A relative once told me about a childhood visit to the Du Quoin State Fair, in southern Illinois, in the 1950s. Once on the fairgrounds, his father bought them tickets to see the Wolf Boy act in the freak show, and they took seats in a hot tent with a few other people anxious to see what would happen next.

The Wolf Boy stalked out on the low stage, chained by the neck. He was a grown man, dirty, shoeless, stripped to the waist, with patches of fur glued to his face, neck, torso, and shins. He strained at his chains, gnashed his teeth, bounced on all fours, barked, and howled. At the climax, he bit the head off a live chicken and set the body loose in a fluttering of white wings. Just when things could not get any worse, the Wolf Boy jerked his restraints in a frenzy, got loose, and rushed the audience with his arms held wide to catch and eat them all.

People jumped off their seats and ran out the doors and under the hems of the tent, screaming and laughing. My relative, just a boy, ran too and stood among the rest of the crowd as they lit cigarettes and talked about what they wanted to see next. But his father had not come out, and he was alone. He thought the Wolf Boy must have eaten his father.

Still, he worked up the courage to go back in to look for him. His father and Wolf Boy were in the tent, talking and laughing together. They knew each other from fighting the Germans in North Africa.

• • •

The Du Quoin State Fair sideshow had not changed much a decade later, as Mark Kram showed in Sports Illustrated in 1965: “It is an odd time in town. Constant and subtle, a certain feeling pervades—a feeling of something kinetic and wonderfully foreign. […] The…fair, long ago described as a pagan outbreak, is hardly a disappearing rite of rural life [and one can still hear] the brag and bluster of the pitchmen. ‘See Mongo, the fattest man in all the world! See Margo, Margo, the untamed girl raised by a wolf pack! Folks, this man will amaze you by rubbing a burning torch over his anatomy! Girls, ladies and gentlemen, girls! Straight from the Copacabana in New Yawk!’ A handful of people gawk at the stage, their faces lined with sheepish grins. […]

“‘Friends, come right in,’ says the little hustler on the stage. ‘There’s nothing to be ashamed of, friends! There’s nothing finer in all the world than a pretty girl!’ The crowd is still small out front, and soon the show starts with only a dozen people. ‘Once,’ says an old man operating a game near the stage, ‘there were suckers around as far as the eye could see, but now the only suckers are us people still looking for the suckers.’”

By the time I worked the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, Illinois, in the late 1970s, there was still a barker (often called a “professor”), a three-breasted woman on display, a contortionist, fire eater, et al, but due to costs and regulations, sideshows were smaller, less graphic, and had begun to go the way of the circus “museum”—taxidermied animals, mannequins, and signage.

Attitudes on acceptable public entertainments, especially those endorsed by the state, were changing. Displays of nudity or of stillborn or aborted fetuses in jars would not last much longer. The performative killing of animals by “wild men” (and a few women) had mostly ended (clearing the way for the meaning of “geek” to change to its present use, of “narrowly-focused enthusiast”).

By the time I worked the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, Illinois, in the late 1970s, there was still a barker (often called a “professor”), a three-breasted woman on display, a contortionist, fire eater, et al, but due to costs and regulations, sideshows were smaller, less graphic, and had begun to go the way of the circus “museum”—taxidermied animals, mannequins, and signage.

Freak shows became few, “as physical anomalies were increasingly viewed from a medical standpoint and, later, as the beginnings of ‘political correctness’ took hold,” Brigham A. Fordham writes in the UCLA Entertainment Law Review. Fordham looks at laws meant to prohibit freak shows on the bases of exploitation, propriety, and discrimination, as well as First Amendment and other challenges to those laws, and he notes the “renaissance” of the freak show in the 1990s.

“Today [2007], the traditions, images, and fictions of earlier freak shows are increasingly reborn in traveling shows, displayed on internet websites, and morphed into television shows and performance art,” he says.

In the way that burlesque, roller derbies, and tattooing and other body modifications were reclaimed in the postmodern age (though not without detractors), sideshows and freak shows have tried to become something different than their earlier iterations. Many say they intend to be inspirational, empowering, and to realign conceptions about difference.

Maria Town, President of the American Association of People with Disabilities, told writer Kim Kelly, who trained as a sideshow performer: “Sideshows set the stage for modern conceptions of disability—identifying people with disabilities as objects of scorn and pity, as inherently ‘other’ from mainstream society. The disability stereotypes that sideshows perpetuated were what the disability rights movement sought to resist. However, even though sideshows were exploitive, they were spaces where people with disabilities, like famed [conjoined] performers Chang and Eng, began to assert their worth and curate how individuals looked at them… As people with disabilities work to reclaim sideshows and identities like ‘freak,’ modern sideshows become important sites for the development and proliferation of disability culture.”

• • •

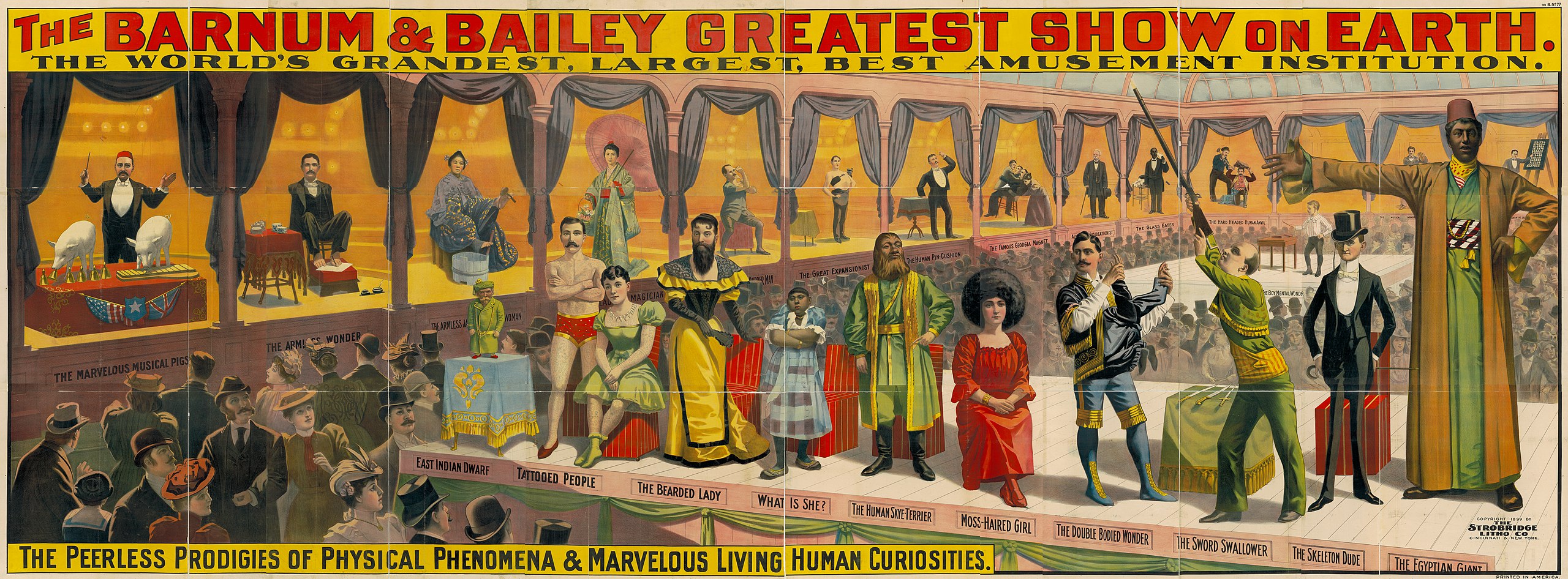

Barnum & Bailey Poster 1898-1899, courtesy Ddicksson on Wikimedia, CC 4.0 International.

People have always been intrigued and disturbed by difference, otherness. They sought out sideshows to be startled, if not scared. Most paid to be taken-in, willingly, for fun or catharsis, though a few, like people who think TV characters are real, were true believers.

Ward Hall, “King of the Sideshows” and the vendor who had the Illinois State Fair concession for many years, told writer James Taylor [brackets are from original]: “But one of the greatest [was when] I had a medieval torture chamber. And this very sweet old lady came up to the ticket box and said [to our lady ticket seller], ‘Miss, how long do you have to wait?’ And [my ticket seller] said, ‘Oh, you don’t have to wait. You can walk in right now and see it.’ And she said, ‘No, I mean how long do I have to wait once I get in there?’ ‘Well, you don’t have to wait. It’s going on right now, you just walk through.’ ‘I don’t think you understand. Do you have chairs that I could sit down while I wait.’ ‘Wait for what?’ She says, ‘Well, how long does it take for one of them to die?’”

Even death can be made to be okay, if it is part of the show.

• • •

The advertised climax of the Hellzapoppin Circus Sideshow Revue, “world’s largest international touring rock-n-roll circus sideshow,” is the moment Short E. Dangerously, “a real live half-man that is cut in half at the waist…walks bare-handed on razor sharp broken shards of glass…while on fire!” To be clear—not that it lessens the act—the glass is set ablaze, not Mr. Dangerously, who performs in the tradition of Johnny Eck, a well-known actor in the 1932 Tod Browning film Freaks. According to the troupe’s website, Mr. Dangerously has been included in two recent volumes of Ripley’s Believe It Or Not!, “has a wax figure featured in Ripley’s museums all over the world, and…appeared on AMC’s Freakshow.”

But the most meaningful moment for me of the recent Hellzapoppin show at Red Flag in St. Louis in July was when a score of adult human beings in the audience jumped up and down with their hands in the air, like smart kids who know the answer in a classroom, vying to be chosen to go onstage to drink the contents of troupe member Eric Ross’s stomach.

Hellzapoppin that day was five performers. (A sixth will be added in September.) These included Bryce “the Govna” Graves, “creator, producer, director and sideshow stuntman,” as well as the show’s MC; Willow Lauren, former motorcycle stunt rider, illusionist, and fire eater; Lucian Fuller, juggler and unicyclist; Short E. Dangerously; and Eric Ross, street magician, “human blockhead,” glass eater, and professional regurgitator.

The most meaningful moment for me of the recent Hellzapoppin show at Red Flag in St. Louis in July was when a score of adult human beings in the audience jumped up and down with their hands in the air, like smart kids who know the answer in a classroom, vying to be chosen to go onstage to drink the contents of troupe member Eric Ross’s stomach.

The show had consisted of swallowed razor blades, dental floss mysteriously embedded in the neck, Mr. Dangerously’s handstands on a rotating drum, Mr. Ross’s fakir act in which he pierced his face, neck, and bicep with metal skewers, and fire-breathing by Ms. Lauren and Mr. Graves, all to blaring deathcore (a musical subgenre of heavy metal). Eventually there would be a high-rise unicycle act, juggling, and Mr. Dangerously’s glass-walking routine.

But in this segment, Mr. Ross took a moment to swallow two feet of surgical tubing. Another five feet hung out of his mouth. Ms. Lauren attached a huge syringe to the loose end of the tubing. The syringe could hold more than a quart of fluid, and she poured Miller beer (“the champagne of beers,” she pointed out) into it, followed by chocolate syrup. She swished Pepto Bismol in her mouth and spit that into the syringe too.

Eric Ross knelt, and Ms. Lauren very slowly pushed the big plunger on the syringe, to pump the mess through the tube into his stomach. Something seemed not to be going to plan; she worried over a kink in the hose and had to put the plunger handle in the pit of her arm and use both hands on the syringe to push it in harder. Mr. Ross gave her permission, with his eyes, to get on with it. Finally the fluid was safely out of sight in Mr. Ross.

The show had consisted of swallowed razor blades, dental floss mysteriously embedded in the neck, Mr. Dangerously’s handstands on a rotating drum, Mr. Ross’s fakir act in which he pierced his face, neck, and bicep with metal skewers, and fire-breathing by Ms. Lauren and Mr. Graves, all to blaring deathcore (a musical subgenre of heavy metal).

Ms. Lauren then made a pitch for the troupe’s geedunk for sale at a booth in the back and said they were adding “bio beer” to the menu this night. Mr. Ross stood and jumped around, mixing the contents of his stomach, then knelt again. There was a lot of talking and build-up, and it was clear the fluid was coming back out. I wondered how drunk Mr. Ross might get before they finished.

Ms. Lauren pulled the plunger back, slowly—Mr. Ross aided her with little gagging and heaving motions—until the murky fluid with its pink cast was back in the syringe. She asked for volunteers without explanation, but the implications were obvious. That was when audience members shouted and pleaded to be chosen. Four were picked and onstage were handed red plastic beer cups with the fluid in them. All four drank it to the lees.

• • •

“World’s Largest Traveling Freakshow,” St. Louis, July 23, 2022. Photo by John Griswold

The troupe’s website, which deems them “the world’s largest and last remaining troupe of sideshow freaks and circus performers,” says, “The tatted and pierced rock ‘n roll circus donned their greasepaint and costumes and headed back out on the road as the first live production to return to touring [after Covid restrictions] last year, leading the way by mounting their ‘Face Your Fears’ tour throughout America. […] Hellzapoppin desperately wants to inspire the world not to live in fear. […]

“‘Face Your Fears’ was meant to be more or less a metaphor of what we do as circus performers and the things we put our bodies through to entertain people,’ says [Bryce ‘the Govna’] Graves. […] ‘We gave people hope during the toughest times of their lives. The show allowed people to forget their fears, even if only for a brief time. We took on this challenge, one town after another, and we are slowly seeing things get back to what used to be normal.”

It did take guts—pun intended—for the lucky few to drink the contents of a dude’s stomach in front of a couple of hundred strangers, but was it really an occasion for them to face their fears? Who has ever feared having to do such a thing? The risk of infection (Covid, hepatitis, etc.) was probably very low. The daring was due to the revulsion, which probably came from the vaguely cannibalistic aspect of it, the connotations of medical perversion, the fact that a wet inside came out the wrong end, not as waste but as food product, slightly altered and perhaps contaminated.

Was the drinking of it self-empowering, as the new wave of old-school acts bark? After all, who else can say they have done such a thing? (Even if the liquid was switched out at the last minute, the people still volunteered to drink it, thinking it real.)

As my son said, after Mr. Ross had apparently skewered himself with several metal rods, and a young woman had run from the bar area to yell her approval, give metal salutes, and whip her hair in circles: “Middle school kids sit in cafeterias sharing videos of ISIS beheadings now. This is supposed to shock anyone?”

One reason this was the true climax of the show in St. Louis was that those audience members made the act about themselves. They got involved and were made to feel something authentic: I can do this; I can stand in a COVID box for two hours; I can drink the biles; I can take it.

We voyeurs, who did not leave, may have gotten our lesser portion, which other acts did not provide. As my son said, after Mr. Ross had apparently skewered himself with several metal rods, and a young woman had run from the bar area to yell her approval, give metal salutes, and whip her hair in circles: “Middle school kids sit in cafeterias sharing videos of ISIS beheadings now. This is supposed to shock anyone?”

Emma Louise Backe, managing editor of The Geek Anthropologist, writes, “Although the term designated a sense of social stigma and shame, circus and sideshow performers adopted the term ‘geek’ as a collective and positive form of identity…in opposition to the norms and rubes in the audience. […]

“To be a geek, therefore, was to be set aside from ‘normal society.’ Freaks or geeks were a community separated by physical difference, as well as social taboos and codes of morality at the time. […] Who a society deems to be freakish is exceptionally telling of a culture’s system of moral codes, ideologies and structures of power and class. […] As a cultural rather than an overtly physical condition, freakery/geekery meant, to a certain extent, ‘to be accepted into a community unified on the basis of shared marginality’ (Adams 2001:42).”

The “biobeer” stunt was a way to include the audience in a constructed, shared, cultural marginality. This is the new wrinkle in these old forms. Short E. Dangerously, on the other hand, represented not only the old freak shows but also the only “overtly physical” marginality in the troupe. He gave a speech about how he had been stared at his entire life, but now people had to pay to stare at him. It was not a joke, and the audience clapped confusedly. Was he talking about those other audiences?

One sideshow act was made “okay”; the other was not. This discomfort reflects our society.

• • •

Artist Tim Prince of Forgotten Boneyard sells embellished skulls, St. Louis, July 23, 2022. Photo by John Griswold

It was coincidence that the same week Hellzapoppin was in town, the “Oddities & Curiosities Expo, For Lovers of the Strange, Unusual & Bizarre,” was held at The Dome at America’s Center in downtown St. Louis.

The Expo, which is held across the country, “showcases hand-selected vendors, dealers, artists and small businesses from all over the country with all things weird. You’ll find items such as: taxidermy, preserved specimens, original artwork, horror/Halloween-inspired pieces, antiques, handcrafted oddities, quack medical devices, creepy clothing, odd jewelry, skulls/bones, funeral collectibles & much more. We truly have something weird for everyone at our shows. All items you see at our shows are legal to own and sustainably sourced.”

“I’m not gonna lie,” my younger son said in the Dome. “This is kind of boring.” Even the jewelry made with human blood, and the man and woman who let people staple five-dollar bills (or higher) to their arms and legs failed to impress. I paid extra to walk alone through the “world’s largest traveling freak show,” so I could use my impressions here, and because my sons refused to let me pay for them since they said it was “going to suck.”

I asked in a couple of different ways if there was something about the punk aesthetic that chimed with the Expo—I even explained Hellzapoppin—until I saw I was trying to lead her answers, so I gave up. She just liked what she liked, was her guess.

It did suck, because it was another hokum switcheroo, the kind drawing in rubes like me with signage that said, “Over the years, freaks have brought wonderment,” and inside giving amateur explanations of scientific concepts (Papilloma, Albinism, Conjoined Twins, Cyclopia, Hydrocephalus, Diprosopus, Polycephaly) next to deformed animal skeletons.

Before we left I spoke for several minutes with the Expo organizer, a hardworking young woman who owned a punk record shop and a silk screening business that made punk-themed clothing in another state, and now the Expo, a full-time job by itself. I asked in a couple of different ways if there was something about the punk aesthetic that chimed with the Expo—I even explained Hellzapoppin—until I saw I was trying to lead her answers, so I gave up. She just liked what she liked, was her guess.

We are all fallen bearers of light, sitting hunched, looking at the world as it is, a bunch of hard stones, some with glints of perfection.

I was reminded of that brief chapter in Harold Bloom’s The Shadow of a Great Rock, his appreciation of the King James Bible as literature, in which he performs an exegesis of the Gospel of Mark. Bloom says “… Mark reminds me of Edgar Allan Poe, a bad stylist who yet fascinates. Both dream universal nightmares.” (248) He flirts with his thesis that “only the devil in each of us has a hope finding” what is divine, (251) as he says in his chapter on Ecclesiastes that “the book’s universal appeal depends upon the Fallen Angel in every reader.” (213) We are all fallen bearers of light, sitting hunched, looking at the world as it is, a bunch of hard stones, some with glints of perfection.

The Expo crowd wore fetish and punk outfits or polos and dad jeans; made soft exclamations over little pickled things in row upon row of paperweights for sale; envied the huge array of taxidermied heads and laughed at small furry beings posed doing ridiculous things; flipped through Edgar Allan Poe and Vlad the Impaler prints; and considered skulls bedazzled with crystals.

Bones were brought to light, blood brought to light, fetish objects brought to light, death brought to light, under the dome far overhead. It would all be gone the next day, and some different show would come to light then. Everything would be okay.