“It is funny about money,” wrote Gertrude Stein, who thought money “a fascinating subject,” adding that it was “really the difference between men and animals,” and concluding, “everybody has to make up their mind if money is money or if money isn’t money and sooner or later they decide that money is money.” For Miss Stein the decision came later rather than sooner …

—from the essay “Money is Funny” in Joseph Epstein’s 1991 collection A Line Out for a Walk

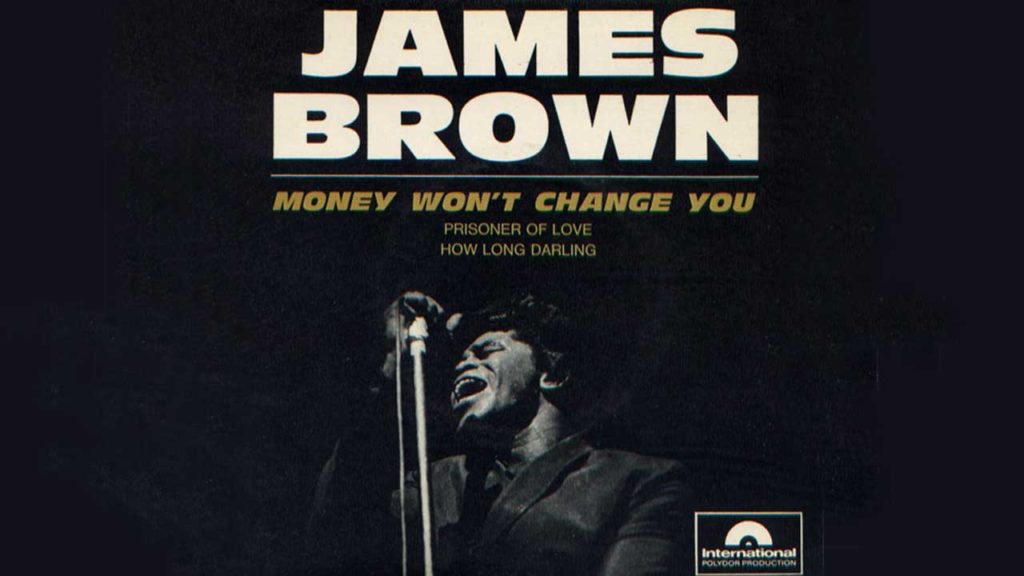

The title of this new themed issue of The Common Reader is from soul and funk singer James Brown’s tune of the same name. “Money Won’t Change You” was recorded in June 1966 and released in July of the same year. It reached Number 11 on the rhythm and blues chart and Number 53 on the pop charts, which means that it wound up being played more on black radio stations than on white or Top-40 pop stations. The fact that this two-sided single—“Money Won’t Change You” was 6-minutes long and was split into approximately 3-minute parts one and two on either side of its 45-rpm release—was not terribly successful in the white market did not reflect that Brown had not become a successful crossover artist by the time the tune was recorded. Earlier in 1966, “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” (with a string orchestra, no less) reached Number 8 on the pop charts; “I Got You (I Feel Good)” in 1965 reached Number 3; and “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” which Brown always considered the song that reinvented R&B music, reached Number 8 a bit earlier in 1965. But “Money Won’t Change You” seemed peculiarly coded as a song with a high black appeal.

“Money Won’t Change You” is considered one of Brown’s “message” songs—or what I call his “Black American Dream song cycle”—coming out as it did mere months before “Don’t Be a Dropout.” Brown had an enormous respect for education—as an uneducated man himself, he may have had more sincere regard for it than it truly merited—and constantly urged blacks to stay in school. He underwrote the education of several blacks during his life and had willed a significant portion of his estate to fund the educational aspirations of impoverished students. Brown made other “message songs” in his career: “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door and I’ll Get Myself)” (1969), “Funky President” (1974), “Get Up, Get Into It, and Get Involved” (1970), “King Heroin” (1972), “Mind Power” (1972), “America is My Home” (1967), and, of course, “Say It Loud-I’m Black and I’m Proud” (1968), among others.

It is hard to discern what message “Money Won’t Change You” is conveying because, first, half the lyrics are indecipherable, not unusual for a Brown song, particularly one of his fast-paced tune. This is largely a result of Brown’s black Southern accent and occasional screams, the strong probability that the lyrics were at least partly improvised, and that Brown—like guitarist Jimi Hendrix—intentionally sang portions of his songs so that they could not be understood in order to disguise the weakness or inadequacy of the lyrics. Black singers have been doing that sort of thing since the early days of blues and gospel, indeed, since the work songs of bondage days. It was the timbre and the expressive power of the voice that mattered. The full refrain of the song is often misinterpreted–check out the rendition of the lyrics online—as “Money won’t change you, but time will take you on.” Actually, it is “Money won’t change you but time will take you out.” (Aretha Franklin’s 1968 cover rendered the refrain, “Money won’t change you but time is taking you on.”)

What the song had going for it was a great title and a killer riff. In fact, the song is built basically around one riff with something like a bridge to keep it from getting monotonous. It was a dance tune, and I remember a lot of parties that my older sisters attended where folks “got down,” as it were, to “Money Won’t Change You” for its entire 6 minutes.

Second, the lyrics seem discontinuous; that is, they seem to defy conventional songwriting wisdom by not telling an obvious or clear story. It seems as if the song is about male/female relationships—a standard theme in R&B and indeed most of American popular music. But there are also lines about Brown’s dancing (“I don’t dance to suit myself/I dance to suit everybody else”), about doing the “mashed potatoes,” a popular teen dance of the time, “slow” and other “ad hoc” references that seem to muddle the message, so to speak, in a way that is counter to the clarity in virtually every other message song he ever made.

What the song had going for it was a great title. Readers might think from our cover image that Brown’s only point with the title was using “change” as a pun. But this was the furthest thing from Brown’s mind and “change” had no significance as a pun. Brown was not being comic with the title. The song also has a killer riff. In fact, the song is built basically around one riff with something like a bridge to keep it from getting monotonous. It was a dance tune, and I remember a lot of parties that my older sisters attended where folks “got down,” as it were, to “Money Won’t Change You” for its entire 6 minutes. Famed and fiery African-American poet/playwright/polemicist Amiri Baraka, thematized the song as part of the Black Arts Revolution in his 1966 essay, “The Changing Same (R&B and the New Black Music)”:

“If you play James Brown (say, “Money Won’t Change You … but time will take you out”) in a bank, the total environment is changed. Not only the sardonic comment of the lyrics, but the total emotional placement of the rhythm, instrumentation, and sound. An energy is released in the bank, a summoning of images that take the bank, and everyone in it, on a trip. That is, they visit another place. A place where Black People live.

“But dig, not only is it a place where Black People live, it is a place, in the spiritual precincts of its emotional telling, where Black People move in almost absolute openness and strength.”

If the song were played in a bank today (as it very well might be as times are, obviously, different now), I wonder what patrons would think. Better still, what would people standing in line to buy a Powerball ticket when the jackpot has exceeded $500 million think if they heard the song over the PA system in, say, a grocery store or at a gas station? “Half a billion dollars!” as someone in line said as we waited to buy tickets. A nice round sum to fantasize about as we all did, several of us laughingly confessing what we would do with such a windfall: all variations of the same theme, buy things and live better and give money to relatives and friends so they can buy things and live better. Would we have been deflated to have heard the song? Or would we have thought that Brown was surely not being serious? Would we have felt mocked or amused?

It seems counterintuitive to say that “money won’t change you,” when everyone believes, indeed, hopes that it will. That is the grand reason that everyone wants money: to be changed for the better, to have the life of one’s dreams. Did not Brown himself think that money changed him from the ragged, unloved boy of his Deep South days to one of the international icons of modern American music who, at the height of his fame, owned radio stations, private planes, palatial homes with a staff of valets, hair dressers, chefs, and chauffeurs? He was the black man of the late 1960s who symbolized a kind of Black Power, whose success, measured by hit records and huge audiences, by stopping a race rebellion in Boston with a televised concert, showed that blacks could make it in America, that capitalism could work for them as well as anyone. Brown reveled, at the height of his career, in being a capitalist and most of his black fans admired him for it. There was no greater Horatio Alger story of the moment than Brown. As he himself expressed it in “America is My Home,” “I’m sorry for the man/Who don’t love this land.” Loving capitalism was being an American. Despite the socialist rhetoric of most black scholars and intellectuals, scratch the masses of black people only slightly and beneath a socialist-sounding surface of equality is a subcutaneous core of capitalist desire. People, especially who have been downtrodden, do not really want equality; they want money because they crave the superiority and the freedom they imagine money will give them. Brown was in business of literally moving asses to a beat[1] and it might be said that capitalism, in which he staunchly believed, was about moving masses by moving asses even against their will or even their interest.

Money is a source of pleasure but not necessarily of fulfillment. In this sense, money “won’t change you” simply because it cannot do so, because money is not the completion of desire but the continuation of it. Money does not satisfy desire; it is only another remarkable expression of it.

“Money Won’t Change You” is a warning (part ironic, part cynical), not against having or acquiring money (most of his “Black American Dream Songs” praise having money), or against material possessions (most of these “message” songs adore having “stuff” as much as any current rap song); but rather a song that suggests the limitations of money, the mercenary world of money where people measure their feelings for you on the basis of whether you have it; the hard labor of getting it by pleasing others. Money is a source of pleasure but not necessarily of fulfillment. In this sense, money “won’t change you” simply because it cannot do so, because money is not the completion of desire but the continuation of it. Money does not satisfy desire; it is only another remarkable expression of it. Only time changes people, if only because it ages them and eventually “will take you out” because people cannot outlive it. Time is the only entity that can challenge desire and even exhaust it.

What is money? A medium of exchange that was an improvement over bartering as any children’s book on the history of money will tell you? The stuff that dreams are made of? The root of all evil? The source of all power? The thing that can buy anything but love? The thing that makes the world go ‘round? The one thing you cannot have enough of? The most important thing you cannot take with you when you die? The thing we hope most fervently will not disappoint us once we possess it in the way we want? Maybe money changed us a long time ago and there is really nothing it can do for us now as it is, in the human mind, both everything and nothing. “Money Won’t Change You,” the title itself, seems like the gimlet-eyed, flinty observation of a world-weary blues musician. But Brown was not a blues fan or a blues musician.[2] He was a revivalist, a different breed of performer.

If I am at least partly right about what the song is, then “Money Won’t Change You” may be one of the most telling, most unusually expressive songs ever written about money.