“Not long after the transit strike began the other day, Mayor John V. Lindsay went on radio and television to announce that New York is a fun city. He certainly has a wonderful sense of humor. A little while later, Lindsay cheerfully walked four miles from his hotel room to City Hall, a gesture which proved that the fun city had a fun mayor.”

—Dick Schaap on newly elected New York City Mayor John Lindsay and the start of the 1966 NYC transit strike

“We’re the new faces for the new generation.”

—New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath celebrating the Jets victory in Super Bowl III (January 1969) with Mayor John Lindsay at NY City Hall

• • •

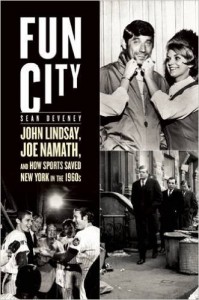

Sean Deveney’s book is about the intersection of the careers of two men, Joe Namath and John Lindsay, who had almost nothing to do with one another, and the city of New York at a crucial time in the history of sports, politics, and urban America. As Deveney writes, “New York in the 1960s would be a fast-evolving and nearly ungovernable city.” (Indeed, one of the major books about this era of NYC is the compulsively readable The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York by Vincent J. Cannato (2001), which has twice the political history of Deveney’s book, and none of the sports.) If race riots were to be the measuring rod, it would seem that by the late 1960s virtually every significant American city had become ungovernable but New York, being New York, was probably the most famous, the most prominent for unraveling at the seams in a maze and a haze of special interest, rough tactics politics: it was the age, to use Mayor Lindsay’s phrase, of “the power brokers.” In actual fact, unlike Newark or Detroit, it was not race riots that did NYC in, but virtually everything else that crippled cities in the 1960s: public employee union strikes, corrupt city planning, neglect of black ghettos, white resentment of growing black militancy and increasing political demands, excessive use of police force to deal with rising crime, decaying public schools, a fleeing white middle class.

But it was sports that “had long bound together the heterogeneous citizenry that made up the city,” and in the 1960s the NYC sports scene changed radically: in baseball, the Giants and Dodgers had departed for the West Coast; the Mets were added to the National League in 1962; the New York Jets née Titans of the upstart American Football League challenged the beleaguered New York Giants of the National Football League; and the New York Yankees, the perennial champions since the era of Babe Ruth, who had appeared in every World Series from 1960 through 1964, would fade from view and not be heard from again for the rest of the ’60s. But no single athlete made a bigger splash on the NYC sports scene or more powerfully reflected the change of the 1960s than Namath, the star quarterback of the New York Jets and the embodiment of the Playboy magazine swinger; here was the anti-establishment free spirit in the sport that represented, to that point, the button-down virtues of a masculine Cold War establishment, nurtured on the triumphalist politics of World War II. (Hugh Hefner’s Playboy would enjoy its greatest influence and popularity in the 1960s, as did Namath.) As Deveney writes, “In New York’s political milieu, Lindsay was a symbol: the White Urban Crusader. In New York’s social Milieu, Namath was a symbol: the Hedonist’s Quarterback.” The fate of these two men is, in essence, the story of this ironically yet un-ironically titled book.

John Lindsay (1921-2000) was the last great prince of reform-minded, East Coast WASP-dom, the last of the powerful northeast, big city liberal Republicans. A former Congressman from a well-off though not socially prominent or rich family, Yale-educated, blond, blue-eyed, ruggedly handsome at 6 feet 4 inches, Lindsay, like Barack Obama, who imitated aspects of Lindsay’s style (rolled-up sleeves, aspirational rhetoric, photogenic gestures for the less fortunate), seemed as if he were a politician who had just stepped out of central casting. One might imagine him walking through some restless ghetto or ethnic enclave on some stifling summer night, as Lindsay often did in his attempts at outreach or to calm unrest, to the late Glenn Frey’s “You Belong to the City.” If he was the beginning of the last gasp of liberal WASP power, he was, too, the first politician to associate himself with, to, in fact, become the face and voice for, the urban crisis.

As Deveney writes, “In New York’s political milieu, Lindsay was a symbol: the White Urban Crusader. In New York’s social Milieu, Namath was a symbol: the Hedonist’s Quarterback.” The fate of these two men is, in essence, the story of this ironically yet un-ironically titled book.

He succeeded longtime Democrat Mayor Robert Wagner, a typical welfare state, big city, machine politician who worked to keep the white ethnics, certain blacks, and the unions happy, the trains running on time, as it were, and who had no vision for the city but who knew which levers to pull to keep the city functioning. In this regard, Lindsay, with his outreach to black, Puerto Rican, and poor white communities, and with his appeal to civic grandeur, did seem “fresh,” as his campaign posters said, and everyone else did seem “tired.” Lindsay was the advocate for the rejuvenation, the moral reclamation of the neglected American city, that nightmare grid of corrupt, insensitive bureaucratic and administrative structures layered over the irrational improvisation of late capitalism that combined dazzling spectacle with unabashed yet grievous expressions of inequality. Lindsay, like earlier WASP liberal urban reform politicians such as Joe Clark and Richardson Dilworth in Philadelphia in the 1950s or contemporaneous ones like Carl Stokes, elected the first black mayor of Cleveland in 1967, or subsequent ones like Jane Byrne, elected first woman mayor of Chicago in 1979, had come to save the city, not to bury it. Lindsay did not save the city but he did not bury it either. There were times when he might have felt it had come close to burying him. It certainly buried his ambition to become president of the United States, something many of Lindsay’s fans and supporters thought he had been bred to become.

Joe Willie Namath (b. 1943) of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, like Stan Musial and Honus Wagner before him, escaped the fate of small-town working-class life by becoming a star athlete. Trained under the houndstooth hat-wearing autocrat Bear Bryant at the powerhouse football school, the University of Alabama, Namath was arguably the most sought-after player in the college draft of 1964. He became, arguably, the most famous American athlete of the 1960s. He vied for that distinction with heavyweight boxing champion Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali. There was no question that, during the 1960s, Namath was surely the highest paid American athlete, signing with the New York Jets of the upstart American Football League in 1965 for the astronomical sum of $427,000, a sure indication of how sought-after he was. (Incidentally, Namath, in addition to being drafted by the Jets of the AFL, was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals of the NFL. But it was commonly thought that the Cardinals had no intention of keeping Namath but of signing him than trading him to the New York Giants, who desperately wanted the brash quarterback.) The huge contract made Namath unpopular with his teammates, many of whom despised the upstart who got more press coverage than the rest of the team combined and who was a favorite of the ownership. Namath wore white shoes while playing, unheard of at that time (although the white shoes were not exactly his idea), hung out with movie stars, and generally enjoyed himself. Deveney writes, “Namath was dedicated to, in his words, ‘girls, clothes, and good times, and I don’t need more to enjoy myself.’” While many of Namath’s teammates did not like him, he was probably the single most important bridge holding the team together in the late 1960s because he was so comfortable, un-self-conscious, and authentically himself around black players. Namath was not a liberal trying to prove something. He did not seem to possess a political bone in his body. Namath was only interested in being himself and he felt fine being around blacks at a time when the racial divide was cleaving and deepening in American sports. So, while he was a distraction and an object of envy, he was also a unifying force for the Jets.

Namath’s bad right knee, surgically overhauled a few times by 1965, kept him from being drafted, which many people thought outrageous at the time. “Those who were incredulous that a quarterback like Namath couldn’t perform as a soldier were missing the point,” Deveney writes, “With that knee, it was a miracle he could perform as a football player.” (Emphasis original) (It should not necessarily be imputed that Namath’s deferment was racial and that a black player would not escaped the draft for that reason; in fact, Namath’s teammate, running back Emerson Boozer was also rejected by the military for a bad knee but went on to play football for several years. It should be recalled that baseball great Jackie Robinson was given a medical discharge by the army for a bad ankle, yet played Major League baseball for ten years.)

One might say that Lindsay’s first term as mayor could have been called the Education of John Lindsay. Upon immediately taking office, he had to deal with a transit strike where the Transport Workers Union chief bullied him and disparaged his incompetence and inexperience. Garbage and trash workers also decided to strike, bringing NYC to its knees under mountains of refuse. Lindsay endured three teachers’ strikes over the Ocean Hill-Brownsville experiment in local community school control which wound up pitting black parents and activists against Jewish teachers and union leaders in a standoff where the various parties were partly right in their stances, shameful in their racist utterances, and morally offended that they should be opposed. But Lindsay learned, and by the time of the Republican convention of 1968, where he offered the seconding speech for loathsome vice presidential nominee Maryland governor Spiro Agnew, Lindsay the reformer had learned to play the game of conventional, hard-ball politics triangulated against reform and protest politics, Lindsay also became the face and voice for NYC’s mass protests against the Vietnam War and for civil rights and racial justice as the driving force behind the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, popularly known as the Kerner Commission Report, which basically explained that urban riots were caused by structural racism and flagrant neglect of minority communities. In this way, Lindsay, being both Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside, astutely got himself re-elected, but he missed his moment to become president.

Deveney’s readable book has a happy climax, but actually both Namath and Lindsay were disappointments, neither being as great as he could have been. Namath never made it back to the Super Bowl. Lindsay, after switching parties in 1971, never became president.

As Lindsay headed toward reelection in 1968, Namath was guiding the Jets to the Super Bowl that same year. The two previous Super Bowls had been dominated by the NFL champion Green Bay Packers and most sports writers and the cognoscenti favored the powerful Baltimore Colts to beat the Jets easily. But with Namath boldly “guaranteeing” that the Jets would win, a toss-off phrase on his part that became a headline, the Jets stunned the sports world by winning the January 1969 game, 16-7, with brilliant play from Namath, who was named the game’s MVP. With this victory, the AFL had become legitimatized as an equal to the NFL, which was important for the competitive authenticity of pro football itself. In 1969, the New York Mets, who lost 120 games in 1962 when they entered the National League as an expansion team, would win the World Series behind the pitching of Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman and the hitting of Tommie Agee and Donn Clendenon against another potent and heavily favored team from Baltimore, the Orioles.

Deveney’s readable book has a happy climax, but actually both Namath and Lindsay were disappointments, neither being as great as he could have been. Namath never made it back to the Super Bowl. In fact, he never won another playoff game. Lindsay, after switching parties in 1971, never became president. In fact, after his second term, he was never to win another elective office. Deveney tells us a tale of missed chances, of rebels with a cause whose success adumbrated their larger failure in an ironic, but unmistakable, way. It is a story of those special ones who change their times, but never truly fulfill them. It is a story such as this that makes NYC appear so much, to those who do not live there, to be both a fun city and some comically-heroic, distant country.