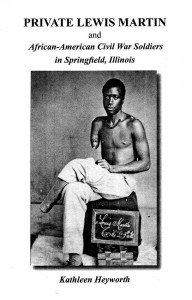

This slim but informative volume, sold at the gift shop of the Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, has the charm and modesty of being the work of an amateur historian. It is not written as much as it is earnestly reported. This work is also accidental; the author was doing research on Camp Butler that, as though pulling a thread, led to an interest in 29th United States Colored Troops (USCT) who were at Camp Butler in November 1865, after they had been mustered out in Brownsville, Texas, to get their final pay. The interest in the 29th USCT led to uncovering information about the African American John Bross Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Union veterans’ association Post of Springfield. One of the signatures on the charter for the John Bross Post was Lewis Martin, which the author immediately tied to the “Louis” Martin of the famous daguerreotype that featured a young black man who is a double-amputee, missing a portion of his left leg and most of his right arm. In this way, Kathleen Heyworth found her subject through the design of happenstance.

Beyond the photo, there is little known about Private Lewis Martin, but Heyworth seems to have found what little there is, and that little is actually of some importance. “Lewis Martin was born a slave in Independence County, Arkansas around 1840,” so Heyworth begins the tale. Apparently, he, his mother, and two brothers were the property of William and Nancy Martin. Nothing is known of Lewis Martin’s childhood or family life, nothing known about what type of work he did as a slave. Heyworth estimates that Martin escaped slavery in 1862, during the tumult and chaos of the Civil War, as did thousands of other black folk in bondage. Martin and his family were living in Upper Alton, Illinois at the time when the Illinois 29th USCT was formed in 1863. In 1864, Martin, according to his military records, was 24 years old, six feet two inches, and worked as a “farmer.” He was also listed as free prior to April 1861. As Heyworth explains, “Many escaped slaves still feared that they could be returned to slavery if they admitted that they had been slaves. Also, there was an inequality between the pay the colored troops received and the pay their white comrades received. When Congress enacted legislation in 1864 that gave equal pay to colored soldiers (retroactively to January 1), there was another stipulation: only colored soldiers who were free prior to April 19, 1861, received back pay and a bounty.”

Martin left no word about what motivated him, but it is hardly likely that he was very different from the other black men who fought in the Civil War, and they nearly all fought for these reasons: honor, self-respect, and as a self-defining, self-determining political action. Let us say they fought for the right to their own hearts and minds.

Surely, Martin joined the army in part because he wanted to strike a blow, personally and forthrightly, against slavery. Intimately connected to this assertion of political opposition, nay, resistance to the forces that oppressed him and his race was a need to assert his manhood, to express his masculinity by fighting and proving himself worthy of his freedom—proving that he had in fact earned his freedom, rather than having had passively accepted it through a presidential edict. For him and the nearly 200,000 other black men who fought for the Union, military service was both a personal fight against slavery and also a cry for full citizenship, as military service often is for the socially alienated, the economically dispossessed, and the politically disempowered. (Blacks would continue to use military service as a lever for full citizenship and the permanent disabling of institutional racism for the next 100 years following the Civil War.) All of this is speculation of a sort, since Martin left no word about what motivated him but it is hardly likely that he was very different from the other black men who fought in the Civil War, and they nearly all fought for these reasons: honor, self-respect, and as a self-defining, self-determining political action. Let us say they fought for the right to their own hearts and minds.

Martin received his terrible wounds at the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864. Heyworth provides a good account of this bloody loss for Union forces, reminding readers of how awful combat encounters between black Union and Confederate soldiers were: the Rebs, insulted that members of a “servile race” were taking up arms against them and determined to exterminate them with no quarter given; the blacks, knowing that the Rebs intensely hated them, would fight with their own special ferocity as, probably, a combination of revenge and their best chance of surviving the conflict. (Recall, as examples, how bloody interracial Civil War combat was in the horrific Second Battle of Fort Wagner, memorialized in the 1989 film, Glory, and with the massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow, mercilessly attacked by the famous, or infamous, Confederate General and slave trader Nathan Bedford Forrest.) Heyworth graphically and usefully describes the extent of Martin’s wounds, the type of ammunition that caused them, and the medical treatment he received at L’Ouverture Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, and Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C. The fact that Martin survived double amputation at the time without succumbing to shock, infection, other diseases like dysentery, and the like, is miraculous. One has only to read slavery escape artist Harriet Tubman’s account of being a nurse at a black hospital during the Civil War—where, during the summer, it was unbearably hot, smelly, with sick patients moaning and covered with flies—to know the ordeal that Martin endured.

Martin lived the rest of his life in Springfield, Illinois, where his wounds made it impossible for him to do any physical labor. He could not read and write, so any other type of sedentary work was unavailable to him. There were days when he was so incapacitated that he could not dress himself. He lived on a $24 monthly Army pension until, through legal action, it was increased to $72 monthly in 1889, “one of the largest civil war pensions ever made to a Springfield Civil War veteran,” according to Heyworth. Apparently Martin’s post-Civil War life was unhappy. He was an alcoholic, probably self-medicating chronic pain and the psychic shocks of having endured combat and military medical treatment. He died on January 26, 1892, of either a stroke or alcohol poisoning at the age of 52 or thereabouts. He left his money (he received more than $6,000 in back pay as a result of his successful suit) to Maria Brill, a white woman with whom he lived, who may have been a caretaker, a lover, or some combination of the two. He was buried in an unmarked grave, a situation that was not rectified until 2012 when Heyworth joined others in a successful campaign to raise money for a marker and headstone which were unveiled on November 2, 2013.

Now, what all of this has to do with Presidents’ Day seems obvious. Martin lived most of his adult life in Abraham Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield. But that is superficial. Had it not been for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, announced in 1862 and officially enacted on January 1, 1863, Martin would never have had the chance to fight in the Union Army as Lincoln’s order (which many blacks at the time complained did not actually free any slaves) did permit them to fight for the Union Army. The act, in essence, elevated black men from being “contraband,” as escaped slaves were called, to be soldiers, to being recognized as actionable human beings by the republic. Granted, that Lincoln had to be talked into the idea of having black men fight for the Union by Frederick Douglass, the point is he was sufficiently amenable or reasonable to be talked into it. The Emancipation Proclamation changed the nature of the war, as it made slavery the thing that doth officially prick the cause of the conflict; made it possible for black men, as Lewis Martin did, to pay the price for their freedom in blood, a price that would forever end any pretense of a peaceable racial order of subordination on the southern front in the never-ending war for equality. All of this is inerasably and symbolically captured in a photo of a black soldier’s mutilated body.