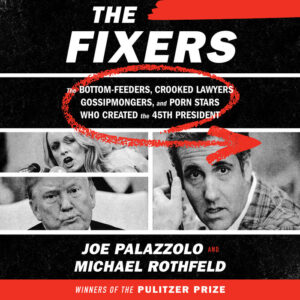

The Fixers: The Bottom-Feeders, Crooked Lawyers, Gossipmongers, and Porn Stars Who Created the 45th President

I’ve never met a successful man who wasn’t a neurotic. It’s not a terrible thing—it’s controlled neurosis. … Controlled neurosis means having a tremendous energy level, an abundance of discontent that often isn’t visible. It’s also not oversleeping. I don’t sleep more than four hours a night. I have friends who need twelve hours a night and I tell them they’re at a major disadvantage in terms of playing the game.

—Donald Trump, Playboy, 1990 ¹

Sooner or later, everybody who works for Donald Trump will see a side of him that makes you wonder why you took a job with him in the first place.

—Corey R. Lewandowski and David N. Bossie, Let Trump Be Trump ²

Real estate magnate and now President of the United States Donald J. Trump has played the game for a long time, or perhaps played a game. Whatever might be said about his lack of fatigue, he has surely exhausted portions of his audience. Such noted supporters and sympathizers as conservative pundit and verbal bomb thrower Ann Coulter, commentator Matt Drudge, creator of the popular news aggregate the Drudge Report, and television political commentator Joe Scarborough have wandered off the Trump reservation, awaking to the fact not simply that Trump is a con man—they knew that along, probably, but thought, as all people who overvalue intellect, that they were too smart to be truly fooled by a fool—but that he is seriously and corrosively neurotic. (Coulter recently filled the air with invective, venting her anger about Trump’s attacks against his former Attorney General Jeff Sessions—calling Trump “a moron,” “a retard,” “lazy,” “an idiot,” which, as it turns out, was only an imitation of Trumpian art of the putdown by insult, and imitation, as they say, is the sincerest form of flattery. Trump has the uncanny ability, inadvertently and implicitly, sometimes to turn even his most bitter critiques into perverse tributes.) But while Trump’s act has worn thin with some, he still retains some heft. He is mightily resilient because he is so cunning and because his uncouth style of politics so endears him to his considerable number of supporters. Some may be utterly tired out by his demented one-trick-pony act but for others he is a drug of which they cannot get enough, the repetition of the effect being the bliss of assurance. Trump knows his value to his supporters and his enemies: what would they do without him? What would they talk about? What would they love, what would they hate, without him? He provides the service of bringing everything into focus for people so sharply as to make them feel actually and honestly alive. He shapes reality for his friends and foes. That is no small skill and few politicians have done this as well as Trump has. As he once said, he likes putting “blood in the water,” even his own, constant crisis brings the adrenaline rush of emergency which is a good way to concentrate the clarity of hatred and admiration. He thinks, with some justification, that everyone should be grateful to him for this.

Trump plays the game by “playing” people. The sort of neurotic he is makes him highly skilled at this. But he plays people because he is enormously afraid of being played himself. Get other people before they get you, a morality he learned from his father Fred, who constantly told his son, as Harry Hurt III mentions often in his Trump biography, “You are a killer. You are a king.” The “killer king” is what Hurt called him and that fits well. All killers think themselves kings because they do something other people wish they could but lack the stomach for. And all kings must be killers if they are to rule absolutely. There is something psychopathic in all of this but psychopaths often make good leaders.

Trump also believes in luck and he has more of it than most human beings have a right to. For him, to be lucky is to be good.

Crime, show business, and politics have always been seamlessly connected in America and Trump was a more profound connector, more profound insider in each realm, than anyone else who had ever run seriously for the presidency.

The Fixers, written by a pair of investigative reporters from The Wall Street Journal and the other from The New York Times, is not a biography of Trump, but rather an account of the some of the sleaze and disreputable people he attracts. The underbelly of politics is not pretty for any major political candidate (and sometimes even for minor ones). The wheeling, the dealing, the corruption, the hangers-on, the backstabbing, the opportunists, the hustlers and hucksters, the influence seekers and influence peddlers, the true personalities of the candidates away from their lofty speeches and rehearsed-answer interviews, the entire atmosphere surrounding the world of politics and elections can be a bit breathtaking and a bit demoralizing. Trump’s career brings together Hollywood (before the reality show, The Apprentice, Trump had a considerable engagement with show business), organized crime (there was, for instance, no other way to get concrete to build structures in New York City except through the mob), and politics (Trump had a long-standing involvement with politics, once again, to become a player in New York real estate). Crime, show business, and politics have always been seamlessly connected in America and Trump was a more profound connector, more profound insider in each realm, than anyone else who had ever run seriously for the presidency. Trump’s celebrity, which obsessed him and his audience, was more synthetic, and, in this way, more remarkably broad, unique, really, than any other business person, pop culture figure, or wise guy operator.

The Fixers is a look into aspects of the underbelly world of Donald Trump, how it threatened to capsize Trump both as a presidential candidate and as president, and Trump’s reliance on particular two men to serve as his fixers for a time: his personal attorney Michael Cohen and tabloid publisher David Pecker. The book is about Trump’s relationship with Cohen and Pecker in the lead-up to his campaign, the campaign itself, the aftermath with Trump’s surprise election victory including the Mueller investigation and the launch of the impeachment.

As the book makes clear, Trump measured all his fixers against “Roy Cohn, the disgraced counsel to Senator Joe McCarthy turned lawyer to the powerful, [who] shepherded the young Trump along in his rise in New York City four decades earlier.” (xi) For Trump, no one ever matched Cohn who influenced him more than anyone aside from Fred, his father. As Palazzolo and Rothfeld write, “The Roy Cohn playbook demanded a relentless show of strength. The tactics he deployed in a fight appealed to Trump, who had internalized some of them before he met Cohn: Attack—mercilessly. Never admit you’re wrong. Declare complete victory, even when making concessions. Follow through only when pressed, and only as much as required.” (5) The foul-mouthed, blustering, aggressive, often woefully underprepared Cohn (he often felt he only needed to know who the judge was to represent a client successfully) represented Trump from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s. Trump brings up Cohn as the prime fixer even to this day. These characteristics of Cohn are Trump’s (understanding, of course, that showing strength is not the same as showing courage). Trump loves intimidation. For some people, fear has always been the best weapon to use to get what you want. This explains why Trump hates lawyers who settle. He wants to fight. Before he became president, he was involved in more lawsuits than all other presidents in our history combined.

As the book makes clear, Trump measured all his fixers against “Roy Cohn, the disgraced counsel to Senator Joe McCarthy turned lawyer to the powerful, [who] shepherded the young Trump along in his rise in New York City four decades earlier.”

Michael Cohen was a successful personal injury lawyer who owned a number of New York City taxicab medallions, and who, in 2001, bought units at Trump World Tower, which at the time turned out to be a smart investment. In a battle with the tenants a few years later, Cohen sided with Trump and won a seat on the condo’s board. Trump noticed how helpful Cohen had been in crushing the tenant uprising at Trump World Tower and thus Cohen entered TrumpWorld. By 2007, Cohen had morphed into Trump’s lawyer (one of them, at any rate), working with Trump’s financially stricken Atlantic City casinos, a business that Trump knew little about it. Cohen had some of Cohn’s characteristics or tried to fake them, tried to be the fighting, profane, hardass, pitbull for Trump, expressing a love and admiration for his boss that went largely unrequited. Among the jobs he was given was to tell vendors and lawyers who did work for Trump that they could expect reduced fees or none at all. (79) (There are many examples in Trump biographies of how he stiffed people and how cheap he can be.) And Trump went to Cohen to fix problems, to make something go away, like women with whom he had affairs. Cohen took care of this, perhaps not as well as he could have, in his zeal to protect the Boss. But slowly, then rapidly, Cohen begins to lose his usefulness. When Trump ignores Cohen after winning the presidency and does not bring him to Washington in any capacity, there is something nearly pathetic about Cohen’s blindly hopeful obsequiousness, rather like Jeff Sessions’s until recently when Sessions fought back. Trump can bring out that sort of devotion in some of his circle that seems cringe-worthy.

David Pecker published the gossip/scandal sheet, The National Enquirer among other periodicals. He too was captured, for some reason, by Trump’s aura, by the larger-than-life personality, by the grandeur of Trump’s own self-constructed mythology. The National Enquirer was important to Trump because it was a publication of significance to a major portion of the constituency he appealed to and that he needed. The journalism of the common folk. (So was Trump’s diet of “McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, pizza, and Diet Coke.”³ The food of the common folk.)

The Fixers tells us, in great detail and with an amazing cast of characters from lawyers like Michael Avenatti and Keith Davidson to former porn actress turned agent Gina Rodriguez and Trump World Tower doorman Dino Sajudin, how both Cohen and Pecker helped Trump, the former by paying off porn star Stormy Daniels to not reveal her one-night stand with a married Trump and lying to Congress about Trump’s interactions with Russian developer Andrey Rozov during the 2016 campaign in an effort to build a Trump Tower Moscow. Pecker paid Karen McDougal, a Trump mistress, so that she could not sell her story somewhere else to prevent it from being published, called “Catch-and-Kill.” Pecker’s, whose National Enquirer rabidly supported Trump, killed other potentially damaging stories. Both men wind up being dragged down by their association with Trump: Cohen goes to prison for income tax evasion and violation of federal campaign laws (the payment to Daniels, who violated her non-disclosure agreement despite hush money) and Pecker is exposed publicly as someone who killed stories to help Trump, badly damaging his already struggling National Enquirer which, as it turned out, was not even honest about the scandal it was peddling. Trump, an enormous liar himself, wound up enmeshing Pecker and Cohen in their own webs of dishonesty, not as innocents by any means but as operatives, because being dishonest was the only way they could really help Trump. And Trump managed to survive all of this. Like the Buchanans in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Trump never really pays the cost for the messes he creates. He is truly the killer king. In this respect, his fixers do what they are supposed to do—whatever the price may be for themselves: they absorb his troubles for him. As Palazzolo and Rothfeld write, “The men who had pledged loyalty to Donald Trump and made good on their promises to him met ignominious fates. Like Roy Cohn before them, Michael Cohen and David Pecker had been attracted to Trump’s aura and his gloss, to the force of the huge personality that had, finally, enabled him to be elected president of the United States.” (351) Later, they continue: “In his life as a business mogul, Trump had been able to find people who, attracted to his boundless ego, were willing to cater to his whims. Like the Wizard of Oz—or, as Cohen had suggested in Congress, a Mafia don—he’d make his orders known directly or in code to the fixers who carried them out, without leaving his fingerprints.” (365)

Like the Buchanans in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Trump never really pays the cost for the messes he creates. He is truly the killer king. In this respect, his fixers do what they are supposed to do—whatever the price may be for themselves: They absorb his troubles for him.

The Fixers is a solid piece of investigative journalism, an anti-Trump book, to be sure, but objective and fair enough to be read by Trump partisans with interest, and even a limited level of enjoyment. It must be admitted that Trump has done a great deal for the publishing industry: books about him, pro and con, sell well, and continue to flood the market. More books have been written about him during his first three years of the presidency than have been written about Barack Obama’s eight years. People are more fascinated by sinners than by saints, as it is said. Obama was frequently called the Black Jesus by his inner circle. More fittingly, Trump might be called Lucifer among the names that can be mentioned in polite company. He often referred to as the Orange Man but this hardly does someone of his magnitude justice. He is the Incendiary Blonde.