The first time I saw The Legend of Boggy Creek, it was in a proper theater. There was no option: TV had only the Big Three networks and an early form of PBS, and 1972 was the year deregulation finally led to HBO, the first real cable. Betamax was three years in the future, Blockbuster 13. Streaming was what your nose did during a cold.

My mom took me and my best friend to see Boggy, which is about a seven-foot Bigfoot terrorizing a village near Texarkana.

“I was seven years old when I first heard him scream,” the narrator begins. “It scared me then and it scares me now.”

Eric was cleaning his glasses during the key scene, when a man sitting on the toilet thinks he sees something out his screened window. At the jump-scare, Eric threw his glasses in fright, and they clattered to the floor. I do not remember us laughing as we felt around under the seats.

Recently my younger son, who is 13, went with me to see the world premiere of the digitally-remastered The Legend of Boggy Creek, in the theater in Texarkana where it first showed in 1972.

“You thought this was scary?” he said incredulously after the credits. He laughed. “You warned me about it.”

Boggy looks and sounds to me now like a Disney nature film, so it seems strange Eric and I were its victims. In our defense, we had never experienced internet, video games, or horror movies. Our small town was full of ghost stories and a repressed history of mayhem and mutilations, and Fouke, Arkansas, the setting for the “actual events” of Boggy, was down the Mississippi Valley from us. Boggy Creek chimed with “boogeyman” in my kid brain.

We also spent summers outdoors and knew how deserted the woods and strip mines could be, how quiet it got in the countryside after dusk. There were no cell phones to call for help or to check in; no GPS; no access to weather radar; no medevac. In our relation to the natural world we may have been among the last innocents.

The experience we had in that theater, with its big screen and public spectacle, mimicked something of life: Even when you banded together, something monstrous could happen.

• • •

As a kid in the ’60s, I thought the Patterson-Gimlin footage (1967) of a purported Bigfoot slouching along, looking over her right shoulder, was as significant as the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination. There were similarities.

Both were shot in grainy 8mm and were so brief they were counted in frames, like individual works of art. Both were made possible by smaller, cheaper technology. (No news camera was trained on the Kennedy procession at the time of the murder, any more than on the Archduke’s in Sarajevo. But amateurs had the gear in 1963 and could decide for themselves what was significant.)

Both films became famous immediately and were no longer just “home movies,” “typically meant to be viewed by close family and friends, rather than exhibited in public,” as the Texas Archive of the Moving Image puts it. (Let us pretend the Bigfoot footage was not made cynically.)

These snippets of dreamlike consciousness, one by some guy in Northern California, just off the horse he rode in on, the other by a dressmaker hoping to glimpse Camelot as it rolled past in its carriages, showed more than their makers intended.

As a kid in the ’60s, I thought the Patterson-Gimlin footage (1967) of a purported Bigfoot slouching along, looking over her right shoulder, was as significant as the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination. There were similarities.

Call them Everythem films: Outward-gazing, not domestic; anonymous but with an intimate perspective; private but part of the zeitgeist; amateur but all the more powerful by their democratic implications. Other people shot that footage, but together we took their places, shocked to the point of shakiness because the unthinkable became veritable. Both films forced you to think the world was not as you thought it to be.

“We like to feel that the world is safe,” Errol Morris told Smithsonian Magazine in a discussion of the Zapruder film. “Safe at least in the sense that we can know about it. The Kennedy assassination is very much an essay on the unsafety of the world. If a man that powerful, that young, that rich, that successful, can just be wiped off the face of the earth in an instant, what does it say about the rest of us?”

What would it say about our place as Hominid-in-Chief if Bigfoot walked onto our porch at night and judged us through the window?

• • •

Before Boggy there were other cryptid-hominid movies, such as The Snow Creature (1954), Half Human (1955), The Abominable Snowman (1957), and Bigfoot (1970), with John Carradine. There have been dozens of Bigfoot movies and TV shows since.

But Boggy was the first of them to use the docudrama format, which mimics the Everythem ethos with its real locations and first-person views. It was itself an influence on later exploitation and independent films. “There would’ve been no Blair Witch without Legend of Boggy Creek,” Eduardo Sanchez, co-director of The Blair Witch Project, has said.

Maybe due to that format, Boggy felt like a private experience to me, and I have been surprised how many remember it. Sources say it was the 9th or 11th highest-grossing film of 1972, the year of The Godfather and The Poseidon Adventure. It made $25 million on a $160,000 budget.

Also, like an Everythem film, Boggy seemed almost accidental. In the mid-1960s, its future director, Charles B. Pierce, was the art director at the NBC affiliate in Shreveport, Louisiana. Later he was the weather guy, and played Mayor Chuckles on The Laughalot Club. In ‘69 he moved to Texarkana and started an ad agency around work he got from a company that built tractor trailers and farm equipment.

Boggy was the first of [the Bigfoot movies and TV shows] to use the docudrama format, which mimics the Everythem ethos with its real locations and first-person views. It was itself an influence on later exploitation and independent films. “There would’ve been no Blair Witch without Legend of Boggy Creek,” Eduardo Sanchez, co-director of The Blair Witch Project, has said.

But Pierce was a ringer. He not only shot ads for Ledwell and Son Enterprises but was able to talk L.W. Ledwell into providing $100,000 of Boggy’s budget. Pierce had already worked as a set decorator on 15 TV series and films, including Waco, with Howard Keel and Jane Russell. Growing up in Arkansas, he and friend Harry Thomason shot movies with an 8mm camera. Thomason would become Director and Executive Producer of Designing Women and Evening Shade.

Pierce also had a talent for finding talent. The actors in Boggy were locals, authentic and cheap, recruited at a gas station or asked to recreate events they had experienced. High-school students served as crew.

Pierce knew writer Earl E. Smith from advertising and had him write the screenplay from eyewitness accounts of the Fouke Monster. Smith had done training films for the US Navy with composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava, who worked on the 1950s Disney television shows the Mickey Mouse Club and Zorro. Mendoza did the soundtrack and introduced Pierce to Tom Boutross, who had been a film editor for Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. Mendoza also knew artist Ralph McQuarrie, from work they did for CBS during the Apollo program, and McQuarrie illustrated the Boggy movie poster, his first. (McQuarrie would do the concept paintings for Star Wars and most of its major characters, even as he worked with Pierce on other B-movies.)

Pierce’s Art Director was John Ball, who later worked for Hallmark and created Shoebox Greetings, according to Pierce’s daughter. Ball made the monster costume from a rented gorilla suit and wigs.

Tommy Clark, who handled the production’s money, said at the premier that they could not find distribution. They “finally scraped up the money to buy four prints,” Clark said, and were showing Boggy in Texarkana, Tyler, and Longview, Texas, and in Shreveport. People lined up for five blocks in Texarkana to see it; that theater alone made $55,000 in a month.

There were no percentage deals then; they also had to pay for theater time in advance and recoup it from ticket sales, Clark said. A regional theater-chain owner, Joy Houck, Sr., realized he was making a killing on popcorn from Boggy in his Shreveport theater and offered to pay for prints to put it in national distribution. The deal made Pierce a millionaire.

Pierce and Earl E. Smith did six more low-budget films directed by Pierce and co-wrote Clint Eastwood’s Sudden Impact. (Pierce is often credited with the line, “Go ahead, make my day.”) Pierce made 13 films over 26 years and worked with Slim Pickens, Jaclyn Smith, Lee Majors, and Peter Fonda. Mystery Science Theater 3000 had a lot of fun with his Boggy Creek II: The Legend Continues (1984), which Pierce was pressured into making and considered his worst movie. (He stars in it.) He stopped directing in 1998 but continued to work as set decorator on MacGyver, Remington Steele, and other TV shows. He died in 2010, at 71. His legacy is mixed but was leaning into oblivion.

• • •

Now, The Legend of Boggy Creek, in its 47th year, has been remastered by Pierce’s daughter Pamula Pierce Barcelou. The restoration was done by Film Preservation Services, at the George Eastman Museum Digital Laboratory, in Rochester, New York. Pierce Barcelou said film restoration cost $15,000; another $15,000 went for audio restoration with Audio Mechanics, which works with major studios and on other film preservation efforts. The remastered Boggy is in 4k, a standard high-resolution format, and will be released on Blu-ray in the fall.

My son and I drove down to the premiere in Texarkana, where it all started. Highway 30 from Little Rock was packed, and giant CAT forest machines were chewing up the median, leaving piles of bundled trees and hills of sawdust 25-feet high and 100 long.

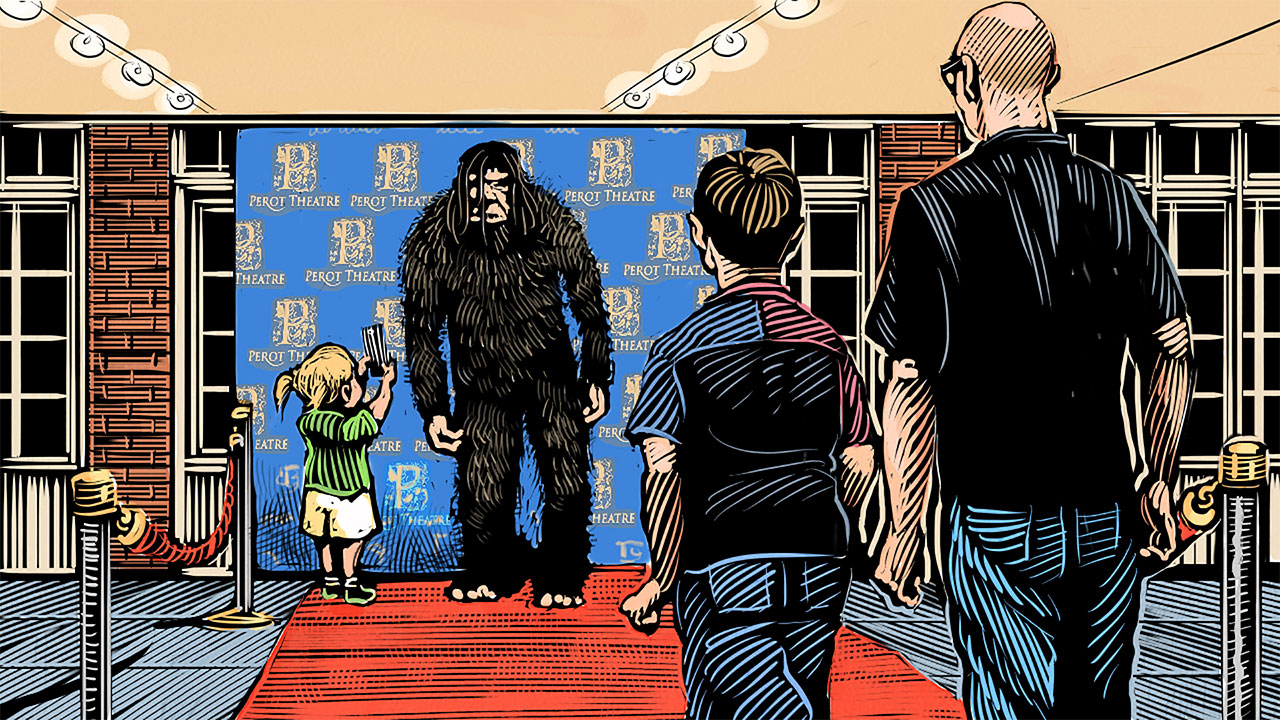

A banner of the McQuarrie Bigfoot hung on the Perot Theater (yes, that Perot), which is on the National Register and once hosted Annie Oakley. Someone in a Bigfoot suit posed with theater-goers out front, careful not to touch them.

Organizers hoped for a sellout, but the theater was half-full. Going by their chatter, accents, and cowboy-premiere dress, most were locals. The woman at Will Call thanked me profusely for coming so far, and the t-shirt vendors were engaging and sweet. I had a paranoid sense the whole town was in on it, until I asked an usher who the dude in all-black clothes and a stampede hat in the lobby was. He looked like a roadie.

“I don’t know, but he’s been walkin’ around like he owns the place,” she said.

This was Lyle Blackburn, author of The Mothman of Point Pleasant; Momo: The Strange Case of the Missouri Monster; Lizard Man: The True Story of the Bishopville Monster; Monstro Bizarro: An Essential Manual of Mysterious Monsters; and most importantly, The Beast of Boggy Creek: The True Story of the Fouke Monster, considered the definitive book on the movie and Texarkana sightings. He is also frontman and founder of the band Ghoultown.

Blackburn introduced the screening. He spoke well but had the seriously-dead stare of a man who has lived through too many Comic-Cons where strangers demanded truth about the Lizard People. He said he grew up three hours from Texarkana and saw Boggy at the drive-in, which was his parents’ way of not hiring a babysitter. They thought he would sleep through the movie, but it began a career. He said people everywhere tell him they saw the movie as kids too, and “it scared the mmm out of them.”

• • •

The movie started, to cheers from the audience. I had mostly forgotten or misremembered it. It opens in the Sulphur River bottoms with shots of animals, a strangely upbeat song, and an avuncular voiceover, exactly like Walt Disney nature documentaries and “adventure family films,” such as Charlie the Lonesome Cougar.

Boggy was shot in Techniscope, which Roger Ebert said was “a process designed to give a wide-screen picture while saving film and avoiding payment of royalties to the patented processes like Panavision. […] Techniscope causes washed-out color and a loss of detail.” The film stock was used by low-budget directors, or when a “gritty” look was needed to hint at documentary, as with American Graffiti. It does help establish the Everythem mood and reinforces Pierce’s choice never to show the monster distinctly.

There are no developed characters and no plot. The movie is a series of disconnected sightings with few consequences. Two shoats go missing, some flowerpots are smashed, a cat dies in kitschy fright, and one man goes into shock but revives without explanation. More than once a chair under a doorknob keeps out the monster.

Any tension comes from Pierce’s nod to primal fears: rural desolation and poverty; the sun setting behind darkening woods; an inhuman wail of anger or grief; cattle and dogs reacting to something unseen.

The movie also shows sympathy for the monster, which is confusing, given how he is demonized. Voiceover says he feels the “lure of civilization” in his “lonely frustration.” One of the songs (written by Earl Smith) says, “Perhaps he dimly wonders why / There is no other such as I / To touch, to love before I die / To listen to my lonely cry.”

The movie is so dated and mannered it is impossible to watch innocently now. What was on the minds of Texarkanans in the early ’70s, to obsess over rumors of a monster then make a movie about it and play themselves? What did this fear of an indistinct Other that will not stay in its place correspond to? Because everyone in the film is white—Fouke is still a village of 700 and 95 percent white—it hints at race, but the movie could as easily be read through lenses of internal xenophobia, anxiety over political division, distrust of government or science, or old-school Nixonian paranoia. (All these make the movie ripe for rediscovery now.)

Two scenes involving teen girls or young married women on their own give this lyric a drive-in prurience or, worse, a hint the monster might “bother” them, that 20th-Century euphemism that launched lynchings. Most of the characters have guns and an unwavering confidence in bush justice. The monster is shot (at) many times.

The movie is so dated and mannered it is impossible to watch innocently now. What was on the minds of Texarkanans in the early ’70s, to obsess over rumors of a monster then make a movie about it and play themselves? What did this fear of an indistinct Other that will not stay in its place correspond to? Because everyone in the film is white—Fouke is still a village of 700 and 95 percent white—it hints at race, but the movie could as easily be read through lenses of internal xenophobia, anxiety over political division, distrust of government or science, or old-school Nixonian paranoia. (All these make the movie ripe for rediscovery now.)

The movie’s ambivalence to the monster suggests another possibility. There is “still a bit of wilderness … a bit of mystery left,” the narrator says, relieved, though that equates to future threats. In Boggy Creek II, Pierce says it directly: “He’s a part of nature, living in harmony in one of America’s last great wildernesses. That’s why this legend will continue.”

Bigfoot is Nature, or what is left of it. “[I]t seems incredible the creature is still out here,” the narrator says. “Maybe you don’t believe the story.”

“I don’t,” a woman in the audience said loudly, and we all laughed.

• • •

“That was the worst movie but the best movie I’ve ever seen,” my son said. He admitted the scene with the monster’s hand reaching in a window “barely got me.”

Afterward the Fouke mayor read a proclamation that said, “The great city of Fouke is forever in debt” to Charles and Pamula Pierce, and that July 15, 2019, would be Charles B. Pierce Day, “for his genius mind.” Not to be outdone, the Texarkana mayors proclaimed jointly their own Pierce days in June.

A panel followed the screening. Six of the original actors (plus Pamula Pierce Barcelou, who was also in the film) were there, as was the first cousin of another actor, the movie’s business manager, and its composer’s two children.

“Oh good gracious goodness,” Jinger Hawkins Rausch, who played one of the teen girls in danger, hollered. “That monster has haunted me longer than my marriage lasted.”

During Q&A, Mark Rapp, director of an independent zombie movie called Biophage, got applause for coming from Pennsylvania. His voice shook as he thanked Pierce Barcelou for the restoration, and her father for “influencing people like Lyle, like me, in hidden animals, cryptozoology.”

“It’s our hope as artists to leave legacies, not just for our kids,” he said. “We want to make the world a little bit better—a little bit more interesting at least.” He asked Pierce Barcelou for personal memories of her father that would serve Rapp as “a creative with a daughter.”

“Oh good gracious goodness,” Jinger Hawkins Rausch, who played one of the teen girls in danger, hollered. “That monster has haunted me longer than my marriage lasted.”

Pam said her dad was “probably the funniest person I’ve ever been around” and “very charismatic.” People called him “Sparkplug” for his energy. She first heard of the Fouke Monster in second grade, when kids were talking about it in the cafeteria, because it was in the newspaper that morning.

“The next thing I remember is my dad telling my mother that he was going to make a movie, and it was going to be about Bigfoot, this creature. I was at the top of the stairs and heard him talking, and I remember eavesdropping on my parents. My mom was very calm and said, ‘Yeah, I think that’s a great idea.’ And so the next thing I remember was my dad sitting on the floor of our apartment living room, and he had the manual for the camera, and he was assembling the camera and reading the directions. So that’s how much of a newbie he was.”

When the film was immediately successful, he bought himself a Corvette, she said. “He would stuff his three children into the back of the Corvette, and drive from here to Shreveport every night to pick up the receipts.” She fell asleep in the back of the theater while he waited for the box office to release his money, then they drove back to Texarkana.

“Always, with my father, if we were awake, he would slow down the car and act like we were running out of gas at Boggy Creek,” she said.

• • •

The next day we stopped in Fouke for the annual Monster Festival, with its “guided bus tours, food, vendors, and presentations by some of the top Bigfoot researchers in the field.” The town museum, community center, and grounds were swarming with movie fans and cryptozoologists, as was Monster Mart, a one-pump gas station that sold Bigfoot-themed snacks, t-shirts, knickknacks, and books.

Fouke’s Recorder-Treasurer told me how to get out to Boggy Creek, beyond the edge of town. My son and I passed “No Hunting No Trespassing” signs, and one that read, “Smile, you’re on camera.” I parked near the purling creek. My son said he “really, really hoped” we would see something. We took photos and talked until a pickup and trailer loaded with lawn gear blew by, throwing gravel. I waited a few minutes more then stared into the rearview for my son’s benefit, shouted, Oh No! Here it comes!, and we peeled-out for home.

The floodplain outside Fouke was denuded by machines. Google Maps sent me down a narrow road through a forest, and for 40 miles our right wheels wobbled in the rut made by logging trucks. I thought of how I should have rented a Bigfoot suit and had a friend run across the road, so I could brake hard and point to him disappearing in the trees. It seemed the least a parent could do, restore some wildness to the world.

• • •

Things were different in my day, I tease my kids, but it is true. There are now 30 million surveillance cameras in the United States, 250 million smartphones, and nearly 400 million guns. If Bigfoot existed, he would be shot, one way or another.

Humans have long seen nature as a monster. We have tried our banded-together best to destroy it but cannot stop thinking about creatures that never stood a chance against us. The idea of a seven-foot hominid wandering around Texarkana, or the Pacific Northwest, or the Himalayas, is an aftertaste of our fear and hope that such things are still possible.

Things were different in my day, I tease my kids, but it is true. There are now 30 million surveillance cameras in the United States, 250 million smartphones, and nearly 400 million guns. If Bigfoot existed, he would be shot, one way or another.

Since Eric and I saw Boggy, the human population of the earth has doubled, while the rest of the animal kingdom’s vertebrate population dropped an average of 60 percent. The Greenland Ice Sheet, world’s second-largest freshwater reservoir, has lost 4,976 gigatons of water to Anthropic warming. (A gigaton is one billion metric tons.)

The bones of creatures we can hardly believe existed fall from ice cliffs into the sea. Goodbye, Monster, goodbye, we wail, our smartphones aimed at a real horror.