Ask a serious cinephile to name the most significant year in the history of film, and a literal-minded individual will sometimes cite 1895. That was the year that filmmaking pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière projected their moving images for a ticketed Parisian audience—giving birth to commercial cinema as it is still understood today. Pressure a cineaste to specify the most significant year in the development of film—rather than its arguable origin—and they are likely to name 1927. In that year, The Jazz Singer arrived as the first feature-length motion picture with synchronized music and speech, an event that initiated the relatively swift end of the Silent Era.

These watersheds, while obviously noteworthy for their long-term impact on the medium, are proximally moments of technological innovation. If one were obliged to select the most culturally momentous year in the history of film—at least English-language film—a strong contender would be 1968. That year saw the release of four epochal features that would dramatically re-write the rules of commercial cinema, either immediately or in hindsight: Planet of the Apes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Rosemary’s Baby, and Night of the Living Dead.

Much of the impact generated by these films was related to genre. In particular, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby established the “high art” potential of science-fiction and horror, respectively. These features illustrated that an internationally esteemed auteur could elevate categories that had for two or three decades been the domain of Saturday matinee fare aimed at undiscerning youngsters. Given its philosophical ambitions, cutting-edge visual effects, deliberate pace, and sparse dialog, 2001 was the furthest thing from a typical sci-fi B-picture. Likewise, Rosemary’s Baby was self-evidently no campy gothic thriller: Its otherwise garish Satanic cult premise was lent haunting sophistication by its incisive screenplay, deft performances, and sociological intricacy.

If one were obliged to select the most culturally momentous year in the history of film—at least English-language film—a strong contender would be 1968. That year saw the release of four epochal features that would dramatically re-write the rules of commercial cinema, either immediately or in hindsight: Planet of the Apes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Rosemary’s Baby, and Night of the Living Dead.

These were, unmistakably, films for “grown-ups.” Franklin J. Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes, meanwhile, was a more conventionally adventure-oriented spectacle, broadly accessible to both the young and old viewers who helped turn the feature into a hit. However, the dramatic sobriety with which the film approached its superficially goofy conceit—not to mention its tremendously bleak concluding twist—established that thoughtful, invigorating science-fiction could generate mainstream box office success. Indeed, all four of the aforementioned features were among the ten films with the highest domestic gross of 1968.

The truly surprising dark horse among this crop of films was, of course, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. An independent feature shot for a little over $100,000, the film quickly became notorious for its gruesomeness and proceeded to earn its budget back 250-fold, in the process spawning an entirely new subgenre of apocalyptic fiction. Notwithstanding the gut-punch of Apes’ desolate ending, Night of the Living Dead is arguably the most narratively and politically subversive work in this landmark quartet of films. Envisioning a world thrown into chaos by an undead insurrection, Living Dead tapped into ascendant fears of social upheaval, conceptualizing revolutionary movements as hysterical reactionaries might see them: an implacable, incomprehensible horde sustained by the worst atrocities imaginable. Yet as terrifying as the film’s cannibalistic ghouls can be, the real villains of the film are human panic, paranoia, and racism—the latter provoking a posse of good ol’ boys to gun down the African-American hero in the film’s shockingly pessimistic conclusion.

All four films cited above mirror, in some fashion, sentiments that were detectable in American life in the mid to late 1960s. It can be seen in 2001’s mingled conviction and skepticism regarding the arc of humanity’s future technological progress. It is discernable in Planet of the Apes’ certainty that our species is doomed to self-destruction, and in the film’s conception of a successor civilization that will inevitably repeat our worst mistakes. It can be observed in the suspicion with which Rosemary’s Baby regards “anyone over 30”—outwardly banal and old-fashioned, but secretly propping up a millennialist, Satanic conspiracy.

The notion that pop cinema can (intentionally or not) reflect the dynamics and subconscious rumblings of its present cultural moment with shrewd, evocative accuracy is nothing new. Indeed, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s was particularly flush with mainstream features that—whatever their actual setting—now seem like vivid if inevitably imperfect summations of the era’s mood, values, and anxieties. They encompass not only the four films previously mentioned, but also Bonnie & Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Five Easy Pieces (1970), and The Last Picture Show (1971), among others.

Most of these features were commercially successful and remain critically well-regarded, but their zeitgeist-mirroring import was necessarily fleeting—even as their deeper artistic merit endures. Constrained at least partly by the demands of profitability, mainstream filmmaking is generally more inclined to reflect the culture around it, rather than advance a new way of looking at the world. Despite its marquee director and prodigious budget, 2001: A Space Odyssey might be the only hit among this crop of features that still feels perpetually galvanic, perhaps because the pell-mell pace of technological innovation never slackens.

Even the films of 1968 that dared to be a little freakier were far more likely to echo the already-peaking psychedelic culture than to gaze into the future. Features like Barbarella, Head, Psych-Out, and Yellow Submarine (as well as 1967’s The Trip) are sometimes hailed for their trippy “vision,” but they are perhaps best described as “acid-sploitation” pictures. Such films are ultimately more interested in capturing and capitalizing on the hallucinogenic dimensions of the extant counterculture than in envisioning where it might all be leading. Even a feature like Psych-Out, with its skepticism towards hippie ideals and its bummer ending, feels more like grubby portraiture than a cutting-edge critique of the era’s myriad revolutions.

Films as diverse as The Devil Rides Out, Spider Baby, and Witchfinder General would end up looking faintly prophetic. In their roundabout, cock-eyed manner, these films each foresaw how “the wave would finally break and roll back”—as Hunter S. Thompson would memorably describe, some three years later, the end of the 1960s’ revolutionary spirit.

Ultimately, it was not the box office hits, the Oscar-winners, or even the overtly druggy cinematic curios of 1968 that had the clearest sense of where the Age of Aquarius might be heading. Rather, it was the smaller American and British horror features—most of them overlooked today—that seemed to discern the looming end of the Revolution. Films as diverse as The Devil Rides Out, Spider Baby, and Witchfinder General would end up looking faintly prophetic. In their roundabout, cock-eyed manner, these films each foresaw how “the wave would finally break and roll back”—as Hunter S. Thompson would memorably describe, some three years later, the end of the 1960s’ revolutionary spirit. Beneath the eccentricity, luridness, and grisliness of these films, one can sense the stirrings of the chaos and nihilism that would undergird later cinematic English-language milestones like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Taxi Driver (1976), Network (1976), and Apocalypse Now (1979).

Although it has largely been forgotten today, writer-director Jack Hill’s mind-bogglingly bizarre feature Spider Baby (alternately titled The Maddest Story Ever Told, Attack of the Liver Eaters, or Cannibal Orgy) is the 1968 film that most obviously bridges the considerable gap between the campiness of most horror cinema in the 1960s and the emergent nastiness of the 1970s. Indeed, Spider Baby resembles nothing so much as the malformed love child of The Addams Family television series (1964-1966) and The Texas Chains Massacre—with perhaps a dash of gleeful John Waters-style tastelessness.

Horror fixture Lon Chaney Jr. portrays Bruno, lonely caretaker and chauffeur to the degenerate Merrye family. Residing in a decrepit Victorian mansion, the three adult Merrye children—Virginia (Jill Banner), Elizabeth (Beverly Washburn), and Ralph (Sid Haig)—are all that remains of this unfortunate, inbred clan. All three suffer from “Merrye syndrome,” a purported genetic disorder that has afflicted the siblings with an arrested mental development and twisted, murderous compulsions. Bruno once swore an oath to the dying Merrye patriarch that he would protect the children from the outside world, but a crisis arises when distant cousins Emily (Carol Ohmart) and Peter (Quinn Redeker) appear with a smarmy, diminutive lawyer (Karl Schanzer) in tow. Green-eyed and clueless, the cousins have designs on the house, much to Bruno’s consternation. Unfortunately, the new arrivals agitate the children and provoke their homicidal appetites, leading to all manner of macabre, bloody, and quasi-incestuous ickiness.

Even by the freaky standards of 1968, Spider Baby is a profoundly perverse film, as much due to its tone as its content. Ostensibly a horror-comedy, it has a broad, kooky side that dabbles in grotesque satire and cartoonish mugging. Except for airhead legal assistant Ann (Mary Mitchel), the “straights” are all contemptuous buffoons, none more so than Schanzer’s attorney—a pompous, cigar-chomping twerp who improbably combines cynicism with obliviousness. At one point, he superciliously threatens litigation even as the giggling Merrye girls are hacking him to pieces with butcher knives, a mad satirical gesture that feels like some R-rated Hooterville fever dream.

Haig—who would later become a familiar face in exploitation features and on 1970s and 80s television—plays Ralph like a leering, gibbering toddler, and the result is significantly more unnerving than pitiable. Capering about like a coked-up chimpanzee in baffling costumes that switch between Little Lord Fauntleroy and Junior Samples, Ralph almost makes his bloodthirsty sisters seem lucid by comparison. (Eventually, Haig would come full circle, portraying the patriarch of a degenerate family in Rob Zombie’s House of 1,000 Corpses [2003] and The Devil’s Rejects [2005].) Any temptation to giggle at Ralph’s over-the-top antics is dashed by the time he sexually assaults Emily (off-screen, thankfully), who, it is implied, ultimately enjoys his brutish attentions.

This sort of jarring swerve is typical of Spider Baby’s tonal strangeness, which frequently finds the film juggling puerile silliness, Halloween camp, and stomach-churning unpleasantness in the same scene. It is unclear how the viewer is meant to regard a sequence where the good-natured but dull-witted Peter consents to being tied up by the arachnid-obsessed Virginia as part of a “the spider and the fly” game, only for his young cousin to then sexually proposition him and threaten him with erotic knife-play. Redeker’s strange decision to depict his character as a chuckling, embarrassed Dick Van Dyke only adds to the discombobulating oddness of the scene.

Untouched amid all this surreal dissonance is Cheney, who brings an earnest, gobsmacking pathos to the poor, miserable Bruno. The chauffeur regards his charges with tearful affection and a kind of paternal protectiveness, even as his despair mounts at concealing their bloody deeds from the authorities. He is perhaps the only character in this bizarre tale to garner even a modicum of sympathy from the audience, and even that is diminished by his after-the-fact complicity in the Merrye children’s crimes.

Although it has largely been forgotten today, writer-director Jack Hill’s mind-bogglingly bizarre feature Spider Baby (alternately titled The Maddest Story Ever Told, Attack of the Liver Eaters, or Cannibal Orgy) is the 1968 film that most obviously bridges the considerable gap between the campiness of most horror cinema in the 1960s and the emergent nastiness of the 1970s.

Similarly, the film’s ethos is hopelessly scrambled, albeit catholic in its jolly contempt for humanity. On the one hand, the film depicts young people—embodied and exaggerated in the Merryes—as depraved, infantilized monsters. In this respect, Spider Baby is a kind of horror-flavored update to the fear-mongering juvenile delinquency exploitation pictures of the 1950s (e.g., Teen-Age Crime Wave [1955]; The Violent Years [1956]). On the other hand, the film’s greedy, dimwitted adults are portrayed as richly deserving of their grisly fates, or (at best) damnably lucky to escape with their lives. No one comes out looking even vaguely admirable, except perhaps Bruno, who manages to reclaim his self-determination by the end—but only by blowing up himself, the children, and the Merrye house with a TNT suicide bomb.

Hill would go on to build a robust career in Blaxploitation and other niche genres throughout the 1970s, but even in a filmography that encompasses curiosities like Alien Terror (1971) and Isle of the Snake People (1971), Spider Baby stands out as a singularly peculiar work. It seems to queasily straddle the very broad gulf between crass comedy and pitch-black horror in a manner that has no real precedent in English-language cinema. Like an unstable nuclear reaction, this strange gestalt could only be maintained briefly. Four years later, in The Last House on the Left (1972), Wes Craven’s crypto-remake of The Virgin Spring (1960), the attempts at humor are relegated to a few awkward, vestigial scenes, while the violence is repugnantly sadistic in a manner that Hill would not have dared in 1968. By the mid to late 1970s, the balance in American indie horror tipped decisively into overpowering cruelty and desolation with the likes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977).

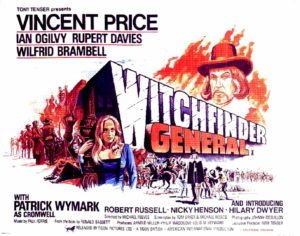

If Spider Baby was uncannily precise in its embodiment of the ongoing shift in English-language genre cinema in 1968, then director Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General was eerily prescient about the increasingly nihilistic direction of that shift. A co-production of British studio Tigon and American B-picture assembly-line American International Pictures (AIP), Witchfinder is as po-faced as Spider Baby is self-consciously goofy. Set in East Anglia in 1645, during the English Civil War, the film initially scans as a lush period drama, perhaps the low-rent version of a Franco Zeffirelli epic. (Including the obligatory, tastefully soft-focus love scene.)

The hero of this tale is Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy), a Roundhead soldier who is eager to marry his beloved, Sara (Hilary Dwyer), the niece of a well-heeled village priest (Rupert Davies). Unfortunately, said village runs afoul of Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), a self-appointed “witchfinder” who travels from settlement to settlement with his assistant, the ruthless torturer John Stearne (Robert Russell). Given license by the relative lawlessness of the war-torn English countryside, the pair take it upon themselves to identify, interrogate, and execute practitioners of witchcraft.

a well-heeled village priest (Rupert Davies). Unfortunately, said village runs afoul of Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), a self-appointed “witchfinder” who travels from settlement to settlement with his assistant, the ruthless torturer John Stearne (Robert Russell). Given license by the relative lawlessness of the war-torn English countryside, the pair take it upon themselves to identify, interrogate, and execute practitioners of witchcraft.

While Richard is away on maneuvers, Hopkins imprisons Sara and her uncle, subjecting the latter to gruesome trials allegedly intended to establish whether he is a servant of Satan. Initially, Sara acquiesces to Hopkins’ sexual coercions in exchange for leniency for the priest, but the witchfinder eventually executes her uncle and other villagers anyway. After Hopkins and Stearne have moved on to the next allegedly witch-plagued town, Richard returns to Sara and learns of the villains’ vile handiwork. He promptly sets out on a mission of righteous vengeance, his military obligations to the Parliamentarians be damned. What follows is a prolonged, halting chase as Richard pursues Hopkins and Stearne from one settlement to the next, perpetually a step or two behind the wicked pair.

From the vantage point of fifty years later, what is most remarkable about Witchfinder General is its unrelentingly dire tone. Once Hopkins and his flunkies descend on Sara’s village at the end of the first act, the film almost takes on the aspect of a vicious, revisionist Western—the late Renaissance equivalent of a Sergio Leone or Sam Peckinpah picture. Hopkins and Stearne make for an impeccably monstrous yin-and-yang: the former an eerily composed shade brimming with malevolent authority; the latter a crude, cunning beast who derives lip-smacking gratification from the infliction of pain. The tortures they perpetrate on the accused “witches”—drowning, burning, bloodletting, and other horrors—are presented with a chilly, unhurried matter-of-factness that somehow renders them even more appalling.

Squint a bit and one can see in Hopkins an eerie prefiguring of Charles Manson and his predatory exploitation of the political and social uncertainty of the 1960s. Amid the chaos of revolution, Hopkins cannily plays on the locals’ need for a stark morality in confused times, not to mention their dark craving for a violent outlet. Crucially, Witchfinder General is a wholly secular tale of terror: There is no actual black magic in this story, and it is strongly implied that local officials are simply pointing Hopkins at victims for their own petty, personal reasons. While Stearne appears to be a garden-variety sadist, Hopkins remains a black-hatted enigma, owing in part to Price’s imperious yet controlled performance. It is never entirely clear whether the witchfinder is a power-hungry cynic or a true believer engaged in his own demented inquisition.

Ultimately, the most disturbing aspect of Witchfinder General is how Hopkins’s sheer viciousness and apocalyptic worldview seem to infect everyone around him, including the film’s heroes. Over the course of the film, Richard becomes increasingly reckless and unhinged in his pursuit of the witchfinder, shirking his duties to the Roundhead army and leading his own men on an unauthorized manhunt. This sense of escalating madness and looming calamity comes to a harrowing climax in the film’s final scene, a sequence of astonishing brutality and darkness.

Ultimately, the most disturbing aspect of Witchfinder General is how Hopkins’s sheer viciousness and apocalyptic worldview seem to infect everyone around him, including the film’s heroes.

Richard corners Hopkins in a dungeon where Sara is being subjected to slow, shallow stabs with a dagger—an ostensible search for invisible “Devil’s marks.” In the ensuing scuffle, the soldier seizes a long-axe and proceeds to gruesomely hack the witchfinder to death, howling with rage. His own men beg Richard to stop this grisly business, to which the dazed soldier responds with hysterical shouts of “You took him from me!” As the Roundhead troops gape in horror, one of them intones, “God save us all,” and Sara begins to writhe and shriek uncontrollably. Her piercing screams continue, incessantly, as the film’s end credits roll. It is a shockingly ruinous ending—not bitterly ironic in the manner or Night of the Living Dead, but somehow just as disturbing. It feels unmistakably ahead-of-its-time, a sort of costume drama rehearsal for the nerve-frying conclusion of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or Captain Willard’s haunted stagger out of hell in Apocalypse Now. One is put in mind of what Thompson called the “bad craziness” that eventually cannibalized the idealism of the 1960s.

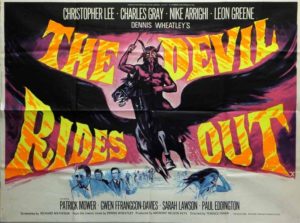

Superficially, director Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out appears to be a more straight-laced iteration of Rosemary’s Baby, in that both films concern a cabal of Satanic cultists working to reset civilization to a kind of malefic Year Zero. Whereas the latter feature is an arty European thriller at heart—its American setting and stars notwithstanding—Fisher’s film is presented in the mode of one of Hammer Films’ lurid gothic horror pictures. Indeed, British studio Hammer was one of the production companies behind The Devil Rides Out, and Hammer mainstay Christopher Lee stars as the film’s hero, the aristocratic occult detective Duc de Richleau. When considered alongside the American horror hits of 1968, Fisher’s film feels comparatively stuffy and tasteful, its stagey Technicolor sets and dignified campiness consistent with earlier Hammer landmarks such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958) (both of which also starred Lee and were also directed by the prolific Fisher).

However, the familiar Hammer tone that is evident in The Devil Rides Out conceals a story that is, in some ways, more tartly cynical than that of Rosemary’s Baby. Based on a 1934 novel by British author Dennis Wheatley, the script was adapted by no less a screenwriter than Richard Matheson, author of the seminal 1954 apocalyptic horror tale I Am Legend. (Matheson’s book was, funnily enough, a major inspiration for Night of the Living Dead.) The film is set in the South of England in 1929, which here resembles a kind of highborn Old World complement to the contemporaneous “weird New England” of American horror author H.P. Lovecraft.

However, the familiar Hammer tone that is evident in The Devil Rides Out conceals a story that is, in some ways, more tartly cynical than that of Rosemary’s Baby. Based on a 1934 novel by British author Dennis Wheatley, the script was adapted by no less a screenwriter than Richard Matheson, author of the seminal 1954 apocalyptic horror tale I Am Legend. (Matheson’s book was, funnily enough, a major inspiration for Night of the Living Dead.) The film is set in the South of England in 1929, which here resembles a kind of highborn Old World complement to the contemporaneous “weird New England” of American horror author H.P. Lovecraft.

De Richleau calls for his friend Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene) out of concern for Simon Aron (Patrick Mower), the son of a brother-in-arms who perished in the Great War. Simon has fallen in with a suspicious new circle of friends, and De Richleau—who, unbeknownst to Rex, is something of an occult scholar—quickly deduces that the young man’s wealthy, cosmopolitan companions are Devil-worshipping warlocks. (The giant pentagram on the floor of Simon’s new house is, as they say, a dead giveaway.) De Richleau and Rex manage to extract Simon and Tanith (Nike Arrighi), another young acolyte who has not yet received her unholy baptism, but their disruption of the Satanists’ sabbath only succeeds in drawing the ire of the cult and their high priest, the suave black magician Mocata (Charles Gray).

The Devil Rides Out generally follows the well-worn gothic B-picture model of the 1960s, a template perfected by Hammer and its stateside cousin, AIP. Today, pulp horror aficionados are more likely to admire Fisher’s film for its performances and novel setting than for the repetitive, back-and-forth plot or the dated visual effects. Lee is a characteristically striking presence in a rare heroic role, and the dapper Gray is unexpectedly menacing, particularly when he is working his mind control mojo on his victims.

What is truly distinctive about The Devil Rides Out in the context of 1968—and particularly in comparison to the much more artistically daring Rosemary’s Baby—is the subtly subversive nature of its story. The patrician interwar setting affords the film some obscuring distance from the Britain of the Swinging Sixties, but it is clear that the Satanist villains are the amoral libertines in the film’s conflict, while the forces of good like De Richleau are God-fearing traditionalists. This is not to say that Fisher’s feature is engaged in veiled hippie-bashing, or that it equates evil with the occult practices and New Age spiritualism that were a major component of the counterculture. (In fact, De Richleau’s facility with white magic is the only thing that saves him and his allies from Mocato’s sorcery on multiple occasions.)

Rather, The Devil Rides Out posits a sinister world in which the dissolute lifestyle associated with the counterculture—sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll—is the domain of a wealthy, autocratic, international cabal. The film’s Satanists partake of unholy libations, dance orgiastically, and revel in their carnal freedom, but when they start talking about a New World Order, they sound suspiciously like the Man. Their blasphemous revolution is little more than an oligarchic coup de ’tat, where the Christian establishment is swapped for a Luciferian one, and all the allegedly mind-freeing sensual pleasures of the 1960s are merely Satanic membership perks. In this, Fisher’s film seems to presage what historian Thomas Frank calls the “conquest of cool,” the process by which the cultural fruits of the era were colonized by capitalism and denuded of their revolutionary spark.

The Devil Rides Out posits a sinister world in which the dissolute lifestyle associated with the counterculture—sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll—is the domain of a wealthy, autocratic, international cabal. The film’s Satanists partake of unholy libations, dance orgiastically, and revel in their carnal freedom, but when they start talking about a New World Order, they sound suspiciously like the Man.

Rosemary’s Baby presents a conspiratorial evil that is slippery and unclassifiable: The film’s Satanists are Park Avenue geriatrics, at once hopelessly square, deviously sexist, and clandestinely hedonistic. (Intriguingly, the clearest voice of reason in the film comes from Rosemary’s young, female friends—modern, liberated ladies who straightaway see the Devil-worshippers for the creeps they are.) In comparison, Fisher’s film depicts a moral landscape that seems relatively stark and simplistic. De Richleau credits the heroes’ eventual victory to God, and the film largely seems to embrace the characters’ Manichean view of good and evil.

However, The Devil Rides Out is, in some sense, more pessimistic than Polanski’s feature. There is no obvious analog to the bohemian free spirits of 1960s counterculture in Fisher’s film. (The nearest equivalent in the feature’s 1920s setting would be the freethinking young men and women of the Lost Generation, who are unfortunately nowhere to be seen.) The film essentially depicts a struggle between Christian and secular English bluebloods on one side and multi-national Satanic aristocrats on the other. The Devil-worshippers are pointedly portrayed as more diverse, ethnically and gender-wise, but given that their leadership appears to consist entirely of princelings, duchesses, rajas, and chieftains, they plainly represent the commanding heights, not the revolutionary rabble.

In its oblique way, then, Fisher’s film presents a gloomy alternate history of the then-current social liberation, one in which the “newfound” hedonism of the 1960s was (surprise, hippies!) already claimed, colonized, and terraformed decades ago by monied, conspiratorial forces. In this respect, The Devil Rides Out, for all its Hammer horror fustiness, was culturally prescient in a way that no other genre film of 1968 would match. Its cynicism is so offhanded that it is almost invisible, but it proffers a grim certainty that the powers-that-be will always co-opt revolutionary ideals and use them for their own repressive ends. Within the lurid and narrow idiom of its Satanic conspiracy, Fisher’s film presents a dry, embryonic version of the critique that Thomas Pynchon would articulate so precisely decades later in his 1970-set stoner detective novel Inherent Vice:

Was it possible, that at every gathering—concert, peace rally, love-in, be-in, and freak-in, here, up north, back east, wherever—those dark crews had been busy all along, reclaiming the music, the resistance to power, the sexual desire from epic to every day, all they could sweep up, for the ancient forces of greed and fear?