Some writers and readers do not like the term “creative nonfiction” for its implied judgment on other forms. Journalism, after all, has its own problems to solve in its own creative ways.

“Literary nonfiction,” which I prefer, may sound even more elitist. The push to eliminate the gradient of high and low in culture, or even the notion that there is better and worse writing, is based in good intentions: these things tend to serve power. (This model shows that 95 percent of English-language fiction published between 1950 and 2018 was by “white” authors.)

Yet there has been something comic in the shock of those who hoped to decentralize texts after real journalism was labeled fake news, and internet rants, propaganda, and baseless conspiracy theories became ascendant. “This is my truth” can be a tool for anyone, including followers of Q.

Let me suggest from my hut here in Tomis, that literary nonfiction is often but not always up to something different, at least from other nonfiction forms, and that it is trying to get at something more, something that falls in the gap between data and solipsism. But what is that thing?

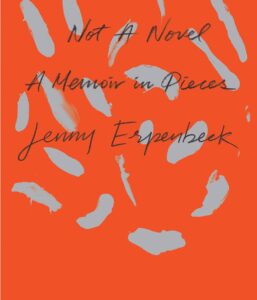

I have seventeen tabs open in my browser and piles of books on my floor—all nonfiction by good writers, ranging from the news of the day to David Graeber on the first 5,000 years of debt. But Jenny Erpenbeck’s Not a Novel: A Memoir of Pieces was the only reading I could concentrate on recently when someone I consider a brother seemed to be fighting for his life.

Like all good literary nonfiction, the book acknowledges the something-more which comforts precisely because, as Erpenbeck says, “we find that things fall by the wayside when we speak [and] strange as it sounds, the most important reason for writing is probably that we are at a loss for words.” (143)

Jenny Erpenbeck, born in East Berlin, is an award-winning German novelist, short story writer, playwright, and opera director. Not a Novel is her first full-sized nonfiction collection, translated in 2020 by Kurt Beals, a professor in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures at Washington University in St. Louis. (Erpenbeck’s earlier, brief, nonfiction collection, Things That Disappear, is excerpted in English here.)

Like all good literary nonfiction, the book acknowledges the something-more which comforts precisely because, as Erpenbeck says, “we find that things fall by the wayside when we speak [and] strange as it sounds, the most important reason for writing is probably that we are at a loss for words.”

Not a Novel collects two decades of award acceptances, addresses, essays, and close readings, as well as pieces more consciously “creative” by their form or language. (In “Hope,” for example, 25 of the 37 paragraphs start with the word “when”—as in, “When my mother was a mother she hoped nothing would happen to me.”) (40)

The book is divided into three loose sections: “Life” (topics such as childhood, East Berlin, the death of Erpenbeck’s mother); “Literature and Music” (opera, Ovid, her own plays and novels); and “Society” (an obituary for an immigrant and a plea for human rights). But Erpenbeck’s main interests are borders, transformations, language, and silence.

“There is nothing better for a child than to grow up at the ends of the earth,” she says in one of the book’s more memoir-like sections. (32) Growing up, she loved East Berlin because it was hers, her community’s. Despite what many American readers might imagine, she says she felt “completely and utterly safe” there.

“As a child I loved the ruins. They were secret places, unoccupied places where the weeds grew up to your knees, and no adults ever followed us there. [. . .] Places where you could look up through several floors and burned-out windows to see the sky. Places where shepherd’s purse grew, with heart-shaped pods that you could eat.” (29)

“As a child you love what you know,” she says. “You are happy to know anything at all. And this happiness takes root and transforms itself into the feeling of being at home. And so, yes, I loved that ugly, supposedly gray East Berlin, forgotten by the whole world but familiar to me. . . .” (37)

The book is divided into three loose sections: “Life” (topics such as childhood, East Berlin, the death of Erpenbeck’s mother); “Literature and Music” (opera, Ovid, her own plays and novels); and “Society” (an obituary for an immigrant and a plea for human rights). But Erpenbeck’s main interests are borders, transformations, language, and silence.

The sensory details she provides, however, often unsettle that sentiment and create tension. In one section, there is a “glass jug on the floor filled with fermenting grape juice that’s supposed to turn into wine, but sometimes it turns into vinegar…a canning jar full of the leeches that my grandmother has to apply to herself to prevent thrombosis. When I spoon out the pear compote for dessert, I look uneasily at the leeches. . . . In my great-grandmother’s bedroom…a lacquered wooden clock with golden numbers ticks throughout my entire childhood. This room . . . is never heated. . . . When I look from the bedroom . . . I can watch the soldiers on patrol . . . then the barricades, the watchtowers, and the wall….” (5).

Leipziger Strasse where she lived had been, 100 years earlier, a “very lively commercial thoroughfare. . . . Jewish textile factories did business in that neighborhood until the early 1930s. But by the time I was a child, all of that was gone, and I didn’t even know that anything was missing—or anyone.” (31)

This inheritance of absence is, she says, “The great misfortune of disempowerment, the great fortune of disempowerment.” (55) It becomes an apologia for her writing: “An empty space is a space for questions, not for answers. And what we don’t know is infinite.” (34)

There were other absences and losses. Shortly after she came of age, the wall came down and, she says, “Our everyday lives weren’t everyday lives anymore, they were an adventure that we had survived, our customs were suddenly an attraction. In the course of just a few weeks, what had been self-evident ceased to be self-evident. [. . .] From that moment on, my childhood belonged in a museum.” (22)

In addition to the unusual losses of country, flag, monetary system, and the businesses in her neighborhood, bought by outsiders and quickly closed, Erpenbeck has experienced the losses we all face, as when her mother died, the apartment had to be dealt with, and the belongings sold, donated, stored, or thrown away.

Her home, she feels, became “a purely mental state [that] will no longer exist anywhere except in the convolutions of my brain and the convolutions of certain other brains. . . .” (24)

Writing serves memory’s responsibility, even if it does not always soften it.

In the book, Erpenbeck identifies two kinds of disappearance and grief. One is for “specific places: the vaccination clinic, the cafeteria, the auditorium. Not for the rooms themselves, of course, but for those rooms as the setting for my everyday childhood experiences, a setting that was slowly rotting away—as if that everyday life, so far in the past, could also grow old and weak in retrospect.”

The other is “for the disappearance of unfinished or broken things…that had visibly refused until now to be incorporated into the whole. . . .”

The emotions of this absence are a mixed curse and blessing, she suggests. Because “the present can’t make its peace with everything,” (27) a larger, though sometimes darker, worldview emerges.

Writing serves memory’s responsibility, even if it does not always soften it.

“. . . I learned to live with unfinished things. . . . [I]t’s possible to live quite comfortably in the bottom two floors of an apartment building even when the top two floors have been bombed to rubble. And that’s the sort of knowledge that you never forget. Even today, without thinking too much about it, I automatically transform all shopping malls into the ruins of shopping malls, I see clouds of dust rising up in luxury boutiques, I imagine the glass facades of office buildings shattering and crashing to the ground, revealing the naked offices behind them where no one is working anymore.”

These visions roll on for a full page, “as if the decay of everything in existence were simply the other half of the world, without which nothing could be imagined.” (30-1)

Living in a split city invited double consciousness. East Berliners could hear and feel the warm breeze through the vents of the West Berlin subway, which ran underfoot but did not stop in the East. Construction noises came over the wall, and there was the sight of “airplanes overhead in which we would never fly. . . .”

“[T]here was a whole other world,” Erpenbeck says. (33) This awareness continued, even after reunification, even after others tried to ignore or forget.

“[T]here can be no discussion of experiences and feelings,” Erpenbeck says, admitting of the difficulties of writing. “They have their own, wholly individual morality, and they lie beyond the knowledge that we later acquire. They are simply there.” (78)

And so, for her, the task becomes making “the thoughts and feelings that I translated into letters . . . capable of being translated back into thoughts and feelings, by readers. . . .” (64)

This is no small feat, she says, even in everyday life: “Indeed, whenever people speak, it fundamentally raises the question of whether words can ever lead to understanding. It was the unresolved and the unresolvable that interested me.” (120)

Speaking of her process (in writing fiction), she uses the word “groping” for finding her way toward what goes on the page: “. . . I lead myself—but the reverse is also true, as it is in every search, I’m led by the thing I’m searching for. So it’s a state in between the knowledge that something is there and the ignorance of what that something is.” (80)

“Every time I start a new work, I ask myself . . . if I’ve ever really known how to write down a sentence…how to look at a story, how it’s even possible to turn the innermost things outward, and then, after stripping off my own skin, to peer through it. Each time, I’ve found that I don’t know anymore.” (65)

Several pages later (69): “It’s not just a matter of what interests you, it’s also a matter of what sort of space takes shape beyond the part that you tell. It’s a question of what need not, or cannot, be said.”

Living in a split city invited double consciousness. East Berliners could hear and feel the warm breeze through the vents of the West Berlin subway, which ran underfoot but did not stop in the East.

“It takes an entire lifetime to unravel the mysteries of our own lives,” she says (31), delineating the scale of the problem. But the method, which does not have to wait for the unraveling, is clear: “[T]he perspective always is the story.” (72)

Underneath the expected use in literary nonfiction of heightened and figurative language, established conventions of form, literary references, and narrative with the texture of fiction, there is perspective: not just a place and time from which to tell a story, or a manner of framing to leave out the extraneous, but in every new piece, a new opening to the material in order to see what is there and what it means. This opening, and the emotions that rise from it, is the story of the story.

Which may be why so much literary nonfiction goes meta or self-critical, and why the writer is often portrayed as participant in the story being told. This writing’s true subject is complexity—the nature of knowing, of memory, of consequences, of body and mind.

Yet the problem exists for us all, daily. Can we say what is true or important, even if we know? “[U]nderstanding is only possible, if at all, when we have a view of the whole,” (164) Erpenbeck says, but then we rarely if ever see the whole.

Time after time she points to our limitations:

“Earlier I said the tension between one truth and another can’t be resolved. I’d like to expand on that now: One wonderful aspect of literature is that merely by naming this unresolvable tension, it casts a sort of spell, and while it may not give us the one, irrefutable truth, it does provide us with a structure that allows us to observe the many truths that exist parallel to one another. . . . Literature tells us that what we know is never the whole truth, but literature also tells us that the whole truth is waiting for us, if only we could read.” (104-5)

My title is a line from the book. If, Erpenbeck says, “according to scientific findings . . . the present belongs to us for precisely 3 seconds before it plunges down the throat of the past . . . [t]hat means that every 3 seconds, we produce ourselves again as strangers. What should I say, then, when I’m asked to say who I am? . . . [S]omeone whose childhood can now only be seen in a museum . . . ? [. . .] Or are the important things something else entirely?” [my emphasis]. (43)

What should be said in a piece of writing to convey what is important? What can be said? The political system of East Germany was. . . . The Berlin Wall fell during the presidency of. . . . The GDP of Germany now is. . . .

Or: “[A] lacquered wooden clock with golden numbers ticks throughout my entire childhood” on a street that dead-ends at an arbitrary political boundary, where men with guns wait. . . .

Time after time she points to our limitations . . .

“It’s really not so easy to find sentences that explain who you are,” Erpenbeck says. “Maybe it’s more important that beyond the borders of our own skin, beyond the borders of language, and beyond the various individual branches of the arts, we are engaged in a collective attempt to make something visible, audible, or perhaps indeed legible: the forgetting that lies behind us all, the unknown that contains us all, and the inconspicuous places where our own present takes shape.” (44)

Erpenbeck’s book is not really a memoir. It reminds me of the collected prefaces and essays of Henry James who discusses his own writing process, and, in its reason for being, of James Baldwin, who says:

“If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see. Insofar as that is true, in that effort, I become conscious of the things that I don’t see. And I will not see without you, and vice versa, you will not see without me. No one wants to see more than he sees. You have to be driven to see what you see. The only way you can get through it is to accept that two-way street which I call love. You can call it a poem, you can call it whatever you like. That’s how people grow up. An artist is here not to give you answers but to ask you questions.”

One of the many things that cannot be said easily is that very often good writing is “about” subjects that are powerful only to the degree that the writer discovers them to be powerful in herself, and which she can convey in a way the reader can translate. The something-more that literary nonfiction tries to get at is the experience of a life, the squaring our feelings with the data. In this, Erpenbeck says important things.