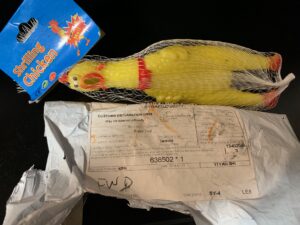

Carl ships and receives many packages each month, some internationally, for his online business. The plastic chicken he got in the mail from Cambodia last week was not expected.

Someone must have sent him the Shrilling Chicken as a joke, he thought, since it looks like a sex doll and the customs form declared it “repair tools.” There was no return address. But his friends insisted they did not order it for him.

After looking into it, Carl has decided he is a victim—“object” might be more accurate—of a scam called “brushing.” Brushing is a term that began to be used in 2017. The idea is this:

You own a company in China that sells cheap Bluetooth speakers. You would like for Amazon (or Alibaba, the Chinese company that outsells all U.S. online retailers combined) to put your speakers in front of shoppers, instead of burying them on page 18 of results. So you pay fake shoppers to surf Amazon, pretending to look for speakers. After a time, they buy yours. Amazon’s algorithms note their activity.

Because you fulfill your own orders, instead of having them picked at Amazon warehouses, you ship something to a random person in the United States: Carl. But Carl, after all, is expecting nothing, so why ship him speakers worth $25 in materials and labor?

Any plastic chicken will do, since it weighs mere ounces, and shipping is super-cheap. (A one-pound package sent from Beijing to New York City has been only $3.66 recently, thanks to U.S., not Chinese, mail subsidies. That is soon to change, now that the Trump administration has withdrawn from the Universal Postal Union.)

There is no return address on the envelope or invoice in the package, so it cannot be returned, and who cares if it ends up in an American landfill? Soon the Americans will agree to anything to outsource their waste—another profit center.

In the meantime, your fake shoppers leave glowing reviews at Amazon—maybe even posing as Carl—about their new Bluetooth speakers. You reimburse them for their purchase and pay a pittance for their time.

Brushing is a form of marketing that costs very little, compared to ads and other promotion, which might never take effect in a glutted market, especially against multinational giants with name-brand products.

Carl, who says there will always be cheaters in the capitalist system, because that is the game, did a little math for me. The plastic chicken (hair bands seem to be popular too), shipping, and fake shopper cost probably three bucks. Ten chickens a week, $3 per, that is 120 a month. From that comes glowing reviews, the algorithms’ attention, and maybe a first-page Amazon position, which could return tens of thousands in sales. Gaming the Amazon system? Priceless, or at least affordable. Carl is admiring.

Who are the victims of brushing? Some Americans profiled in news reports about it worry that their names and addresses are known, but that information is out there. Some gripe about the time they spend on the phone arguing with Amazon or the post office over hair bands. Others worry they might receive drugs or guns, not chickens or hair bands, but those are expensive. The kind of people who worry for the rich say Amazon’s profits might be affected, somehow, perhaps by diminishing confidence in their platform. (On the consumer side, a site called Fake Spot helps identify fake reviews.)

Carl thinks the only crime here is waste, which he says all systems encourage. Forty chickens a month, times 10,000 companies worldwide trying to game the system, well, that is a lot of chickens. But he got his.