trendstop was forecasting “a more varied and softer expression of style” for men.

Had jeans’ triumph seeded their defeat? Once it was acceptable for women to wear them too, the original machismo began to soften. Once grandparents decided they could keep wearing theirs, youth’s defiant claim lost its edge. As the world’s divergent cultures began to borrow one another’s stuff, there was less reason to delight in a shared, recognizable garment. Why not trade the symbol for personal comfort?

A confession: I have been reading for weeks about the history of blue jeans, loving what they represent, relieved by the strides toward environmental and social justice, rooting for them to succeed—and doing it all in sweatpants. The body must be soothed.

In my idealistic years, I wore jeans all the time. I wanted to be someone who swung herself easily onto the back of a horse, clean-limbed and strong, my cheeks rosy, my head as clear as the air. Wannabe. Is that what jeans have been since the Sixties?

And have we given up altogether?

If I spent my days doing hard, straightforward physical work, rustling cattle or chopping wood, I would still prefer stiff jeans. Sitting and worrying call for a cocoon. And we do far too much sitting and worrying these days, all the time branding and posting, ordering and acquiring. We are less useful to each other, I suspect, than our forebears were. No wonder we like our soft pants, shun even the exertion of a zipper, resist anything that takes our daily measure.

But what about the myth, the rough magic of a shared garment that teaches the world about freedom?

“I don’t think jeans are going to go away,” Friedman says firmly. “Blue jeans are the ultimate American garment. That myth is woven deep into this country—the great outdoors, the wild West, the open plains….” Besides, she adds hopefully, “Biden looks pretty good in jeans.”

We are less useful to each other, I suspect, than our forebears were. No wonder we like our soft pants, shun even the exertion of a zipper, resist anything that takes our daily measure. But what about the myth, the rough magic of a shared garment that teaches the world about freedom?

Revtown is now promising premium jeans with “the comfort of your favorite sweats” (I doubt it) and Levi’s is pushing loose, even baggy, jeans, heralding “a new denim cycle.” Technology is beginning to solve the environmental problems its earlier iterations created. Tinctorium has a way to make indigo dye without the usual toxic chemicals and water pollution. Nanobubbles can do the softening and tinting, cutting water use by ninety percent. Engineers are finding ways to recover cotton fibers from trashed blue jeans, irradiate them, and use them to strengthen polyester concrete. IKEA recycles them as slipcovers.

If we can halt and make amends for all the exploitation, maybe we can also recover the rugged work ethic, the democracy, the idealism. Maybe we can agree that our most iconic national garment should be affordable and sensible, straightforward, made with integrity. Softened up, sure, but could we at least rip them ourselves? Get outside, abandon mediated reality, chop some wood?

“Sweatpants,” Karl Lagerfeld once warned, “are a sign of defeat.”