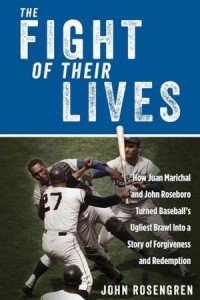

The Fight of Their Lives: How Juan Marichal and John Roseboro Turned Baseball’s Ugliest Brawl into a Story of Forgiveness and Redemption

Readers with knowledge of baseball history may know of the fight between hall of fame San Francisco Giants pitcher Juan Marichal and Los Angeles Dodgers catcher John Roseboro that left Roseboro with a deep gash on the top of his head and over 14 stitches. Anyone watching footage of Marichal turning toward Dodgers’ catcher John Roseboro and viciously striking him in the head would convict the man—no questions asked. So why bother reading about a fight between Marichal and John Roseboro, which became the most memorable moment in the history of a National League pennant race that occurred nearly 50 years ago? What else is there to tell? Over 42,000 spectators and millions of television viewers saw what happened. Visual images have a profound effect on perception. The live game and infamous photo of Marichal holding a bat in his hand after striking Roseboro is the “truth” people remember and know. However, John Rosengren’s book The Fight of Their Lives: How Juan Marichal and John Roseboro Turned Baseball’s Ugliest Brawl into a Story of Forgiveness and Redemption distills obscure facts, details, and forgotten history culled from interviews with players and research to alert the world that there is much more to this story that has not been divulged.

The cliché, “nothing exists in a vacuum” is quite appropriate when considering the Juan Marichal and John Roseboro altercation of 1965. Author John Rosengren meticulously reconstructs their lives to make this point. Over the course of a prologue and ten chapters he outlines a litany of factors leading up to the moment that altered both men’s lives forever, making them mortal enemies, then fast friends.

The Fight of Their Lives is equally a story about the prejudice against Latinos and blacks and American culture in general during the 1950s through the 1970s. Indeed, the fight is a minor focus of the story. For example, the first four chapters alternate between John and Juan’s stories as young men and their paths to professional baseball; the fight is not mentioned until chapter six. Rosengren constantly nudges readers to realize both men do not exist in a vaccum—void of any connection to other people, traditions, or social factors. Thus, chapter five is titled “Summer of Fury” to make the reader privy to the Watts Riots that erupted a few weeks earlier and to serve as a reminder that the 1960s was an intense, unique decade in American history, fraught with declarations of redefinition that created social turbulence that forged dramatic social reforms in the United States. This is a story of heroism, cowardice, miscommunication, racism, the 1960s, and reconciliation. It is about much more than a fight.

It is the tale of interwoven individual histories whose disparate strands shed a renewed light on a historical event we previously thought we knew. By delicately and objectively pulling apart a previously tightly woven tale of a Latino gone mad, Rosengren effectively reinscribes “the incident.” His book is an act of re-memory, which like neo-narratives are strategic historical reflections that enrich history, that tell new stories. In literature and history re-memory is a unique phenomenon. It changes none of the facts but manages to provide insights lost in the more general telling of history. Re-memory humanizes moments and subjects, complicating the known with previously overlooked details and factors, making the past unfamiliar and new. Toni Morrison famously achieves this in her novel Beloved to explore why a woman’s decision to kill her child rather than allow her to endure life enslaved might not be an act of murder. The exercise and objective of “re-memory” projects is to force us to see what we think we know of the past through a different lens for a more objective recollection.

Similarly Rosengren seeks to peer into the humanity of the men involved in the fight. He culls facts—known, unknown, and forgotten—from both men’s lives from their childhoods, as minor league players, as professional athletes, and as black men living and working in late 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s America, making the men familiar to readers before recounting the incident in chapter six. Rosengren further contextualizes the fight by reminding the reader that not only were the two men part of the “nation’s oldest rivalry in professional sports” but that “Violence always lurked when the Giants and Dodgers played dating back to the first encounter in 1889;” and that long before Mariachal and Roseboro stepped on the diamond there was conflict between the teams, which continues to this day!

The cliché, “nothing exists in a vacuum” is quite appropriate when considering the Juan Marichal and John Roseboro altercation of 1965. Author John Rosengren meticulously reconstructs their lives to make this point. Over the course of a prologue and ten chapters he outline a litany of factors leading up to the moment that altered both men’s lives forever, making them mortal enemies, then fast friends.

In fact, the first matchup between the Dodgers and Giants was overshadowed by “The specter of violence” making what happened in 1965 not that unusual. Rosengren frames an “atmosphere and tradition [that] pushed the players to compete at a higher level.” And this was not the first fight between players. The Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson and the Giants pitcher Sal “the Barber” Maglie grappled in 1951. Then in 1955 Robinson and Giants shortstop Alvin Dark fought when Dark “bowled over Robinson at third base.” The Dodgers’ outfielder Carl “the Reading Rifle” Furillo charged Giants manager Leo Durocher in 1953 when Giants’ pitcher Rubén Goméz hit him on the wrist with a pitch. In recounting this violent history between the teams Rosengren seeks to remind readers that this rivalry was one that inspired intensity that began long before April 29, 1965.

While many may not agree with his argument, the history of violence cannot be ignored. Hall of fame Los Angeles Dodger pitcher Don Drysdale admitted that he “always play[ed] this series just a little harder.” Giants first baseman Willie McCovey says of their visit to Los Angeles in the 1965 season: “When you stepped off the plane in Los Angeles , you could hear the electricity.” His neo-narrative is designed to create the space to allow their altercation to be fully reimagined and realized through less liminal lens than it was previously. And he bolsters this by reminding readers that 1965 was, a “summer of fury” that included the murder of Malcolm X in February of that year, the “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama in March of that year, foreign combat as the United States “sent its first troops to fight in Vietnam” civil war in the Dominican Republic (Marichal’s native land) and residents of Watts rioted in August.

Rosengren’s strategy is to make the incident feel less irrational or blatantly criminal and to force readers to judge Marichal differently given their new knowledge about both men, the rivalry between the Dodgers and Giants dating back to the late 19th century, Marichal’s easy-going demeanor, Roseboro’s seriousness and his protective nature, the political tensions in the Dominican Republic, and American prejudices. The culmination of these factors, Rosengren illustrates, ignites the explosive moment that occurs between Roseboro and Marichal. The incident becomes something of a backdrop to Juan, John, and 1960s America. Rosengren paints a picture of individuals, how they came to be, were nurtured and came together to create the moment when John buzzed Marichal’s ear with the ball and Marichal retaliated with a bat upside John’s head. This new narrative replaces the former image. Rosengren exposes the social tensions—in the United States and Dominican Republic—and the intense pressures of a rivalry dating back to the late 19th century that compelled Marichal to take a bat to a man’s head was not due to an “uncontrollable temper” but fear confirmed by Roseboro’s multiple threats and buzzing Marichal’s ear with a ball.

The book succeeds in building a narrative anchored around two people’s lives rather than two players involved in a horrific spectacle. Instead the story becomes each man’s childhood and their divergent yet parallel paths. For example, readers learn that Marichal endured racist taunts and treatment during the two and a half years he spent in the minors, as did Roseboro. Readers also learn that Marichal’s nickname “laughing boy,” emerged because of the language barriers he faced. Unable to speak English very well there were communication fissures, but he never seemed to complain. He was perpetually smiling in the eyes of teammates and coaches. Known as “Laughing Boy,” Marichal was among the early wave (including outfielder Felipe Alou and first baseman Orlando Cepeda) of dark-skinned Latin American players breaking barriers in the United States a full decade post-Jackie Robinson. And John Roseboro, who emerged from Ohio, was among the black American baseball stars following in Robinson’s footsteps, seeking opportunity in baseball, clearing space for acceptance in one of the most important positions on the field—catcher, having to endure the pressure of following in the footsteps of Roy Campanella, the tragically injured, bi-racial All-Star catcher of the Dodgers who immediately preceded him.

Unwilling to end the story with the fight or the conclusion of their playing days Rosengren follows both men after baseball. Marichal played in the Major Leagues from 1960 to 1975; Roseboro from 1957 to 1970. At the end of both of their careers they struggle on the fringes of mainstream acceptance in baseball. John, after his playing days end, divorced, was homeless for a time, and had a short-lived career as a coach for the Washington Senators and California Angels. He was briefly a catching instructor for the Dodgers in 1987. Juan, despite being one of the most dominant pitchers of his era, is not inducted into Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame until 1983, eight years after he has retired and three years after his initial eligibility to be voted into the Hall. . Probably the fact that Marichal had been overshadowed during his career by Dodger ace Sandy Koufax and Cardinal flamethrower Bob Gibson affected his entry to the hall. For instance, unlike Gibson and Koufax, Marichal never won the Cy Young Award, given annually to the best pitcher Major League Baseball. In 1967, the award was changed so that the best pitcher in both the National and the American League was honored instead of just one pitcher for both leagues. As good as Marichal was, he was never recognized as the best pitcher in the league during his glory years. But surely the altercation with Roseboro also negatively affected Marichal as well. He was vilified despite the excellence he displayed as a pitcher and denied induction on his first two tries. It is at this point that a more important story emerges: Roseboro’s role in helping Marichal’s case for the Hall of Fame. The story of how these two men overcame history, anger, and the forces of rivalry to become friends and to make sure Marichal achieved his rightful place in baseball history is the most interesting aspect of the text. Roseboro personally pleaded with the Baseball Writers Association of America, the body that determines who enters Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame, not to hold the fracas against Marichal. By this time, both men had become good friends.

Rosengren challenges the master narrative of Marichal as the crazy Latino who, on that fateful day in 1965, experienced “a burst of uncontrollable temper [acting] under circumstances still unclear.”[1] This book is reclamation of these men; it is a project that lends itself to acknowledge the complexity of their consciousness and the complex welter of events leading up to the famous brawl. In the end, Rosengren argues that it is an injustice to blame Marichal solely for the altercation, that many factors are responsible for what happened.

Some traditions of extreme rivalry refuse to die. In July 2014, fifty years after Marichal and Roseboro’s infamous fight, a jury found the Los Angeles Dodgers partially liable for the debilitating 2011 beating 42-year-old Giants fan Bryan Stow suffered at the hands of two Dodgers fans, Louie Sanchez and Marvin Norwood, in the parking lot of Dodgers Stadium. The beating, which occurred on opening day of 2011, nearly took Stow’s life. The jury found the Dodgers partially responsible for what happened because the Dodgers failed to offer proper safety in Dodgers stadium, which had become a place of violence and drunkeness. Stow was awarded $18 million of which the Dodgers must pay one-quarter. Sanchez and Norwood are responsible for the remaining amount.