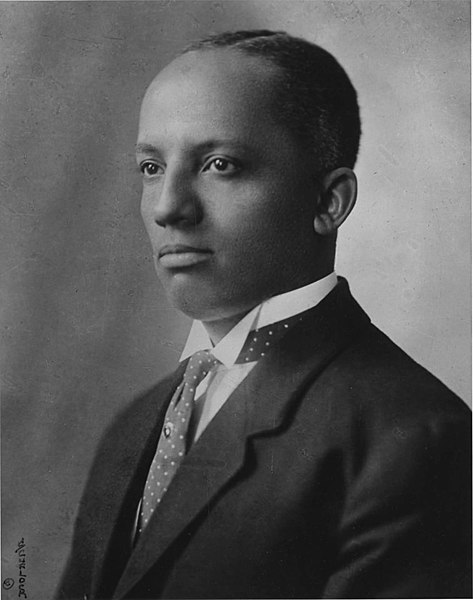

Dr. Carter G. Woodson in a 1915 photograph.

1. The Obsessed Raider of the Lost Black Ark

When I was a schoolboy, Black History Month was known as Negro History Week. It was celebrated during the week of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12. (I especially liked the month of February as a child because there were two national holidays: Lincoln’s birthday and George Washington’s birthday, February 22. If we were hit with a snowstorm or two, February could feel almost like a vacation from school.) The week of Lincoln’s birthday was also when Frederick Douglass’s birthday was celebrated (February 14), or when Douglass chose to celebrate it, as he did not know the exact date of his birth. These birthdays, as the story goes, is why historian Carter G. Woodson chose this week in February for Negro History Week, which he started in 1926, during the height of the New Negro Movement, with some degree of fanfare and with the sort of organizational grit and administrative determination for which he was known.

Woodson, born in 1875 in Virginia, is the only Black American both of whose parents were slaves to earn a Ph.D. He earned his doctorate in history at Harvard University. His dissertation advisor was Albert Bushnell Hart, who was W. E. B. Du Bois’s advisor. Du Bois was the first Black to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. Woodson was the second. It was not an easy task as Bushnell and Edward Channing, the other Harvard historian with whom Woodson worked, did not think that the Negro had a history. They challenged Woodson to prove them wrong. Woodson did not exactly do that with his dissertation, which was on the secession of West Virginia during the Civil War. But Woodson would dedicate his life to just that task, the unearthing of Negro history, so it might be said that his education at Harvard did him a favor. Or his “miseducation” as Woodson characterized it. Woodson claimed that it “took him twenty years to recover from the education he received at Harvard.”¹ Speaking of miseducation, Woodson’s most popular and accessible book, among the many he wrote, is The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), a powerful polemic that is still widely read by Blacks and remains highly influential. Critical Race Theory, whatever the merits of its claims, might be better understood in the context that Blacks have long believed that they have been the victims of a purposeful miseducation that they feel needs to be corrected. The Mis-Education of the Negro is one of the most scathing, most devastating critiques of the United States I have ever read by a Black person who was not a communist, explicitly saying so. Woodson lived and died a Race Man, through and through, and however much some of his ideas coincided with Marxism, they owed little or nothing to it.

Some years ago, I attended a talk by Lorenzo Greene, retired from Lincoln University, a noted Black historian who worked for Woodson for many years. Greene told war stories about working for this unrelenting taskmaster, whose sole aim in life was creating and propagating Black history. Woodson’s biographer writes about his time at Harvard, “It was remarkable that Woodson completed his dissertation, revised it for publication, and researched, wrote, and published a monograph on black education all while holding down a full-time teaching job.” Woodson never stopped working at this rate for his entire life. As Greene told it, Woodson had the zeal of a missionary, the work ethic of a union organizer, and the determination of a guerilla filmmaker. He pushed those around him as hard as he pushed himself. He died in 1950. As hard as he worked, it is mildly surprising he lived as long as he did. Probably the work kept him alive. His biographer notes that many of Woodson’s contemporaries, such as Du Bois and historian Rayford Logan, thought the creation of Negro History Week was, among Woodson’s many achievements, his greatest.²

2. What Negro History Week Taught Me

Negro History Week was for me, in elementary school and junior high, when nearly all my teachers and the entire student body were African American, one of those “dutiful” occasions. I likened it to National Brotherhood Week, which was a big deal in Philadelphia schools because the word “Philadelphia” literally means “City of Brotherly Love,” as I was constantly reminded. Both of them, in their own ways, were about civic virtue: for National Brotherhood Week, it was being a caring, responsible citizen; for Negro History Week, it was being a caring, responsible Negro who knew about your race.

I do not think that I and my Black classmates were interested in knowing much about our race’s history. History is not a subject that interests most children, who do not see a need to know about things that happened before they were born. Most of us thought Negro history was a particular burden. Negro History Week typically focused on slavery, which we found a depressing, nay, distressing subject. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were mentioned as heroic slaves. (No one used the current term “enslaved persons” when I was a child, so we thought Black and slave were interchangeable terms.) We were told about the Underground Railroad, which most of us thought was some sort of subway system. We were told that Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves with something called the Emancipation Proclamation, (the two biggest words I knew how to spell in the third grade, along with Philadelphia and Pennsylvania). We were told Lincoln was a great man. (In the playground, the kids would chant: “Abraham Lincoln was the king of the Jews/He wiped his behind with the Daily News.” I have no idea why we said this or what it was supposed to mean but it made us all laugh like crazy. We were also convinced that Lincoln was a Jew; what other White person would be interested in freeing Blacks but a Jew?) In fifth and sixth grade, we read chapters from Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery (I once did a class report about the book), were told about George Washington Carver (I did a class report about him too), and learned something about singer Marian Anderson, because she was famous and from Philadelphia. We sang some Negro spirituals during Assembly and were told they were code songs. Something was said about Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the wife of a great president and who cared about Negroes. And that was Negro History Week as I remember it.

Most of us were glad when this little educational speed bump was crossed and we could get back to studying White people, which did not interest us greatly, but which seemed normal. After all, we were a minority group, as we were constantly reminded; Whites were the majority and, naturally, they did most of the important things in the country, the most important being running it, which we all knew they did. Besides, in my schools, we never talked about Black people at any other time during the school year so, naturally, we kids felt it to be an anomaly, not normal.

And we were all ashamed. After all, it was mostly about slavery and being downtrodden and mistreated. And despite the teachers telling us about fugitive slaves and abolitionism (I do not remember being told about slave revolts), what we “knew” about slavery was from Hollywood movies like Gone with the Wind, where Blacks were shown as subservient and eager to please their White masters. The only thing that was worse was seeing Blacks in jungle movies wearing loincloths and throwing spears, or a Black person in a Three Stooges short rolling his eyes in fear of ghosts and saying, “Feets don’t fail me now!” We laughed at it so we would not have to cringe or even think. Critics of Critical Race Theory instruction say that it would make Black children feel like victims. When I was a pupil, it would have been something of a promotion if I could have felt like a victim during Negro History Week. As a victim, I could have at least felt anger, hatred, determination, felt like a mistreated person deserving justice. Instead, I felt less than a victim, more like a non-entity, a cipher. I felt like a scarecrow being stuffed with what someone thought was the straw of life but never brought to life.

I do not blame this on my teachers, who were a dedicated lot, determined by racial duty to teach us as well as they could. I do not know what constraints they were under and besides, I am recounting what I learned, not necessarily what someone was trying to teach. I sensed in some respects they were as uncomfortable teaching us about slavery as we were learning it. Negro History Week made learning about Negro history seem unnatural, foreign, and alienated most of us from the subject. It simply made us feel self-conscious in a way that most of us struggled with ineptly and immaturely, poor, Black working-class pupils that we were.

I grew up in an Italian neighborhood called, appropriately enough, “Little Italy.” This happened because an Italian family chose to rent a small bungalow attached to their house to my mother. They did this because my mother was a widow with three children who worked as a school crossing guard for the neighborhood Catholic school, which admitted only children of Italian descent. The fact that my mother was a widow, not a single mother, and that my father fought during World War II and was buried in a military cemetery made us “exceptions.” The Italians, by and large, loved us, a sentiment they did not generally feel for Blacks. There was always a sort of tension with my Black friends who wondered, often aloud and rudely, why the Italian boys liked me so much or, worse, why I liked them. As I attended all-Black schools, an all-Black church, and spent most of my time with my Black friends, I was by no means deracinated or alienated from Blackness, such as it was at the time of my childhood. But I did spend more social time than nearly any other Black child in the neighborhood with the Italians.

One of my best friends for a few years during my childhood was an Italian boy, whom I will call Sonny, and his younger brother, whom I will call Joey. I was a bit older than Sonny and so both of them were like younger brothers for me. And as I had no brothers this made me feel special. For a time, we were inseparable, played together, went everywhere together. When my Black friends would chastise them, and not want them around, I would defend them and make my Black friends accept them. I even took them to my Black barbershop once when I got a haircut, probably the only time Italian boys ever set foot in the place. I wondered why they never took me to their barbershop when they got haircuts. This bothered me a little. I was about ten or eleven when the friendship ended abruptly. One day I was spinning tops with Sonny, who at this time was probably about nine, and Joey, who was seven. Joey was always fascinated by my color, which he swore came from drinking chocolate milk. He used to tell me that he was going to drink chocolate milk and become brown too. I always laughed at this, telling him he was going to have to drink a lot of chocolate milk to look like me. On this day, he told me he had been drinking chocolate milk lately and he was turning brown. He showed me a brown birthmark on his arm, which had always been there, as proof of this. I teased Joey about this, saying that was just a birthmark and he was not turning brown yet. He still had a long way to go to look like me. “You gotta start drinking a quart or two of chocolate milk a day if you want to be brown like me,” I grinned. Sonny, for some reason, became irritated about my teasing his brother about turning brown, and that his brother was still going on about wanting to be brown. He suddenly yelled at me, “That one brown spot looks better on him than it does all over you. Nobody wants to be brown like you.” I was deeply wounded that he said that. I thought we were friends and that my color did not matter to him, that it was all a game of who drinks white milk and who drinks chocolate milk. I did not think he would ever insult me. Is this how he really thought of me? We continued to play as I ignored what he said but it was not the same. My heart had gone out of it. We drifted apart after that.

Obviously, what Sonny said affected me, for I have remembered it my entire life. But I have remembered insults from my Black childhood friends as well. What is different is that I felt that Sonny’s remark was a betrayal. I had been duped. I had been a better friend to him and his brother than he had been to me. And he felt secretly that I ought to be the better friend because I was Black, that he had been doing me a favor by being my friend. And if he felt pressured by his Italian friends to distance himself from me, then it showed that he thought less of me than he did of them. My mother had taught me that life was a hard teacher and now I finally realized what she meant. This was a hard lesson. But I was not traumatized by it. I had learned enough from Negro History Week to know that there were Black people who had it a lot tougher and had learned harder lessons in a harder way. They soldiered on. I would not be much of a Black person if I let something like this really get me down. Long before I ever heard of Nietzsche, I grasped intuitively from Negro History Week something like, whatever fails to kill you makes you stronger. It made me almost appreciate Negro History Week for at least that moment when I thought about what Sonny said. And I thought about it a lot after it happened, although I never told my mother or my sisters. I worked it out for myself with the help of Negro History Week. I realized Sonny’s remark did me a favor by making me think about my race less naively and by making me feel more alive. All of this made me understand better something that Black comedian Bert Williams once said: It is no disgrace to be colored, but at times it is painfully inconvenient.

• • •

¹ Jacqueline Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993), 26.

² Ibid, 84.