Mankind has multiplied, has burst its bounds:

nothing, sweet soul, is as it was before.

—Wisława Szymborska, “On the Banks of the Styx”

Eighty acres is a big piece of land—big enough to be a significant part of “the landscape” that gives a place identity. By comparison, a football field is only 1.32 acres, a New York City block five acres.

I just walked around the perimeter of what was, until recent years, an 80-acre farmstead between the city of Edwardsville and the village of Glen Carbon, Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis in the “Metro East” counties. It took 40 minutes to walk the somewhat hazardous 2.2-mile perimeter.

What remains of the Foucek tree farm, as it is called, is in the strip-mall and big-box district on the border of the two towns, outlined by busy roads that often lack sidewalks or crossing signals. Just two years ago a local historian wrote in the Edwardsville Intelligencer, “Turkey, deer and other wildlife still inhabit the 54 remaining acres of the old…farm. The quiet pastural neighborhood is nearly gone and what some call progress is coming.”

The gaze slips past what used to be trees, scrub, and prairie grasses, and skids off toward the horizon. The mind flashes a kind of warning: desecration

Since December 2021 the violence of that progress has been unrelenting: excavators razing the farmhouse; logging machines cutting and piling trunks; earth movers scraping up all living matter down to bare dirt; dump trucks carting it away; clouds of dust obscuring the setting sun; roadside trash blowing in the wind; deer standing confused at midday on nearby bike paths.

The scale of the newly-naked landscape, its vegetation stripped, is as disorienting to local motorists as it must be to wildlife. (The only people walking it are the poor and me.) The gaze slips past what used to be trees, scrub, and prairie grasses, and skids off toward the horizon. The mind flashes a kind of warning: desecration.

• • •

The original downtowns of Edwardsville and Glen Carbon are five miles apart. Both towns were settled early in the nineteenth century, and some of the first structures of White men in the region were log blockhouses or stockades called Kirkpatrick forts, “built as protection from Native Americans.” One of these was on the Foucek farm, then part of a larger parcel deeded as bounty land by the US government to Francis Kirkpatrick in 1814. The parcel was divided, and the farm sold to a McKee family in 1830, then to the Fouceks in 1944.

Edwardsville and Glen Carbon became brickmaking and coal-mining towns, rail hubs, and commerce centers. Edwardsville is also the county seat. For more than a century the population grew slowly, but in 1965 Southern Illinois University added a satellite campus in Edwardsville, and white-flighters, other St. Louis commuters, and people moving in from smaller towns for work and services started buying homes. Glen Carbon’s population grew more than 500 percent from 1970 to 2010. Edwardsville’s almost doubled after 1990. About one in four St. Louis-area residents now lives in the five Illinois counties (and parts of others) of Metro East.

Edwardsville City Planner Emily Calderon told me by email, “Speaking as someone who grew up in Edwardsville, I have always viewed this community as part of the ‘Metro East Region.’ […] Our community has been growing and changing consistently for as long as I can remember, but I think the true acceleration of development occurred beginning in the early to mid 2000s.”

As the towns sprawled toward each other, the Foucek farm, at what is now Governor’s Parkway and Troy Road, was the last large property to be developed. It had been owned by only the three families since 1814 and was, by newspaper accounts and social media comments, a lovely place where wildlife took shelter among dogwood trees and Japanese Maples.

In 2002 the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) planned to build a bypass road to get commuters to and from the highway more rapidly. It would cut off 18 acres, almost a quarter, of the farm.

Michael Pierceall, executive director of the Alliance of Edwardsville and Glen Carbon, a development nonprofit, told an Indiana publication that the bypass was needed “to support all this growth we’ve seen.”

Joanne Foucek, who ran the nursery then, fought what she called “a mighty [legal] battle” but lost on appeal. The ruling made a point of denying “conspiracy” in the push for the bypass. It acknowledged the “land had been farmed for more than 200 years” but would not permit invocation of the Farmland Preservation Act because the property did not produce food.

IDOT also took six acres by eminent domain for its road.

Foucek said dividing the farm would “kill her father’s dream of eventually converting the land into a public arboretum” that “would be a respite from the development and from the traffic and hectic lifestyle everybody has nowadays [and] would be a legacy for future generations.”

The farm was a bubble of Glen Carbon rising into Edwardsville because the Fouceks had previously “requested to annex into the Village [of Glen Carbon] and did so on November 15, 1988,” Stacy Jose, Building & Zoning Administrator, Village of Glen Carbon, told me by email. “They were interested in receiving municipal services from the Village.”

As a result the bypass, Governor’s Parkway, was almost entirely in Edwardsville, except where it ran through the Foucek property. Edwardsville’s City Administrator said that if he were Joanne Foucek he would not like a new road either, “but there are a lot of things we’re forced to do to plan for the future and meet the needs of the majority.”

Edwardsville Crossing became a strip mall with Dierbergs as its anchor. Joanne Foucek told the Intelligencer in 2004 that she was put under “extreme and urgent, threatening pressure” to sell the 18 acres, which became “out-parcels for development” at The Crossing—now a Men’s Wearhouse, Texas Roadhouse, Best Buy, Starbucks, etc.

The northernmost edge of the cut-off acreage abutted county land in Edwardsville—at one time the tuberculosis sanitorium—that was about to be developed. Though one Glen Carbon Village trustee called the nursery “a sanctuary amid all this madness,” the Village of Glen Carbon rezoned Foucek’s 18 acres from “agricultural to general commercial.” This was done at the request of “Edwardsville Crossing, LLC, a joint venture between Dierberg’s [a supermarket chain based in Chesterfield, Missouri] and Capital [sic] Land Co.,” according to the Edwardsville Intelligencer.

Edwardsville Crossing became a strip mall with Dierbergs as its anchor. Joanne Foucek told the Intelligencer in 2004 that she was put under “extreme and urgent, threatening pressure” to sell the 18 acres, which became “out-parcels for development” at The Crossing—now a Men’s Wearhouse, Texas Roadhouse, Best Buy, Starbucks, etc.

Foucek said “the land that for so long provided a safe habitat for wildlife and the green places so essential to life will instead be a barren place of concrete and asphalt.” She died in 2011.

Another long strip mall sits across the busy road from the remaining acres of the farm’s eastern side, anchored by a Target and out-parceled by a different supermarket, a tire shop, big-box liquor store, gas station, and fast-food places. A smaller, cheaper strip mall and a bank sit on the farm’s southern side. The southwestern corner is hemmed in by a multiplex theater, a Planet Fitness, and a recently-built strip mall that houses a “craft” brewhouse with six locations in three states, a chain barbecue restaurant, and an already-defunct shop called Strange Donuts.

Now, that central portion of the farm, more than 51 acres, is being prepared for yet another huge strip mall (named, predictably, Orchard Town Center) that was called by a regional business publication “one of the last ground-up retail projects built in the St. Louis region.” Timothy Lowe, Senior Vice-President, Leasing and Development, of developer The Staenberg Group, told me by phone that the company bought the land from the Foucek family in Fall 2021, for $11 million.

The Staenberg Group, headquartered in St. Louis, specializes in strip malls and has “a portfolio of more than 200 shopping centers comprising in excess of 45 million square feet of quality retail space,” its site says. “Customer satisfaction is critical to our success and we strive to exceed the expectations of our tenants, partners and customers (internally and externally) by anticipating, understanding and responding appropriately to their specific needs.” Community needs and the natural environment are not mentioned.

A crescent of county land on the farm’s western edge has also been sold to the developer, despite the efforts of a small but vocal conservation group called Plum Creek Greenspace. The Intelligencer reported that the Madison County Administrator “said the county wanted to sell the site so it does not have to maintain it, and to eliminate the county’s liability. He said he understood the desire to retain it as greenspace,” but, “’It is an area that is sought after for development…. The problem is we don’t do parks.”

Madison County Board Chairman Kurt Prenzler said the land was “‘very valuable,’” that “Madison County has plenty of greenspace and habitat/wildlife conservation areas,” and that “’If we’re looking to protect habitat, I don’t think this is number one on the list.’”

The developer is still looking for tenants, but a car wash is planned—it would be the third in a half-mile radius. “Competition” among redundant businesses is often said to be beneficial to consumers, but that does not necessarily make it a community good.

There was “some blowback from residents about the tax increment financing (TIF)” being used to develop the former farm, but Glen Carbon Village trustees explained that its property tax had been “less than $7,000 dollars a year, [but] when built out, it would be several hundred thousand dollars a year and that money would go into the TIF…to be available to reimburse part of the expenses for improving the public roadways and improving some of the conditions that are already causing traffic jams.”

In other words, development of the farm into a strip mall would help pay for what the glut of strip malls in this business district had caused.

Some residents also did not approve of the redundancy of the businesses, such as a planned Menards that would have been the “fourth lumber/home improvement store” in the area. Menards pulled out of the project, but a Meijer is expected to sign a deal to replace it and become the fifth supermarket within a mile. The developer is still looking for tenants, but a car wash is planned—it would be the third in a half-mile radius. “Competition” among redundant businesses is often said to be beneficial to consumers, but that does not necessarily make it a community good.

• • •

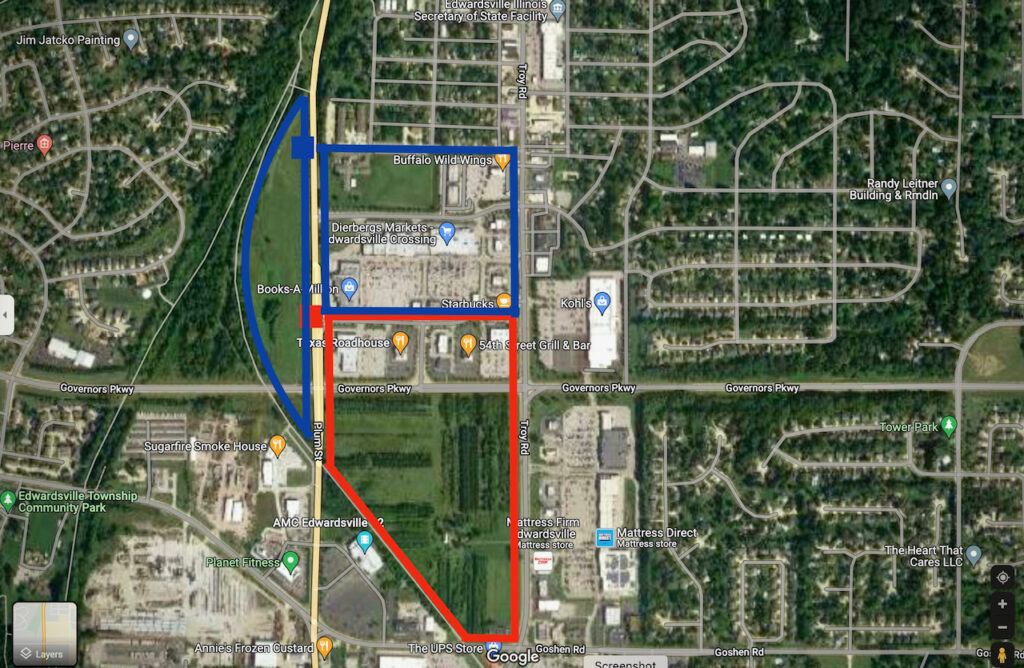

This map shows the boundary, outlined in red, of the original Foucek farm, and the boundary of former county land, outlined in blue, that lie in the business district at the borders of Glen Carbon and Edwardsville, Illinois. Orchard Town Center, a new shopping center, is being built on the 52 acres of (once-)green area within the red line. Courtesy Google Maps.

In the last decade, urban areas in the United States have been growing by a million acres per year—the amount of land used by Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Houston combined. The St. Louis Metro area continues to build despite a net loss of population, including in Metro East—even in parts of Madison County.

“This trend is a bit confusing for some,” KMOV St. Louis says.

Despite recent growth, Edwardsville proper still has fewer than 27,000 residents, and Glen Carbon fewer than 13,000. Yet traffic is often bad, and the density of businesses, subdivisions, and new college-style apartment complexes feels very high. A relative of mine who has lived here for decades says the landscape is “unrecognizable.”

In the last decade, urban areas in the United States have been growing by a million acres per year—the amount of land used by Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Houston combined. The St. Louis Metro area continues to build despite a net loss of population, including in Metro East—even in parts of Madison County.

I asked Emily Calderon, Edwardsville City Planner, by email why the city feels more congested than its population would seem to warrant.

“It may feel like a larger city because it’s an employment destination, with SIUE, corporate headquarters such as Scott Credit Union, Prairie Farms, and Hortica, to name a few,” she said. “Edwardsville is also the County Seat of Madison County, so we see a large influx of jurors, attorneys, etc. during the work day. It’s also important to consider that many residents of the smaller communities surrounding Edwardsville (e.g. Worden, Hamel, Marine, etc.) may frequently travel to Edwardsville for personal services, dining, and shopping.”

Glen Carbon also has businesses along Routes 159 and 157 but is known as a bedroom community for better-educated professionals and families. It ranks number one or two for best places to live in the county, and in this way it and Edwardsville complement each other.

The blurring of the towns’ boundaries around the Foucek farm is to their mutual advantage, as it offers the impression of vitality—even its ugliness impresses—and that has brought more development, tax revenues, and certain kinds of jobs.

In many places in the United States, Walmarts on the edges of towns killed their downtowns. Here, the big box stores, including a Walmart Supercenter, help pay for old downtowns not built for cars. (Downtown Glen Carbon, a former company town for the mines, is little more than a pub and grill, a good library, a town museum, a covered bridge, a historic log cabin, and a few small houses. Maintaining that vibe is written into its Village plan.)

In many places in the United States, Walmarts on the edges of towns killed their downtowns. Here, the big box stores, including a Walmart Supercenter, help pay for old downtowns not built for cars.

Illinois Route 159, diverted from the eastern side of the Foucek farm to its western side in 2003 in order to relieve congestion in the strip-mall district, runs as a five-lane highway from Edwardsville down through Glen Carbon, Maryville, and Collinsville to Fairview Heights, known since 1974 for having the nearest indoor mall. Route 159 still has plenty of land left along its length for development, but it is already showing signs of becoming a strip-mall megalopolis; the Metro East Corridor of tin-roof retail; a mattress store no one asked for, surrounded by five corporate purveyors of slightly-different chicken sandwiches.

• • •

What interests me more, however, now that Orchard Town Center is a done deal and the former Foucek farm stripped bare, is the welfare of local wildlife during this kind of development. That is harder to know, in part because the animals seem prolific. That is the other side to this story, and the reason there is tension in the growth of these towns unlike others’ in the region.

White-tailed deer are everywhere: in subdivision backyards, eating from bird feeders; dashing across roads single-file; sheltering along 130 miles of narrow bike and walking paths that Madison County Transit District converted from rail beds; and grazing at dawn and dusk on SIUE’s wooded campus.

“Madison County leads the state in vehicle crashes involving deer,” St. Louis Public Radio reported in 2016. There were 440 such accidents in 2015, while St. Clair County, where the mall is, reported 212 crashes. I have seen it myself, on a visit to Edwardsville: a deer lying in the middle of Route 157 at night; the damaged car; a handful of does watching worriedly from the tree line in the spin of police lights.

White-tailed deer are everywhere: in subdivision backyards, eating from bird feeders; dashing across roads single-file; sheltering along 130 miles of narrow bike and walking paths that Madison County Transit District converted from rail beds; and grazing at dawn and dusk on SIUE’s wooded campus.

A year ago I encountered a strange couple in Edwardsville Township Community Park, close to the Foucek farm. They had found a fawn, in the middle of the day, resting in a mown field under the Navy fighter jet on a pedestal there. Does will leave their fawns in the open and come back for them later; they should always be left untouched. This woman had the fawn in her arms as her husband tried to control their dog. I called the police, but by the time they responded the couple and fawn were gone; a doe trotted frantically around the shelters looking for her baby.

Coyotes howl in the night, as neighborhood chatrooms cry warnings about locking up little dogs. The usual shrub mammals of the urban landscape are present—raccoons, possums, foxes, woodchucks, chipmunks, squirrels, skunks, and rabbits—and the bigger birds of the Midwest savannah, including wild turkeys, Canada Geese, and vultures, are often seen. The bike-trail woods are filled with bird song, though I cannot say how many species that represents. Murders of crows work together on trash cans at the curbs, tossing out garbage and inspecting it like burghers. Roadkill regularly lies in the gutters along the diverted stretch of 159 between the Foucek farm and downtown Edwardsville.

When I asked local authorities about the effect of razing the Foucek land, several told me to talk instead to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR). IDNR’s spokesperson in Springfield said their people would not speak directly to that particular development, as “That’s not what we do here.”

I asked the spokesperson more generally “about mammals and birds in this region—how they’re doing among the agribusiness fields and growing human centers, what deer numbers are, and what challenges exist because of overpopulation, disease, traffic accidents, and backyard encounters…[h]ow they get enough to eat in what must be food deserts.”

Her response was, “We’re not going to be able to help much with this (our wildlife biologists are absolutely swamped in the field right now),” and she directed me to general web pages.

A local conservation professional who asked not to be named is familiar with IDNR practices. I asked who would look out for wildlife in cases like the Foucek farm.

When I asked local authorities about the effect of razing the Foucek land, several told me to talk instead to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR). IDNR’s spokesperson in Springfield said their people would not speak directly to that particular development, as “That’s not what we do here.”

“I think you know the answer,” the person said. Development is the “proven winner in this battle.

“There are not too many deer, but a lack of habitat and natural predators,” they said—the bobcats, mountain lions, wolves, and bears wiped out since the time of the Kirkpatrick forts.

“This is an equation of time and resources,” the person said, “confounded by priority. It’s difficult to see that the state’s managed areas or wildlife populations have those factors… And there is more work than can ever be done.”

• • •

Looking across the former Foucek land, now cleared, from a Madison County Transit trail. Photo by John Griswold.

Eric Wright, Land Conservation Program Manager for Heartlands Conservancy, “southern Illinois’ largest conservation nonprofit,” acknowledged in a call the challenges to his organization’s mission but also told me to note ways the towns were planning to conserve wildlife areas and other green spaces.

He mentioned Bohm Woods Nature Preserve, 92 acres managed by IDNR in Edwardsville that is one of the few old-growth forests left in the state; the adjacent William C. Drda Woods, 72 acres of former farmland being reforested by Edwardsville as a buffer to Bohm; the 40-acre Watershed Nature Center owned by Edwardsville and managed by the nonprofit Nature Preserve Foundation; and Richards Woods, “one of the few natural timbered areas in the Edwardsville area that has survived suburban development” and is part of Edwardsville’s “200 Acres for 200 Years” program commemorating its anniversary and setting aside land for future generations.

Wright also said the extensive rail-trails system, which runs all the way to St. Louis, would let deer travel on them (but that they probably are not the same population as those along the bottoms of the nearby Mississippi River).

The village has planned and created green spaces—a phrase wide-open to interpretation—on west and east to mitigate development.

SIUE’s Superintendent of Grounds, Peter (Kert) MacLaughlin, told me by email that he believes 75-80 percent of the school’s 2,660 acres is deer habitat, though they do not manage the deer population and have no information on the size of the herd.

Glen Carbon’s comprehensive plan, updated February 20, 2015, when the Foucek farm was still shown on zoning maps as “agricultural land,” explains that the village’s growth will be necessarily limited by the bluffs and River floodplain to the west, and by some areas over old mines that could subside. The village has planned and created green spaces—a phrase wide-open to interpretation—on west and east to mitigate development.

The plan also says, “The pastoral setting of the Village should be maintained.” “Commercial buildings should be more understated, avoiding big box shapes that do not blend in with the residential surroundings.” “Natural resources, such as bluffs, hills, waterways and trees, shall be preserved [as well as] the existing landscape to the greatest extent possible.” “Open space should be preserved through economic incentives such as purchase of development rights and acquiring green space easements.”

Given the loss of the Foucek farm, which would have helped serve all these goals, a funny but familiar feeling rises—that as priorities change something worse can always happen to the landscape.

Are these towns a good model for conservation in American suburbs in the age of sprawl? Or are they creating a situation that fosters more conflict and justifies more development?

• • •

Humans’ relation to the earth seems to be based in one of two archaic attitudes: The natural world is terrible (the progenitor of terror), or it is awful (filling us with awe). These attitudes determine how we will treat the only planet on which we can currently exist.

In the ledger of life there is a true bottom line—sustainability—and most business ignores it by looking only for opportunity. The profit motive does not care if what is sold is frippery or redundant, or if its temples to commerce create more traffic, pollution, ugly sterility, heatsinks, and buildings that age poorly. Much business gives nothing back to the earth and is therefore killing us slowly or quickly.

An Edwardsville resident wrote in an op-ed at the Intelligencer, “The Foucek property could have been our Central Park between the two communities. That would benefit people. Instead, we get redundancy after redundancy.”

Jay, a member of the Plum Creek Greenspace group that fought the sale of county property to the developer, told me on the phone that she is in sales and marketing and would not call herself a “conservationist per se,” but she has an interest in local government maintaining livability for its residents.

An Edwardsville resident wrote in an op-ed at the Intelligencer, “The Foucek property could have been our Central Park between the two communities. That would benefit people. Instead, we get redundancy after redundancy.”

“Edwardsville is a desirable place” to live, she said. She would not like to see it go the way of other towns that have been overdeveloped, that suffer by duplication, or were lost to “concrete palaces.” Land, she believes, should be used for “what the city really needs, instead of being sold to the highest bidder.”

“It is hard to say what the city does need most,” she admitted. She said her group would “love it” if The Staenberg Group left the crescent of county property “as is,” especially since it is “too small for a big-box store or other large project.”

“I did reach out to the developer,” she said. “We had a group meeting to open a dialogue. I felt that was very positive [in order] to help educate both sides. I think people just want [the property] to be something that leans toward a natural aesthetic that they can enjoy. We would like them to leave it alone. But that’s not going to happen.”

I asked Senior VP Timothy Lowe of The Staenberg Group on the phone about the county land being left undeveloped, or if a public statement by Glen Carbon’s mayor was accurate that there would be more opportunities for green spaces and walking access around Orchard Town Center now that Meijer, with a smaller footprint than Menards, seemed the likely anchor tenant.

He would only commit to telling me: “All of our landscaping and greenspace will follow Glen Carbon code. Our plan and intent is to follow their code.”

I asked Lowe if Staenberg Group would like to comment on local resistance to the development—redundancy, appearance, traffic, that it could have been the “Central Park” between the two towns.

“Municipalities always have the ability to acquire properties for other uses,” he said. “Neither elected to do that.”

I asked if President Michael Staenberg, known for his philanthropy in St. Louis, had considered donating to green projects in either of the towns as a way to offset the effects of the shopping center.

Glen Carbon; Edwardsville; their residents; local, state, or national conservation groups—none had the interest, or found the political will or money, to buy the Foucek farm for another use. And its 51.39 acres, in the heart of the busiest area of both towns, cost only $11 million, which seems like a deal. It is, more often than not, how these things go.

Lowe said Orchard Town Center was “bringing something to Glen Carbon that doesn’t exist today” and mentioned jobs, revenue, services, and amenities.

“The project itself is an amenity for Glen Carbon,” he said.

Even critics of the “Walmart Effect” must acknowledge that towns allow the company in, and consumers choose to shop there, both of which likely affect smaller businesses in the area. Glen Carbon; Edwardsville; their residents; local, state, or national conservation groups—none had the interest, or found the political will or money, to buy the Foucek farm for another use. And its 51.39 acres, in the heart of the busiest area of both towns, cost only $11 million, which seems like a deal. It is, more often than not, how these things go.

• • •

The day I decided to write this essay, my family and I were driving up the diverted Route 159 toward downtown Edwardsville. We were near a spot, behind the Edwardsville Crossing strip mall, where three MCT Trails converge. I have learned to drive very defensively in this part of town, though the speed limit is 40 miles per hour. I saw motion in my peripheral vision and braked hard.

It was hard to believe what we saw—a spotted fawn running and dancing around another one lying in the grass a few feet from the road. They looked like two deer in a Disney movie. The running fawn charged blindly at our car, looked up at the last second, mildly surprised, then swerved and ran around a young tree and back to its twin or friend. They touched noses.

Other cars crowded in behind us, and though my slowing alerted their drivers to something most could not yet see, I knew there was no solution to the immediate problem. We drove on, hoping for the best.