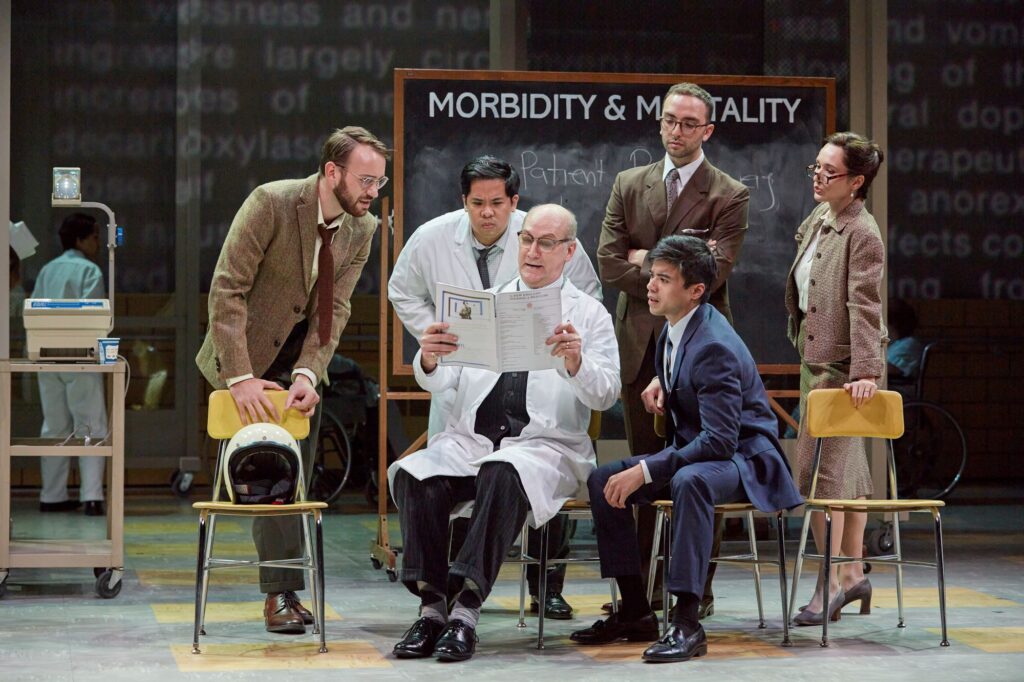

The Opera Theatre of St. Louis world premiere of “Awakenings.” (Photo by Eric Woolsey)

The world premiere of Awakenings at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis was powerfully moving, and so were its three backstories. First: Dr. Oliver Sacks, an eager young neurologist, scarred by his parents’ rejection of his homosexuality and filled with compassion for patients who were closeted from the world for other reasons. Second: the patients themselves, victims of an illness that has been called the greatest medical mystery of the twentieth century. Third: the creators, composer Tobias Picker and his partner Aryeh Lev Stollman, a neuroradiologist, novelist, and now librettist. Sacks was a cherished friend, and they wanted to tell his whole story, at least posthumously. A movie with Robin Williams and Robert de Niro is swell, but Sacks spent most of his life closeted, and acknowledging his own need for awakening would make the medical story all the more poignant as metaphor.

Which is how I watched it. The libretto even borrowed the fairy-tale “Sleeping Beauty” to show Sacks as a would-be prince, eager to rouse patients who sat, inert, watching life through heavy lids and a fog of indifference. Watching them, after his experimental use of L-DOPA, wake up for the first time in three or four decades—elated, adolescent, filled with wonder and burning need—made me think all sorts of thoughts about what it means to be human and alive….

Only briefly did the current pandemic and the mystery of long COVID cross my mind, so caught up was I in the opera.

Afterward, my husband and I went straight to our computers, curious about a worldwide pandemic we had never even heard of. Between 1915 and 1927, encephalitis lethargica tore across the world, affecting at least one million people. It was called sleepy sickness for short, and historians have since found several earlier instances that could well have been encephalitis lethargica. To this day, no one is sure what caused this plague, which killed perhaps half a million people and left others frozen like statues, jerking with uncontrollable tics, or haunted by hallucinations. Huge institutions had to be built to house them. As Sacks wrote, “they would sit motionless and speechless all day in their chairs, totally lacking energy, impetus, initiative, motive, appetite, affect, or desire.”

One theory is that an enterovirus caused the condition, but that is hard to prove without clinical trials. (The pandemic came to a sudden halt twelve years after it began, and today there are only rare, isolated cases.)

Another theory is that the Spanish flu either caused the illness or weakened some people’s immune systems, allowing the encephalitis to take hold.

Reading this, I swallow hard. There are similarities between the Spanish flu and COVID—its rapid spread and mortality rate; the waves with which it covered the globe. There are also similarities between the “sleepy sickness” and long COVID. And we already know COVID can attack the central nervous system—witness the headaches, the loss of smell and taste. We also know that viruses can make us vulnerable to neurological illnesses—Guillain-Barré and multiple sclerosis, for example. And “long COVID appears to be yet another ghost pandemic,” Dr. Samoon Ahmad writes, “in that it shadows COVID-19 and that its symptomology seems to be similarly nebulous. A paper published in The Lancet described a total of 203 symptoms across 10 organ systems.”

Unable to brush aside a creeping sense of doom, I google “encephalitis lethargica AND long COVID” to see if anyone else is worried. Up comes a “call to arms” in the October 2020 Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, urging the neurological community to do long-term monitoring and be prepared for a third wave of COVID in the form of parkinsonism, one of the forms encephalitis lethargica took.

Well, I console myself, that was 2020, and no one is talking about such a dramatic and horrible outcome yet.

On the other hand, many patients with encephalitis lethargica seemed to make a complete recovery, only to later—sometimes decades later—develop neurological or psychiatric symptoms that spiraled.

How does that even happen? One possibility is that inflammation enters the central nervous system and becomes chronic, damaging the brain or the nerve cells. Another is that tiny blood clots form around the inflammatory molecules, blocking the free flow of oxygen to the cells and leaving people fatigued, short of breath, and plagued by brain fog. We are not yet sure.

Nor do we know how to prevent further damage.

As the neurologists write coolly, “The current COVID-19 pandemic could provide valuable insights into the effects of viral infections/inflammation in neurodegenerative conditions.” That knowledge, though, will come at a price.

“I am a living candle,” wrote Leonard, one of Sacks’s patients. “I am consumed that you may learn. New things will be seen in the light of my suffering.”

But not fast enough.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.