An obsessive researcher and consummate storyteller, Paul Hendrickson spins a world so detailed and complete, you can step inside, tiptoe into darkened rooms, eavesdrop on the chatter, live the life vicariously. His previous biographies (of Marion Post Wolcott, Robert McNamara, and Ernest Hemingway) were richly furnished with that authorial imagination. But his lyricism never came at the expense of the facts, let alone the truth—insofar as we can ever know it—of his subjects’ lives.

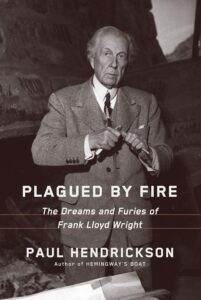

In Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright, Hendrickson raised the bar: He set out to find the hidden humanity of a man we now despise as a person, even as we laud his vision. Frank Lloyd Wright was the quintessentially American architect, freeing buildings from fussy constraints, making the interior spaces flow, using honest materials. He was also, as one early reviewer said in so many words, a jerk: He played fast and loose with the truth, with other people’s money, with other people’s hearts.

That review seemed to be rebuking Hendrickson for even daring to look for Wright’s humanity. Weary of the mandate to look only for clay feet and, the minute we spot a few toes, smash them, I raced to get a copy of the book. Then I settled in to enjoy Hendrickson’s noble quest and gorgeous prose—atmospheric and ornate, more Gothic Revival than Prairie.

What troubled me was not Hendrickson’s quest, but the conclusions he drew along the way.

He tells us up front what he is searching for: Wright’s “humanity, which, as a matter of fact, I contend was large—no, greater than large, in fact, immense.” Hendrickson warns that he will have to kick away “a lot of refuse, dross” before he unearths that immense humanity. True to his word, he exposes Wright’s fabrications and flaws, admits that Wright was an “overpowering and self-absorbed and neglectful father,” and notes that in his Dracula cape, billowy white shirt and pants pegged at the ankle, he was “as vain about his dress as he was about everything else.” This is not hagiography.

But the evidence he presents cannot bear the weight of his emphasis.

Hendrickson infers, for example, a homoerotic friendship with Cecil Corwin, a refined and possibly gay or bisexual architect who brought Wright into the firm as a young man, admired his genius, and admitted it superior to his own. “Let me see your drawings,” Corwin said when they first met and young Wright was looking for a job. To Hendrickson, this “almost sounds like a line from Mae West.” Really? When an architect draws for a living and this one is looking for a job?

True to his word, he [Hendrickson] exposes Wright’s fabrications and flaws, admits that Wright was an “overpowering and self-absorbed and neglectful father,” and notes that in his Dracula cape, billowy white shirt and pants pegged at the ankle, he was “as vain about his dress as he was about everything else.” This is not hagiography.

In Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography, the architect recalls that he asked Corwin for an advance of ten dollars to send to his mother, and Corwin “said nothing, took a ten-dollar bill from his pocket and laid it on the table.” To me, that sounds like a man who was either trying to preserve the kid’s pride or hoping this was not the first of many requests for advances. To Hendrickson, “there’s an odd ring to this sentence. Almost as if some kind of sexual transaction has been made.”

Hendrickson goes on, noting that in the autobiography, Wright does not distance himself from his admiring friend or mock his sexuality, and in a nostalgic letter years later, writes to Corwin, “We were Damon and Pythias.” Hendrickson pounces on the phrase, which can be construed to represent a homosexual bond. But it can also be taken in its original meaning, the Pythagorean ideal of loyal male friendship, which is how it was used to describe Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, how it was used in The Philadelphia Story, how it was used for a pair of famous World War II fighter pilots …

Why take such trouble with a theory that matters so little? Even Hendrickson calls the relationship “unconsummated.” But he leans on his theory as an early proof of humanity, labeling Wright’s brief, kind mention in the autobiography as a “protective tenderness toward Cecil.” (Why would Wright, an egoist by all measures, distance himself from someone who understood and wholly appreciated his talent?) Then Hendrickson muddies his own suggestion of “protective tenderness” by suggesting, with no stronger evidence, that Wright’s own sexuality was…complicated.

He takes similar liberties psychoanalyzing the Wright photo album. Family photographs can be sharply revealing—but he reads into these photos what he has learned in other ways, presenting them as foreshadowing events years in the future. “Is it only a circumstance that Kitty leans ever so slightly to the left, away from her husband?” he writes, ignoring the fact that Kitty is leaning against her sister-in-law, probably for support, because they are sitting on stone steps and Kitty is balancing her new baby on her lap.

That photo, incidentally, was taken nineteen years before Wright abandoned his family. Yet Hendrickson also pounces on the fact that Frank Lloyd Wright is the only one in the photo not looking at the camera. (He is looking toward his wife and their new baby, which rather undercuts the point.)

In a 1901 article in Ladies Home Journal (eight years before Wright went off with his lover, Mamah) he says of his open floor plan that he is trying to present “the least resistance to a simple mode of living in keeping with a high ideal of the family life together.” Hendrickson wonders if he “somehow knew in his glands, he was writing a kind of epitaph for his own life story, and its coming crash.”

Oh, for God’s sake.

“The words ‘family life’ and ‘together’ although next to each other on the printed line, amounted to a beautiful lie,” Hendrickson writes. Did they? Or was Wright simply a man capable of idealizing something he could not make last? Could it be that, through his work, he encouraged others toward the sort of abiding domestic peace he would never succeed in attaining for himself?

The biography before this one, Hemingway’s Boat: Everything He Loved in Life, and Lost, was stunningly good. It is easy to see why Hendrickson would turn his attention to another self-centered, cocksure genius. But now, instead of the taciturn machismo of Hemingway, Hendrickson confronted the florid narcissism of Wright. Conjoined, the larger-than-life subject and the author’s own dramatic style take the book right over the top.

Plagued by Fire dangles all manner of interesting material along the way, debunking several of Wright’s whoppers and canards and providing tons of context and digression.

Structurally, Hendrickson chooses pivotal scenes from Wright’s life rather than attempting a straight chronology. This allows some lovely, impressionistic scene-setting and effective spotlighting of the turning points. But in an effort not to lose us as he moves back and forth, he uses almost too much wayfinding: “Pausing here.” “To remind you again.” “Again, why is this worth mentioning?” “Pausing again”…

Plagued by Fire dangles all manner of interesting material along the way, debunking several of Wright’s whoppers and canards and providing tons of context and digression. There are wonderful quotes—a former apprentice hands Hendrickson his title when he says, “Frank Lloyd Wright attracted fire.” There are intriguing cameos of several of Wright’s clients, marveling that their lives were almost as melodramatic as his. (They were rich, brave enough to defy norms, hungry for what was novel and daring. Such lives take on color.)

Throughout the book, Hendrickson painstakingly chronicles his own hunt, taking us with him even to destinations that yield little or nothing. Again and again, understandably, he returns to the central tragedy of Wright’s life: the day a crazed employee ran through Taliesin with a hatchet, slaughtering Wright’s lover, Mamah Borthwick; her two children; and four other people. We wait, sure that this brutal and inexplicable massacre will transform and soften Wright, revealing in some unmistakable way the humanity we are all, by now, seeking.

But Hendrickson seems to find it sufficient that in the weeks after the massacre, Wright was depressed and sleepless and suffered fever, chills, and boils, and that one day, he stood so close to a rushing creek that an onlooker grew worried and yanked him back to higher ground. Of course he was traumatized, rendered vulnerable in a way he had previously escaped. What happened at Taliesin was earth-shattering. But we cannot even know which aspects of the tragedy haunted him. The random senselessness? The loss of his great love and the brutal killing of her children? His own failure to be there and stop it? The destruction of Taliesin itself, his masterwork?

Wright went on to do his best work, and Hendrickson interprets his turn toward more affordable housing, rather than the showplaces that first made his name, as a reformation. But the ideals reflected in that later work were consonant with the philosophy he had expressed all along, and it could also be true that fame accorded him the freedom to do what he had always intended.

For literary purposes, Hendrickson uses Taliesin as a synecdoche, noting that the setting and tragedy contain all the passion, beauty, arrogance, and fire of Wright’s life. But then he goes further, interpreting an obviously psychotic killer’s act as a sort of biblical wrath visited upon Wright because he had left his wife and children to be with his lover. Hendrickson even sets up a weird supposed parallel with Wright’s cousin, Richard Lloyd Jones, a racist newspaper publisher whose vicious rhetoric may well have laid the foundation for the 1921 Tulsa race riot.

Again and again, understandably, he returns to the central tragedy of Wright’s life: the day a crazed employee ran through Taliesin with a hatchet, slaughtering Wright’s lover, Mamah Borthwick; her two children; and four other people.

“And why am I thinking in such unprovable directions at all?” Hendrickson asks. “Because, as I’ve also tried to say in one form or another throughout this narrative, I believe Frank Lloyd Wright himself came to think in these directions—or at least to wonder about them.” This is, Hendrickson adds, something “you have to search for in the margins.”

Earlier in the book, he described his subject living “a life largely of seeming Old Testament disaster and disarray, plenty of it his own making.” But plenty of people abandon spouse and kids for a lover without having their house set on fire and seven people slaughtered in retribution. When Mamah Borthwick’s dear friend dies suddenly a few months after Borthwick and Wright had run away together, Hendrickson writes, “It was almost as if her sudden dying was some sort of proxy sorrow for someone else’s moral selfishness.” Again, if a friend died every time a woman ran away with someone else’s husband…

Even the tiniest speculations grow annoying. A woman sends Wright a sympathy note, and in her penmanship, Hendrickson tells us, “the word ‘immensity’ could almost be ‘university.’ Maybe it is. It would fit with her looniness. The university of your sorrow.” We are now on a journey through Paul Hendrickson’s brain, not Frank Lloyd Wright’s.

By the end of Plagued by Fire, I found myself wishing that Hendrickson had written a novel, based on Wright’s life, and let the momentum of the story carry us. I suspect more truth would have landed, had he not been forced to interrupt his narrative every other paragraph to stipulate what was known and what was uncertain about Wright’s life, where he was just guessing, and which previous authors had been “unwittingly reliant on his lies.” Hendrickson sinks us into Wright’s version, giving the sensory details that make it vivid, then pulls back and coolly deconstructs the scene, often admitting that there is little evidence to support it. This is a neat trick, sliding back and forth between the roles of poet and critic, but the seesaw continues until we are dizzy.

The scrupulous care he takes to annotate as he goes, in the body of the text, makes for an odd contrast with the liberties he takes in drawing his own conclusions. He will guess freely at love, hate, sexuality, and motive, yet doubt previous records with little justification. After Wright left his wife, the fact that the Chicago Tribune quoted Kitty Wright at length was cause enough for Hendrickson to write, “Had she actually said about a fourth of what they’d attributed to her?” She was a bright woman. It is not inconceivable.

By the end of Plagued by Fire, I found myself wishing that Hendrickson had written a novel, based on Wright’s life, and let the momentum of the story carry us. I suspect more truth would have landed, had he not been forced to interrupt his narrative every other paragraph to stipulate what was known and what was uncertain about Wright’s life, where he was just guessing, and which previous authors had been “unwittingly reliant on his lies.”

He also second-guesses a Tribune quote from the killer’s widow: “We were well treated and liked the place, but my husband had the notion that he was being pursued. He recently got to waking me up in the night in our quarters in the bungalow to listen for noises.” Hendrickson says “those quotes sound half-invented.” Really? A staff writer for The Washington Post for decades, he could certainly suspect someone of “cleaning up” grammar or word choice. But “half-invented” is strong, when what she is saying about her husband’s paranoia is so plausible. She continues: “‘They’re trying to get me,’ he kept saying. Then sometimes he would choke me and threaten to knock my brains out. He took that hatchet to bed with him.’” The Tribune also quotes others describing the killer’s extreme excitability and moodiness. “In a way,” Hendrickson writes, “It’s almost as if the newspaper is describing a character named Bigger Thomas in a yet-unwritten fiction called Native Son.”

After setting up the motive for the massacre as the book’s second question, Hendrickson finally concludes, “He did it because he was mad. Gone berserk. All the rest is anybody’s argument, and has been for a century.” That said, he proceeds to resurrect a few tattered conspiracy theories, mainly to dismiss them and write, “In place of any real knowing, it’s time to pivot.” There is far less mystery here than his swivels and ponderings suggest. A single ego slight can trigger a rampage in someone whose mental instability leans toward violence; we have seen this again and again. It is a painful truth, not an elaborate puzzle.

And so we return to the central quest: the immense humanity. “My contention,” he writes, “is that traces are always there, visible and yet not visible, hiding in plain sight, going away fast, coming back when you least expect it, sheared off as if from a brick face, and all because of so much damnable ego and arrogance.” So many words, all to say we have not found it yet.

Nor have we given up. Hendrickson finds a single page at the end of Wright’s autobiography: four memories, each beginning, “I remember.” The memories are of his children, Hendrickson says, adding that there is no way anyone could despise his ego on that page because each memory is “so artfully rendered. With so much seeming honesty, vulnerability, plainspokenness.” I read on eagerly. But the first memory Hendrickson cites is Wright listening to music and being overtaken by an anguished despair—without saying why. Hendrickson tells us he has just received a letter from his daughter, but in the quoted passage, Wright dwells only on his own misery.

“I for one do not subscribe to the proposition that Wright was always too much of a narcissist to be able to give himself over wholly to another human being,” Hendrickson writes. “I think it’s a far deeper story than that.” No doubt it is—but it will remain untold. We cannot trust a single page of Wright’s autobiography, Hendrickson tells us (except maybe that one about the memories?), his son’s recollections do not help, and all of Wright’s correspondence with Borthwick is gone.

America’s favorite architect tried to tug the entire country toward nature, toward democracy, toward honesty. A frank egoist, he stayed large-minded, nothing mediocre or niggling about him. Whether the casualties he left in his wake caused him pain, we will never know.

In the end, Hendrickson’s quest does succeed—just not in the way he leads us to expect. Throughout the book, he refers to “the back of” Wright’s life, as though it is an edifice. But it is the edifices Wright designed that reveal his humanity. We hear it when he articulates his vision; we hear it in Hendrickson’s descriptions of the structures. Sitting in Unity Temple helped Hendrickson “find, or re-find, the person who I think Frank Lloyd Wright really was.” A visitor feels weightless there. The acoustics are magical. No seat is more than 45 feet from the pulpit. The space is the point.

“He wanted to let light and space in, air in, life in,” Hendrickson writes. America’s favorite architect tried to tug the entire country toward nature, toward democracy, toward honesty. A frank egoist, he stayed large-minded, nothing mediocre or niggling about him. Whether the casualties he left in his wake caused him pain, we will never know. But what shaped his particular genius is a question far more interesting than whether his life’s central tragedy was retribution, even in his own mind.

In the last decade of his life, Hendrickson notes, Frank Lloyd Wright produced nearly one-third of all his designs. That work expressed him in the only way he felt comfortable being vulnerable, because he stood on a platform that raised him above everyone else. In the end, he gave what was best in him to his work, not to those he loved—or his biographers.