1. The Judgement Seat

In the last twenty or so years, I have taken two trips to Israel, sponsored by two different American Jewish organizations, in the company of fifteen to twenty other Blacks. The main purpose of the trips was for us to return to the United States with a positive view of Israel to counter a growing antisemitism Jews sensed among American Blacks. We were considered influential people in our community. (I was over-esteemed in that regard.) On both trips, our Israeli hosts were generous enough to have us meet and talk with Palestinians. I suppose, in one respect, the Israelis had to do that in order to convince us that they were on the square, had nothing to hide. They may have thought that because we were Black, we might especially want to hear from Palestinians. In any case, the ones we met, men whose accented English was quite good, clearly intellectuals, spoke frankly, sometimes with deep anger, sometimes with great sadness, about their situation, about the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, about the Israeli settlements, about Israeli atrocities, and Israeli terrorism. All of us were profoundly moved by these tales of injustice and brutality. Many of us quickly saw the Palestinians as if they were Blacks in Birmingham in 1963, and the Israelis, in our imagination, became Bull Connor and his cops. Or they were Blacks in East St. Louis in 1917 or in Tulsa in 1921. I said nothing during our sessions with the Palestinians, but others spoke with great sympathy for their plight, with a sense of identification. Some of us seemed angry about it all too.

It felt like a case of competing narratives of suffering: the Palestinian refugees, the Jewish exiles who came to Palestine, and the Black Americans, the ex-slaves, who were, at the moment, sitting in judgement.

I thought, “Well, what else could the Palestinians say but this? That is why they are here. To tell us this. It makes this tour genuine. The hatred of the Palestinians is part of the Israeli experience. The Israelis are giving us this to make sure we do not leave this country feeling we had been cheated or denied.” The room we were in felt increasingly airless and tense, despite the fact the Palestinians and the Israelis in the room were quite civil to each other. The Israelis would leave the room periodically. I had a cup of strong black, tepid coffee in front of me that I did not ask for. Suddenly, I drank some, although I despise coffee. It was bitter and simply made me more agitated. Being unused to coffee, I knew I would not sleep that night. After a while, I just wanted this ordeal to end. What was I supposed to do? Weep? Curse the Israelis? Defend the Israelis? Pick the righteous side? Shrug and say, “I am a Black American and I have got problems of my own. You people have been warring before I was born, and you will be warring after I am dead”? It felt like a case of competing narratives of suffering: the Palestinian refugees, the Jewish exiles who came to Palestine, and the Black Americans, the ex-slaves, who were, at the moment, sitting in judgement. Sensing how we were interpreting what the Palestinians were saying, one of our Israeli hosts told me after the session that we should not look at the Palestinians as if they were American Blacks and as if this was like the American race problem. “It’s a different history,” he said, “with very different actors in a different place.” I agreed with him wholeheartedly but said it could not be helped. I told him that Black Americans, like everyone else, are prisoners of their experience.

Despite our concerns about the Palestinians, when we departed we all had positive feelings about Israel.

2. How some Black Americans turned against Israel

But [the Jew] was faced always by three alternatives: Should he lose himself in the surrounding population and through that give up his peculiar culture and religion; should he keep to himself, an integral unit; or finally, should he try to found a state of his own?

—W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Case for the Jews” (1948)1

When should the Jews stay put and when should the Jews run?

—Masha Gessen, Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region (2016)

I first heard the expression “Occupied Palestine” not in recent demonstrations, on college campuses and elsewhere, by anti-Israel, pro-Hamas, and pro-Palestinian supporters in response to the ferocious October 7 attacks against Israel. I first heard it nearly fifty years ago in the late 1960s, probably around 1968 or 1969 when my sister, a former member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), used it. Other former civil rights workers my sister hung around with used it too. Haki R. Madhubuti, then still known as Don L. Lee, used it in some book of poetry or perhaps one of his prose books I read. Or was it singer/poet Gil Scott-Heron? Maybe both. So, it had seeped into the Black Arts literary and creative circles as well. I had no idea what it meant. It almost seemed hip to utter it, as if someone had some secret revelation about the crimes of this world.

Until the June 1967 Six-Day War, I was so ignorant I could not have found Israel on a map if my life depended on it. But as I attended a public high school that was nearly 70 percent Jewish, I, as you might say, got a quick and intense education about the Arab-Israeli conflict in the tenth grade, or at least one side of it. So, now, hanging out with my sister and her radical friends, I was getting an education in another side with the phrase “Occupied Palestine.” It was not referring to Gaza or the West Bank, among the territories that Israel won in the 1967 War. I learned it was referring to Israel itself. It clearly reflected the user’s view that Israel was an illegitimate state, a colonial enterprise. The Jews were Euro-White oppressors. In retrospect, it is fairly easy to explain why young Black folk like my sister, who was twenty-two years old in 1969, were anti-Israel:

First: The influence of Black psychiatrist Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (originally published in French in 1961), a book that had become a kind of bible among the young radical Blacks of the late 1960s. Fanon, from Martinique, who wound up practicing medicine in Algeria, was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front during the Algerian War. The chapter “On Violence,” a consideration of the necessity of violence by the colonized against their oppressors, not only as a political weapon but as a form of psychological redemption from the alienation caused by the cognitive dissonance of colonialism on the colonial subject, was particularly talked about and discussed. “… decolonization is always a violent event,” writes Fanon on the first page of the book, a phrase that has become in recent demonstrations a kind of thoughtless slogan.2 Fanon provided two important frames for Black American leftists to analyze their situation.

The first was through the lens of colonization. Blacks were not a group of second-class, mistreated citizens denied their civil rights and properly seeking redress by legitimate means that recognized the legitimacy of the political process of the United States; they were a brutalized colony entrapped by an oppressive, immoral, illegal regime, born of theft and murder, that must be overthrown. This, for younger activist Blacks, ended the debate about the efficacy of nonviolence as a tactic for social change. Violence was now not only justified but was also valorized. “Long live the revolution!” as I heard many of my sister’s friends say.

The second was the idea of identification with other peoples of color around the world who were fighting colonization. We must form a common cause to dismantle the West, not be absorbed by it, so this line of reasoning went. This, at the time, was called something like the ideology of the Third World or Third Worldism, which espoused, if not a blatant Marxist view, something called non-alignment (Nehru of India was a big proponent of this, as was Nasser of Egypt and Nkrumah of Ghana), neither capitalist nor communist, which the Cold War-era United States particularly distrusted because it was the position essentially of leftist sympathizers. This Third Worldism was canonized with the 1955 Afro-Asian Unity Conference or more properly the Asian-African Conference which took place in Bandung, Indonesia, a gathering of Asian, Arab, and African nations that did not include the United States or Europe or, naturally, Israel. Richard Wright wrote a journalistic account called The Color Curtain (1956), describing it as “The despised, the insulted, the hurt, the dispossessed—in short, the underdogs of the human race were meeting.”3 Yes, the underdogs versus the big dogs of the White West. Journalist Carl Rowan also covered the conference as part of wider reportage on Asia in his 1956 book The Proud and the Pitiful (his section on the conference is called “The Voice of the Voiceless,” an expression that has become a cliché among social activists today), and Malcolm X completely apotheosized the conference in his famous 1963 speech, “Message to the Grass Roots,” the recording of which spread around younger Black circles, particularly after his death in 1965. He said about the conference, “It actually serves as a model for the same procedure you and I can use to get our problems solved.” Malcolm tried to mimic something like it with his Organization of Afro-American Unity, which clearly took its inspiration from the Organization of African Unity. This may explain why Black radicals who were fleeing the United States in the late 1960s went to places like Cuba, Algeria, North Korea, Nkrumah’s Ghana, and China but not necessarily the Soviet Union.

Second: Although the vast majority of Black Americans who practice a religion are Christian, Islam had made considerable inroads during the 1950s and 1960s. The Nation of Islam was the most publicized of the various sects of Islam—all of which targeted Blacks for membership—that existed in the United States, but it did not necessarily attract the most adherents. Sunni (Ahmadiyya) Islam had many Black American converts and famous ones, lest we forget Black jazz musicians like drummers Art Blakey and Idris Muhammad, saxophonists Yusef Lateef, Pharoah Sanders, and Sahib Shihab, pianists Ahmad Jamal and McCoy Tyner, trumpeter Idrees Sulieman, and singer Dakota Staton among others. Islam was always touted as “the Black man’s true religion,” not the slave master’s religion like Christianity. Young Blacks may not have converted to Islam much but there was an air of being a fellow traveler, of taking on the moral airs and dietary practices of Muslims among non-Muslim Blacks. Eating pork among young college-educated Blacks became distinctly unpopular, as I remember. Sufism was also quite popular in the early 1970s even among counter-culture Whites. This rise in Muslim consciousness, as one might describe it, further intensified a sense of identification between American Blacks and Palestinians, by connecting American Blacks with Arabs and Arabic.

On the other hand, Black conversions to Judaism have not always resonated in the same way among Blacks as Black conversions to Islam. When singer/dancer/actor Sammy Davis Jr. became a Jew in 1961, many perceived this as his attempt to assimilate with the Jews in the entertainment industry, as if he were some insincere toady. There is no evidence that his conversion was some kind of gimmick or that he was not serious about it. Writer Julius Lester wrote a book, Lovesong (1988), about his 1982 conversion to Judaism in which he criticized some remarks James Baldwin made as antisemitic. He was promptly dumped by the Afro-American Studies department at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst because it was felt Lester irresponsibly mischaracterized Baldwin’s comments. Lester was then solely appointed in Judaic and Near Eastern Studies. The Afro-American Studies department offered an explanation of its actions here. But the upshot was that one Black person accusing another, especially a highly regarded figure such as Baldwin, of antisemitism, was made even more controversial when the accuser is also a Jew. Lester might have asked what would have happened had a faculty person in the department taken Baldwin to task for being insufficiently critical of the Jews. In both cases, it was almost as if both Davis and Lester had ceased, in some way, to be Black.

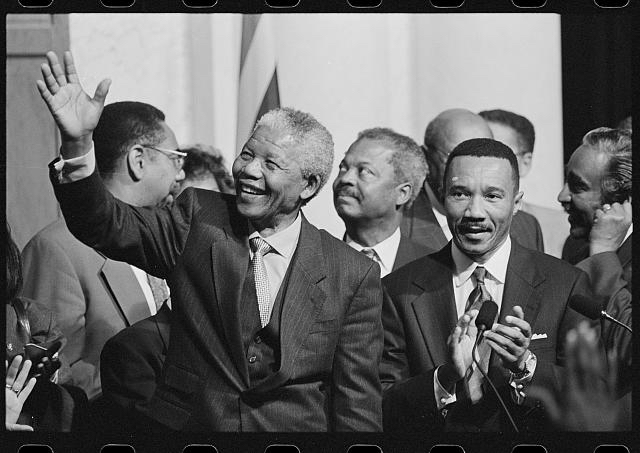

Nelson Mandela, then President of South Africa, with members of the Congressional Black Caucus including Rep. Kweisi Mfume (right) at a 1994 event at the Library of Congress. Behind Mfume are Representatives Donald M. Payne (left) and Charles Rangel (right). (Maureen Keating, U.S. Library of Congress)

Third: Black Americans were never comfortable with Israel’s relationship with South Africa during the time the latter was an apartheid state. South Africa was among the first countries to recognize Israel in 1948. (Russia immediately recognized Israel as well.) There was a community of 120,000 Jews in South Africa in the 1950s and Blacks could not help but notice that these Jews were not at the bottom of South Africa’s racial caste system. They were classified as White. (There is a larger question of whether Jews are in the conventional sense “White” or if it has cost Jews something, as James Baldwin suggested, to accept in certain instances, the classification of “White.”) Israel denounced apartheid but there was diplomatic and military cooperation between the two countries. It should be noted that it was not some leftwing undergraduate or antisemitic professor in recent years who first called Israel an apartheid state. Among the earliest to do so was South African prime minister (from 1958 to 1966) Hendrik Verwoerd who said, “The Jews took Israel from the Arabs after the Arabs had lived there for a thousand years. In that, I agree with them. Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state.” It was not likely to have pleased a lot of Jews to have had Israel characterized in quite that way. And Verwoerd did not do it to show that South Africa and Israel were ideological brothers-in-arms but rather to deflect criticism from his own government. If you are going to criticize me, criticize the Jews too. (This has indeed happened with Israel.) Nonetheless, Black Americans could not have felt exactly as if Jews and Blacks were comrades-in-arms either, after such a statement. After all, the two-state solution was the South African solution to Black self-rule. It was the essence of apartheid. The two-state solution was conceived by both the British and the United Nations as a solution to the problem of the Jewish presence in Palestine with the encouragement of the Zionists. It is the solution de jour. But it is also in some ways the solution of the outcast minority, as Jews are. The White supremacist South Africans were a minority who wanted power over a Black majority. Black Americans, like the members of the Nation of Islam, have advocated for a Black homeland within the United States where, of course, Blacks would be the majority and escape minority status in a White nation. Black Americans started Liberia in the nineteenth century (colonized a portion of Africa, in fact), in part, to have a space where they were the ruling majority. The Jews, a minority everywhere with an unrelenting history of persecution, would want a state where they were the majority, not at the mercy of another people.

South Africa and Israel grew closer in dramatic stages after both the 1967 Six-Day War and 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Israel’s relationship with Black African countries collapsed and Zionism was stamped as a form of racism by the United Nations (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 adopted November 1975).4 Solidarity with Black Africa, with Arab Africa, and the cause of destabilizing South African apartheid, also boosted Black America’s anti-Israel sentiments. An interesting example symbolizing this solidarity is Shirley Graham Du Bois, widow of W. E. B. Du Bois. She was a communist (as was her husband before the end of his life) who died in China in 1977. She wrote a glowing young adult biography of charismatic Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser entitled Gamal Abdel Nasser: Son of the Nile, published in 1972 that intimated a marriage between Arabic and Black Africa, and was certainly anti-Israel. For instance, she included in the text a 1956 poem entitled “Suez” by W. E. B. Du Bois, lauding Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal and Egypt’s defiance of the western powers.5 (Both W. E. B. and Shirley Du Bois failed to give Eisenhower sufficient credit for stopping Israel, Great Britain, and France from returning the Suez Canal to colonial control.) Graham Du Bois had lived in Cairo for a time and knew Nasser well enough to have dined with him on a few occasions. Nasser made more effort to reach out to Black Africa than any other Arab leader had done.

I was reminded of this relationship between Israel and South Africa—each country became a popular vacation destination for the other—by more than one Black person during my undergraduate and graduate school years and especially during the years of the Divestment in South Africa movement. The Jews, in their treatment of the Palestinians, had become Afrikaners, in the minds of many. When Nelson Mandela, freshly released from prison, told a wildly cheering mostly Black audience in 1990 on ABC’s Nightline that Yasser Arafat, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, and Fidel Castro “support our struggle to the hilt,” that is, the struggle to end apartheid in South Africa, it was almost as if Israel had been condemned, to use a popular phrase, to the wrong side of history. Mandela made it clear that Arafat may be an enemy of Israel, but he was no enemy of mine. It was a re-inscription of a colored World, of Bandung all over again. It was as if, with Mandela’s stature as a warranty for the Blacks in the room, that Israel was some misplaced, misbegotten western appendage in the Third World. This is the Mandela as his grandson describes him here.

But the Jewish press offers a more nuanced view, if more favorable to their cause, here and here. Mandela never said that Israel should not exist, never opposed Zionism, and never said Israel should not defend itself. He also accepted an honorary degree from Ben-Gurion University. His first employers in South Africa when he began his law practice were Jews. Let us say Mandela offered three loud cheers for the Palestinians but two smaller cheers for Israel. Let us call it splitting the revolutionary difference.

During my second trip to Israel, I asked our guide, a personable young secular Jew, if he feared that Israel, with the rise of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement in the United States and Europe, would become a pariah state as South Africa had. “Yes,” he said, “I fear it greatly. I don’t think Israel is getting its message out very well. I can’t understand how liberals and the left in America can hate us so much.” He felt that the liberals and leftists in America who hated Israel were simply looking in a mirror and hating what they saw and projecting onto Israel. Their hatred of Israel was western self-loathing. I thought he was right.

Richard Wright was right in using the term underdogs to describe the gathering in Bandung in 1955. A moral and political ideology surrounding the “colored” underdog has emerged in the West. Palestinians are the underdogs, oppressed in the ghettos of the West Bank and Gaza, seething with justifiable resentment at people they feel are expansionist settlers. The Jews have a long history of enduring persecution and oppression, of having been the object of genocide, being exiled, having always been a “suspected” or “unwelcome” minority, but, despite all of this, few think of them today as the underdogs. For many of today’s western liberals and leftists, the Palestinians are North Vietnam. The Israelis are the American imperialist interventionists. Perhaps the bloody October 7 terrorist attack was the Palestinians’ version of the Tet Offensive. In this imaginary tale, the Israelis may wind up winning the battle militarily but losing the propaganda war in the West. This strategy worked for Ho Chi Minh. History can repeat itself with different actors. The anti-western underdog prevails.

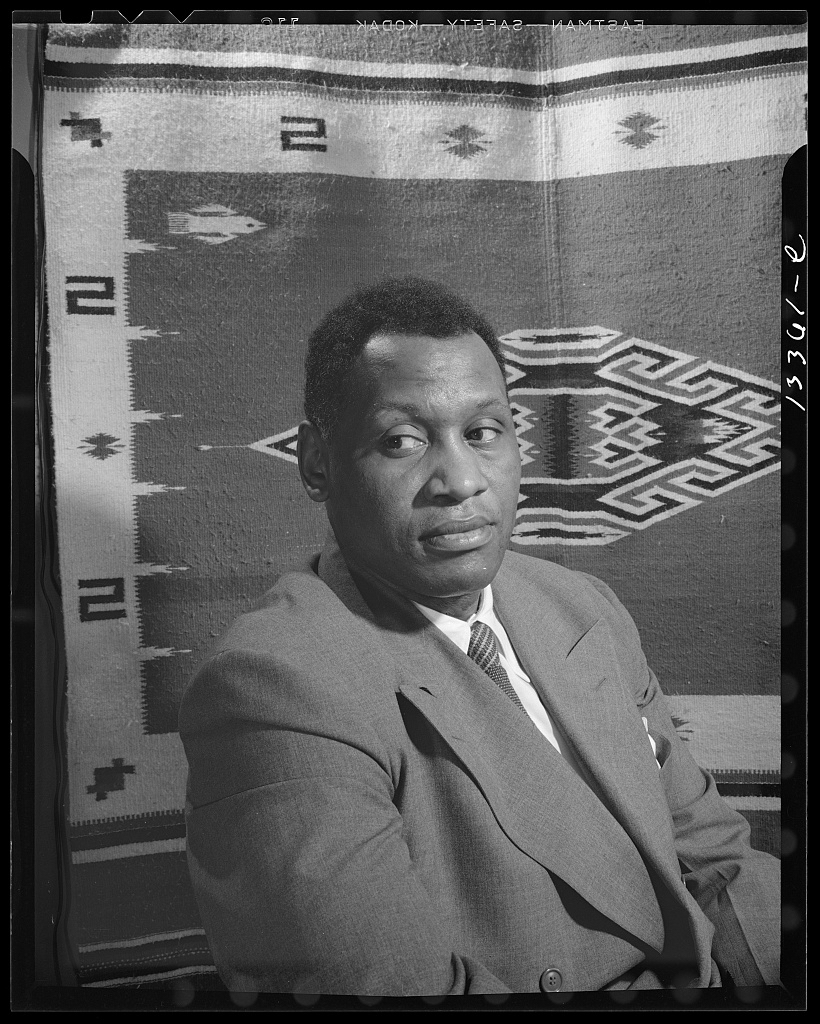

Paul Robeson in a 1943 photograph. (Gordon Parks, U.S. Library of Congress)

3. Paul Robeson has a nervous breakdown

I am a friend of Israel, not of the oil interests.

—Paul Robeson, “I, Too, Am American,” Reynold’s News, February 27, 19496

Gradually I became aware of the Jewish problem of the modern world and something of its history. In Poland I learned little because the university and its teachers and students were hardly aware themselves of what this problem was, and how it influenced them, or what its meaning was in their life. In Germany I saw it continually obtruding, but being suppressed and seldom mentioned. I remember once visiting on a social occasion in a small German town. A German student was with me and when I became uneasily aware that all was not going well, he reassured me. He whispered, “They think I may be a Jew. It’s not you they object to, it’s me.” I was astonished. It had never occurred to me until then that any exhibition of race prejudice could be anything but color prejudice.

—W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto” (1952)7

On March 26, 1961, after a concert performance in Moscow, actor/singer/leftwing activist Paul Robeson locked himself in his hotel room and slashed his wrists. There have been several reasons offered for Robeson’s attempted suicide, particularly doing so in the Soviet Union, a country whose political and social system he had long lauded. Robeson, due to all the persecution and racist opposition he was enduring in the United States, was certainly paranoid, no less so after the strange death of Pan-Africanist Congolese leader and anti-colonialist Patrice Lumumba in January. His biographer, Martin Duberman, writes that Robeson was suffering from “a bipolar depressive disorder that fed on political events …” He dismisses the notion that Robeson was disillusioned with the Soviet Union.8

I had no idea what it [“Occupied Palestine”] meant. It almost seemed hip to utter it, as if someone had some secret revelation about the crimes of this world.

But Robeson was in fact burdened by having been an apologist for Stalinism, even when he learned what Stalinism truly was. One theory about Robeson’s attempted suicide is that during his 1961 visit to Russia, he met with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and asked whether the reports in the western press about Russian antisemitism were true. Khrushchev supposedly was deeply angered by the question and told him he was interfering in Russia’s internal affairs. Khrushchev’s anger dismayed Robeson, who was moved to ask the question because of the murder of some Soviet Jewish friends of his that had bothered him for several years, as they had told him of widespread purges against the Jews under Stalin. Duberman gives an account of Robeson’s 1949 visit to Russia where he learned firsthand from a Jewish friend about the persecution of Russian Jews and the murder of one of Robeson’s Jewish friends by the Russian secret police. At the concert Robeson gave subsequent to learning about his friend’s murder, he gave an especially moving rendition of “Zog Nit Keynmol,” the Warsaw Ghetto resistance song. Why did he do that? When he returned to the United States, Robeson denied he knew of any antisemitism in the Soviet Union.9 Robeson knowingly palmed off disinformation. This kind of cognitive dissonance is not a sign of a man who was disillusioned and wanted to hide it from himself?! Might his attempted suicide have been partly related to having borne the burden, the guilt, of knowing about the persecution of Jewish friends in Russia but refusing to speak out about Soviet antisemitism in fear that it would aid fanatical, racist American anti-communists in their condemnation of what he thought was humankind’s last, best hope on earth? He betrayed his Jewish friends for a larger cause that turned out to be an empty promise. At a certain point, twelve years later in this case, that might give somebody a breakdown for sure. Duberman addresses this theory in a footnote and does not dismiss it out of hand, citing the source as at least partly credible.10 It is a fact that learning of Soviet antisemitism unnerved him. He felt close to Jews throughout his life and saw them as his closest supporters and allies. They were there for him at the Peekskill riot, and he was always grateful for that.

4. Give Peace in Our Time, O Lord

One always has to pay to belong. …

–Masha Gessen, Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region

In the last year or so, three Black celebrities have been accused, in many quarters and not without reason, of being antisemitic. Musician Kanye West praised Adolph Hitler, denied the Holocaust, and praised Nazism on Alex Jones’s Info wars in 2022, losing a number of endorsements. West had been uttering antisemitic stuff for years. Basketball star Kyrie Irving tweeted support for West’s 2022 statements and, finally, was forced to apologize. Most germane is comedian Dave Chappelle who, during a recent stand-up performance, allegedly expressed support for the Palestinians and his disapproval of an occupying Jewish state. (It seems that he actually condemned both sides.) Many of his Jewish patrons walked out but other customers cheered Chappelle. American Jews have always been concerned with Black antisemitism. Undoubtedly, the reason for trips to Israel, such as the ones I went on with a Black contingent, was because of Louis Farrakhan and his constant Jew-baiting in the 1990s, which elevated him in the Black community more than he deserved. But this anxiety over Black antisemitism, especially with Farrakhan, probably did more to hurt Jews in the Black community than to help them. Another intense dust-up between Blacks and Jews occurred during the Ocean Hill-Brownsville conflict in 1968 over the issue of Blacks exercising control over schools where the teachers were predominantly Jewish. In the 1990s, neo-conservative Jews were among the most vocal critics of affirmative action. Richard Herrnstein, the co-author of the 1994 pièce de résistance treatise against affirmative action, The Bell Curve, was Jewish. In these instances, Jews put a certain kind of pressure on the relationship that Blacks did not like, as it felt to them that Jews wanted a demonstration of, well, loyalty to the worth and significance of the relationship, of what Jews had done, and, in all justice, had paid at times, in their support of Blacks. The lack of parity in the relationship made that demand of loyalty seem unreasonable to Blacks. As a point of pride, if nothing else, Blacks felt that they could not submit to that pressure. Indeed, from the Black perspective, Blacks may feel they have a special right or duty to criticize Israel and by extension Jews without necessarily being thought antisemitic. Without Blacks how much would social change have advanced in the United States that has benefited everyone, including Jews? Blacks, in this regard, were the shock troops for the Jews in America because Jewish immigrants here were not Black. In some ways, the presence of Blacks in America enabled Jews to be White. The Jewish perspective, which I understand, expressed a certain vulnerability that Jews felt that Blacks could assuage which is why, in some ways, Jews felt they needed Blacks because we were the only significant, surviving group to know the worst the country had to offer. There was something about this outreach, clumsy as it was, that was actually touching. We Blacks, while we criticized Jews for becoming White in America, were the only people who could testify that they were not White as other White Americans were. They were different and the difference mattered. There is something admirable about the times when Blacks and Jews have tried to reach beyond being prisoners of their experience to reach one another. And something painful about the failures.

There have been Blacks who support Israel in the latest war with Hamas, such as boxer Floyd Mayweather and New York City Mayor Eric Adams. There are so-called Black conservatives like John McWhorter and Glenn Loury who also support Israel but not without some qualifications. How Blacks divide over the latest Arab-Israeli war will matter to some degree to American Jews. Will most Blacks side with Palestinians, seeing Jews as White colonizers, interlopers in Palestine since they first began buying land there in the nineteenth century, oppressing a people of color? Their need for a state comes at too high a cost in blood and dislocation. One line of thinking is that the Jews are arrogant and racist to think that they should have Palestine. Or will most Blacks side with Israel because those who are Christian among us believe that the Jews are truly the chosen people and that the resurrection of Israel is part of God’s plan or because of our familiarity with American Jews, people we have had a considerable and at times deeply personal interactions with? Will Blacks think that the current rise in antisemitism around the world shows Jews truly need a state of their own, for there are too many people who think Jewish lives do not matter?

Neoliberal philosopher Pascal Bruckner writes in The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism (English edition, 2010):

… the true Jew now speaks Arabic and wears a checkered Keffiyeh, while the other one is an imposter who claims title to land and has lost “the moral magistracy of martyrdom. . .” The ancient victim has become the torturer in turn, but—and this is the interesting detail—a torturer who reproduces exactly the characteristics of his former tormentor in 1930s Germany. In short, when Jews oppress or colonize, they are immediately transformed into Nazis; there are no half-measures. . .. In Europe, the Palestinian question has quietly relegitimated hatred of the Jews. Here we can certainly agree with Bernard Lewis when he says that for many of their supporters, “the Arabs are in truth nothing more than a stick for beating the Jews.” (67, 70)11

Bruckner’s observation is worth thinking about. People are always trying to find ways to get out from under their guilt. Is the Palestinian simply a tool for Europe, for guilty White westerners, to get out from under the guilt they feel about their persecution of the Jews? If that is true, it is too bad for Palestinians and worse for Jews. Neither is human in this scenario. Blacks, because of our experience, should bear that in mind even more so than other Americans might. We know what group hatred is as the Jew does and we know what it is like to be used as a cudgel by the “good White people” against the “bad White people” as the Palestinians are being used right now. But were Jews ever really White? On my first tour of Israel, an Israeli scholar told me that the worst thing to happen to European Jews in America was assimilation and “being blended,” as he put it. On both tours of Israel, our hosts had us meet Beta Israel—the Ethiopian Jews, Israeli Arabs, the Druze, a Black American Hebrew group. They wanted us to know that Israel was a multi-racial society.

There is something admirable about the times when Blacks and Jews have tried to reach beyond being prisoners of their experience to reach one another. And something painful about the failures.

One of the highest honors a Black person can receive in America, the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, is named after a Jew. W. E. B. Du Bois was so pleased to have the award named for his closest friend, Joel Spingarn.12 There is something compelling about that for both Blacks and Jews. I hope the reward will always remain named as it is. The Black people who have won it are so inextricably bound in my mind with the name of the medal, with the medal itself. I cannot think of the award in any other way except as one of those nice moments of bonding between Blacks and Jews. I guess I am proof that people truly are prisoners of their own experience.