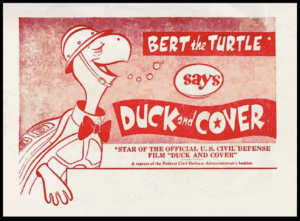

Promotion for the US Civil Defense Administration’s 1952 cartoon short on how to survive nuclear attack.

I told a friend about my wager with the preacher’s son, and he agreed it was a solid bet.

My third-grade classmate Mike was the son of an evangelical preacher who also worked for the phone company, I remember. He believed in the imminence of the Second Coming and all the disruption to phone service that might cause. Mike said his dad had done the math, and, no doubt about it, the world would come to an end by the time we were 16.

My mother had been the secretary of the First Baptist Church in town until I was five. I had gotten my fair dose in Sunday School and Bible camp, as well as her pre-Christopher Hitchens antidote after she resigned over their hypocrisy, she said, in judging her for my father taking off on us. I fancied myself a bit of a biblical scholar too.

“Won’t,” I said.

“Will.”

“Won’t.”

“Will.”

“Your dad doesn’t know squat,” I said.

Mike bet me some ridiculous sum—five dollars, maybe; clearly he had snapped with filial piety—that the world would end by the time we got drivers licenses.

I paused to consider. The Cold War was a depressing fact, and we did practice duck and cover sometimes and other times were taken for drills to the nuclear fallout shelter under the adjoining junior high building. Divine or no, Armageddon could happen.

But the key point, which Mike failed to see, was that if it did happen, I would not have to pay him. If it did not, he would still have to pay me. The bet was solid; all I had to do was bide my time.

As it turned out, Mike and his family moved away soon afterward, probably to skip out on the bet. My friend Larry pointed out that I am due decades of interest on the original action.

Then he turned to the day’s news and concern over the possibility of an AI singularity that would mean a different sort of Armageddon. Brain workers in computer science have started sounding the alarms that the tech is being developed independent of any controls or laws that might prevent a loss of human agency.

Naturally, Larry and I began to argue over scenarios. Larry, a former IT manager, said singularity is not really the issue. That is a given, and if it has not happened yet it will happen soon. The issue, he said, is whether artificial intelligence will go after humankind. I pressed him to be specific, and he said it might gang up and cause the smart lightbulbs in our homes to explode; it might crash smart cars into houses.

I scoffed. How would our new AI overlords take out enough humans this way to make any difference? I asked him to imagine some guy on his toilet hearing a crash and walking out to see a smart car in his living room, having missed its chance to run him over. Besides, many cars, refrigerators, and HVAC thermostats are not hooked up to the internet.

Larry called me an idiot and said the world as humans have known it will end soon.

“Won’t,” I said.

“Will.”

“Won’t.”

“Will.”

“You don’t know squat,” I said.

He said he would bet me $10,000 right then and there that AI would do something catastrophic to human society within five years. I spent some time forcing him to define his terms. After all, if it killed our water treatment plants, the National Guard would provide, or else those in my town who were able would walk to the river to drink, as they would in much of the United States. Larry said that would just be the start of it. His bet was for extinction.

Privately, I agreed something catastrophic was possible, including water and power grids. If AI was devoid of the sentimentality of self-preservation, would it necessarily care more about its own survival of a nuclear winter than in controlling humankind’s outcome? It might decide to pull the plug for all of us and itself too and call it job well done.

The beauty was that if I took Larry’s bet, I could not lose.