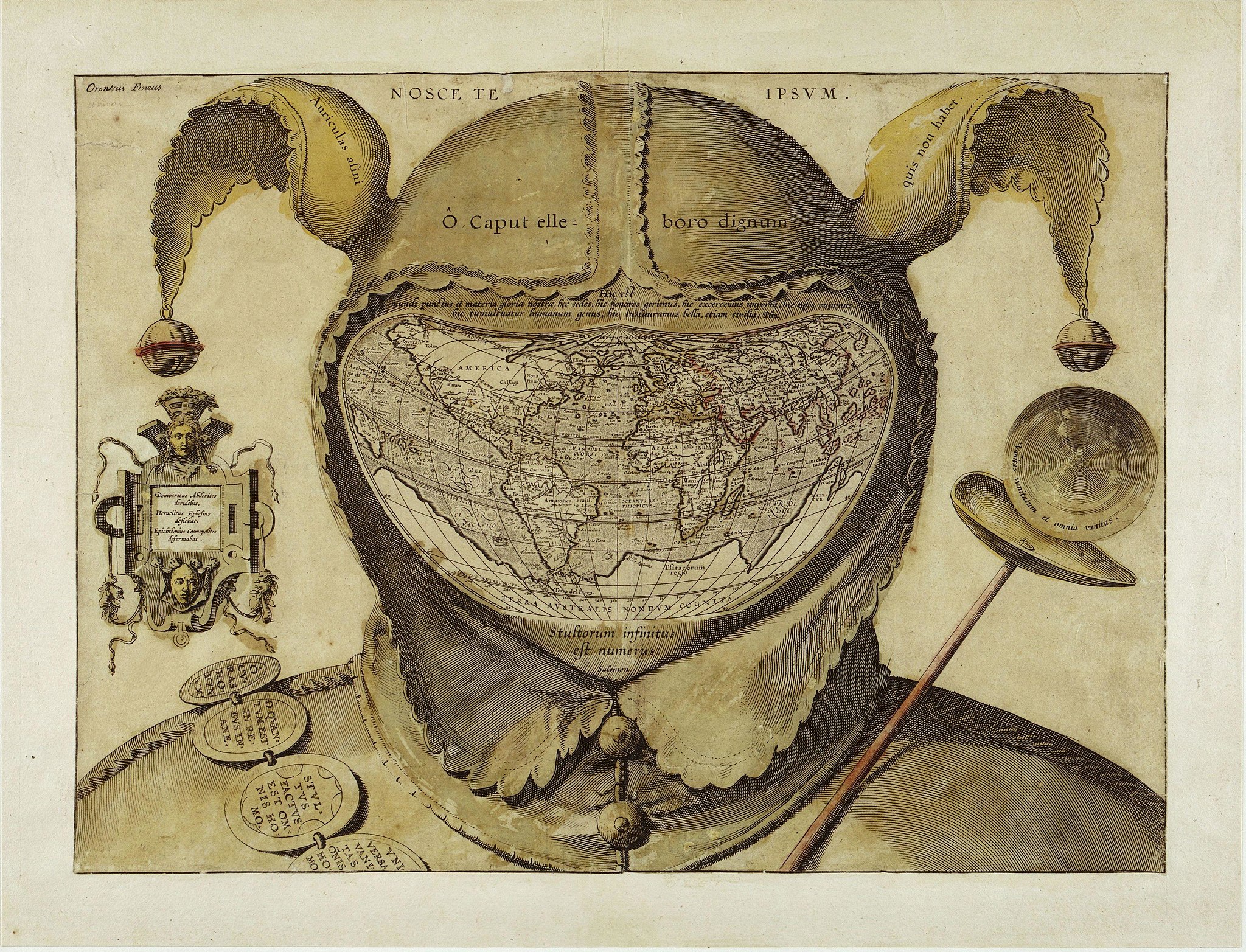

Fool’s Cap Map of the World, via Wikipedia.

After years of fretting about the way the internet is flattening history, stripping away context, jumbling bits of every culture…I have found a book that makes me glad of it.

Affinities is a gorgeous journey through ten years of images in The Public Domain Review. Images that belong to all of us, snatched from ships’ logs, Renaissance woodcuts, antique maps, museum catalogs, primers on Victorian magic, science texts that now sound like fairy tales, fairy tales that never lost their relevance…. Adam Green, cofounder and editor of the PDR, pored over all these images and then began pairing and grouping them. Not by chronology, but by shape or symbolism or topic or mood. He speaks now of the fun of “embarking on long and winding skirmish raids into online repositories with a very specific brief, e.g. to find an image of ritualistic objects parcelled out on a surface, or an agricultural image containing serpentine forms.” Still, it was a herculean labor and an unusual one at that, combing through the past to find the tiny joins and hinges, the recurring motifs and universal symbols.

An antique sketch for a portable camera obscura stands opposite an Odilon Redon lithograph of a single eye, inspired by the eye that followed the narrator’s every move in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” A shiny and sensuous drawing of a mirrored ink stain, done by Victor Hugo (who made more than four thousand drawings, yet all I knew of him was Les Misérables, so I owe him an apology in the next world) takes its place across from a drawing of telepathic lines of communication in a 1907 psycho-therapy textbook and a labyrinth made of lines from the Book of Proverbs.

One of Green’s favorite pairings is a marbled endpaper, on one side, and on the other, a tattooed man. The images mesh—the textures, the soft marbled colors and sepia photo, the use of ink in both. And then you look at the captions and find that “the man is a German stowaway photographed on Ellis Island before being deported, a fact which brings the sea-like pattern in the endpaper to the fore…. And then we see that the endpapers are for a 1640 play called The Noble Stranger,” Green continues, “a title which plays off the immigration history of Ellis Island and this rejected stowaway in particular.”

Coincidences hold untold meanings. You could contemplate just one of these pairings a day and have interesting thoughts for a year. Whoever imagined an affinity between sea corals and fireworks? Yet the minute you see the images, the parallels register. Same with sliced-open gemstones and dissected kidney stones.

I love the double-page spread of “The Fool’s Cap Map of the World,” likely made in 1590 and showing the world as a jester (nothing changes). The continents are framed with wisdom in the form of classical and biblical mottoes, and across the top is the Latin version of the Greek adage “Know thyself.” Know thyself to be a fool? Why not? The pages placed before the map are woodcuts of The Dance of Death and a 1558 painting of the Wheel of Life. The pages after the map are woodcuts, many drawn by a young Albrecht Dürer, from a German satire called Das Narrenschiff, The Ship of Fools. Also a bookwheel drawn in 1588, borrowing the gears of an astronomical clock to create a little cartwheel of books for any scholar tormented by gout. The books spin round and the scholar sits at ease and stares straight ahead; it is the height of ergonomic design. Or is it folly?

In a thoughtful foreword, D. Graham Burnett, a historian of science, says Affinities offers “a gentle revision of the pseudo-Einstein quip: perhaps the real reason for time is so that everything has an opportunity to find everything else. Images need a matchmaker, though, and Adam Green has had great fun with this book, sometimes gathering by categories that recur through the centuries (the body, animals, the moon, various inventions and machines, monsters and deformities, animated flowers) and sometimes juxtaposing in ways that make you catch your breath in surprise.

Paging slowly, almost reverently, I felt more than the curiosity Affinities does such a good job of provoking. I felt, to my surprise, peaceful. We have all been asking the same questions, living with the same flaws and troubles and joys, for centuries. Patterns cross cultures, eras, continents. Symbols never die. We wonder; we dream up weirdness; we build and create. As a species, we hold more in common than it might seem in today’s fractious culture.

“The glory of Affinities,” Burnett writes, “is the way it both is and isn’t in the grip of our moment.” Its images carry us into deep history, yet what were the odds, without an internet, that most of us would see any of this? We could have lived trapped by our own time, oblivious to all those eerie connections and rhymes and echoes. Instead, we can play in the vast database of human artifacts.

I pause on a 1920 drawing of the movement of pain that is grouped with Dürer’s The Man of Sorrows, a hand holding a scorpion, a design for a fortress, and a brilliantly colored painting, on a black background, of scintillating scotomata (migraine auras). Then I flip to pages showing elaborate memory theatres and mnemonic devices, one a gorgeous grid of squares, colors, and symbols that allows memories to be fastened into place and cross-referenced.

I have little need for mnemonics at the moment, though. These images blaze a place for themselves in my brain—and they come with a bonus, a reminder of how many bits of culture connect to each one of them. Affinities even numbers the images in a code that lets you break the linear progression and follow alternative trails.

What was a French Franciscan monk doing illustrating the Kabbalah in 1536? Who knew there were relief globes made for blind children? Or that a children’s book was written about the travels of a bullet, and a “cat piano” was devised by some sadist who envisioned pinning down the cats’ tails and using their yowls of pain as melody? We see the Bank of England in ruins and the Louvre in ruins; we see Goya’s warning that “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.”

This is not the flattening I feared. This is a way to learn from the past as it intermingles with the present. And images this gorgeous and charged will not stay context-free for long. They make you burn to understand them.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.