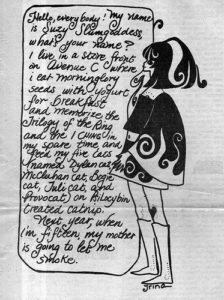

In 1966, while strolling in the Lower East Side buzzed on acid, Trina Robbins stumbled into the office of the East Village Other, one of the famous counter-cultural newspapers of the day. She was grateful to have a refuge to come down from what was a bad trip. To show her appreciation, she drew a single-panel cartoon with a huge word bubble featuring a character named Suzy Slumgoddess, inspired by a song by a group called the Fugs who at one time recorded on the same label—ESP Disks—as the legendary jazz bandleader Sun Ra. The cartoon was published in the next issue of EVO and this was the start, as Robbins puts it, of “her so-called career.” (10) More than that, it was not simply the start of an individual career, it was the launch of a movement of women cartoonists. To be sure, women had drawn comics and cartoons before the 1960s, Robbins, indeed, has become a major chronicler of these artists, but Robbins became a key figure in the women qua political women uprising, women as self-consciously seeing themselves as gendered creators of self-consciously gendered comics.

Robbins found the vein of girl-oriented comic stories and comic art that not only made her a fan of the genre but also interested her in how they were created and who created them. If only superhero comics were available, she would never have become fascinated with the genre in the way she did because she loathed such comics.

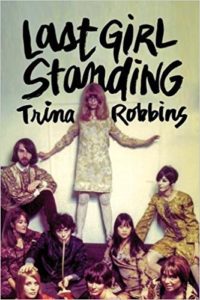

Last Girl Standing, the autobiography of cartoonist and comic book historian Trina Robbins, tells the story of a New York Jewish girl “who didn’t grow up in a dysfunctional family,” (14) whose mother was a second grade teacher and whose father was a tailor, loving parents but not particularly successful people. She describes herself as “a red diaper baby,” although neither of her parents belonged to the Communist Party. (18) She never became a political radical in the conventional sense, although she seems to have known some of them like Abbie Hoffman with whom she had “a fling.” (97) She said she knew no other politics “besides progressive Democrats and communists.” She has never heard of the IRA, for instance. (29) She tended to be more attracted to countercultural writers like Paul Krassner and Walter Bowart (97) and musicians like Jim Morrison of the Doors (61-62). Indeed, her teen ambition was not to be a communist revolutionary or an anarchist but rather “a bohemian.” (31) “I took French in high school so that I could go live in a garret in Paris and wear berets and become a great artist. I had not yet noticed that all the art I saw in Museums was by men.” (31)

Robbins’s first “proto-comic” of Suzy Slumgoddess, published 1966: “Thus began my so-called career.”

Two reading habits from her childhood and adolescent led to this aspiration: first, reading comic books and, second, reading science fiction. “I bought all the comics that featured girls or women on the cover: teen titles like Patsy Walker, Millie the Model, Katy Keene. … Along with Patsy Walker and Millie the Model, [Timely, later Marvel Comics] put out a seemingly unlimited supply of teen comics, mostly with girls’ names, and I bought them all: Junior Miss, Miss America, Nellie the Nurse, Tessie the Typist, Cindy, Jeanie, and Margie.” (21) Comic book reading is largely considered a boy domain, especially because of the dominance of superhero comics with characters like Superman, Batman, and the like. Even comic book heroines like Wonder Woman, Phantom Lady, Senorita Rio, Miss Victory (a superhero crimefighter during WWII), the Black Cat, Miss America (a superhero crime fighter during WWII, gifted with powers from the Statue of Liberty), the Woman in Red (a crimefighter who fought in a mask and gown), Sheena the Jungle Girl, Rulah, Skygirl, Batgirl, Mary Marvel, Supergirl, and Cave Girl (another jungle girl, a female Tarzan, of whom there were many), to name just a few, many drawn with in a sexy “good girl art” style meant to attract more boys than girls, indeed, marketed to boys. But there was a considerable number of girls who read comics, not only the ones mentioned by Robbins but an endless stream of romance titles about finding true love such as Young Romance, My Confession, My Experience, My Secret Story, Sweetheart Diary, True Tales of Romance, Thrilling Romance, Young Love, Heart Throbs, Hi-School Romance, Romantic Adventures, and True-to-Life Romance. Archie comics, about the adventures of a group of teenagers in a small town called Riverdale featuring Archie, his girlfriends Betty and Veronica, his best friend Jughead, and his rival Reggie were very popular with girl readers. And there were comic books like Little Lulu, Little Audrey, Wendy the Good Witch, and Little Lotta that appealed to younger girls as well. In short, Robbins found the vein of girl-oriented comic stories and comic art that not only made her a fan of the genre but also interested her in how they were created and who created them. If only superhero comics were available, she would never have become fascinated with the genre in the way she did because she loathed such comics. (21) In the 1960s, she would be inspired by the new trend in superhero comics such as the Fantastic Four, X-Men, and Dr. Strange, figures that were part of how Marvel redefined and updated the genre. (56) The kitschy, campy, pop art satire Batman, starring Adam West, that ran on ABC from 1966 to 1968, greatly affected the transformation of comics from children to adults, recasting how superheroes could be dramatized, indeed, extending their reach among the public as icons. Hippies, like Robbins, was taken by the wacky nature of the show, intensified by watching it while high on drugs.

Science fiction is also considered a largely male domain. Robbins was surely attracted to the genre in part because of the intricate art connection between comic books and the pulp magazines she began to read as a teenager. But she seemed a kid who lived in her imagination, who sought creative outlets in her head. She started to sci-fi conventions, making costumes for herself for these occasions, hanging out with other kids who liked pulp art and thus formed the platform for her creative self with the beginnings of this supportive, like-minded community. At 16 years old, she even dated future sci-fi legend Harlan Ellison. (36)

Robbins’s comic ode to sibling rivalry and adoration: “Big Sister little sister.”

Influenced by her father, Robbins began to make clothes for other people, thus launching her career as a counter-culture fashion designer and boutique owner. From the geek crowd of comic books and science fiction, coffee house folk music and avant-gardism, she migrated easily to the world of hippies: free love (not so free for women, as she discovered), peace, drugs, and communes. The designing began in Los Angeles for performers like Donovan, Mama Cass, and David Crosby. When she returned to New York, she started the boutique. After closing the boutique, she became deeply involved in the underground comix movement, counter-culture cartoonists whose art and story broke all taboos, challenged all conventions, and rebelled against all restrictions of the bourgeois comic art world. (The comic book industry had highly regulated itself since the 1954 Senate investigation of comics and the 1954 publication of Fredric Wertham’s scathing attack on the art form, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth.) The result was startling innovation blended with pornographic male fantasies and outright misogyny. The principal artist of this new movement was Robert Crumb, who Robbins not only knew well but apparently set up with another woman while Crumb was married. (110) Underground comix, sold mostly in head shops and hippie boutiques rather than comic book stores, was largely the domain of men, as were standard bourgeois comics ranging from Mad magazine to The Amazing Spiderman.

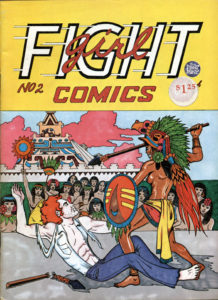

Robbins, at this point, mixed her growing feminist consciousness with her love of and creative engagement with comics, to launch an underground movement within the underground comix movement: feminist comix. She started by doing such single issues one-offs such as It Ain’t Me, Babe (a very famous title now) and the short-lived series Girl Fight Comics, whose covers mimicked those of the famous Fiction House title, Fight Comics. Eventually, Robbins’s leadership produced Wimmen’s Comix in 1972, not the first underground women’s comic series featuring women cartoonists but arguably the most famous. Tits and Clits beat Wimmen’s Comix to the stands by two weeks. The title was meant to be a sarcastic comment on how male underground cartoonists conceived their female drawings. (Olin Library’s Special Collection has the complete run of Wimmen’s Comix as well as many copies from the Tits and Clits series, Girl Fight Comics, and It Ain’t Me, Babe.) Wimmen’s Comix lasted until 1992, a longer run than Tits and Clits.

A comic cover of Robbins’s “boom time” work: “When you draw comics, anything is grist for the mill,” she writes.

Last Girl Standing is a highly enjoyable, honest, funny, at times, poignant autobiography. It has its share of score-settling or, as I suppose Robbins would see it, record correcting. As both a writer and artist, she is clearly a pioneer in the field of comic art, a historical figure of some real importance in popular culture and feminism, and in many respects an admirable person or at least a person that would not mind knowing. The book is highly recommended.