Three on a Match, or How the Other Two Die

Recalling the intersection of Truman Capote, Perry Smith, and Philip Seymour Hoffman

January 30, 2026

Three men white-knuckled, each clutching his own knot in a long climbing rope. Each senses the weakness of the man in front of him, knows not only when but why he stumbles. They are more alike than any of them care to admit.

The first to die is Perry Smith, executed more deliberately, but just as coldly, as he killed. His death will haunt the second man, the writer who has been working to tell his story. In Cold Blood’s brilliant blend of literary flourish and fact do, as its editor predicted, “change the way people read.” But Truman Capote’s work will never again rise to excellence. He will slump toward his own death, nineteen years later, in a fugue of painkillers, barbiturates, and seizure medications.

The third man, Philip Seymour Hoffman, will capture the second’s inner anguish for the camera, working so surely that you hold your breath as you watch. A big guy with a resonant voice, Hoffman will convince us that he is short, with a squeaky voice, and Southern, and gay, and has fallen half in love with a killer. Capote will win him an Academy Award, and the glow of his feat will linger. Yet like the other two, he will die young—just forty-six years old—surrounded by heroin, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and amphetamines.

Though their lives wound up linked, these three men could not have been more different. Smith was as poor as used-up dirt. Capote sparkled like diamonds and partied with stars: Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra…. Hoffman landed in the shy middle, living off his talent as simply as one can in New York. What they shared was a sensitivity too raw to hide, and pain that sent them running.

Is that enough to explain their deaths? And do I dare call a man who slaughtered an innocent family for less than fifty bucks “sensitive”? Smith was hung at the order of the state, the ultimate punishment for an incomprehensible crime. The other two punished themselves, inexplicably. Unlike Smith, they were deeply loved and widely admired. Yet they lived so self-destructively, toward the end, that the question of accidental overdose or suicide became moot. Not one of these three men felt safe in their own skin, good enough, easy in the world.

• • •

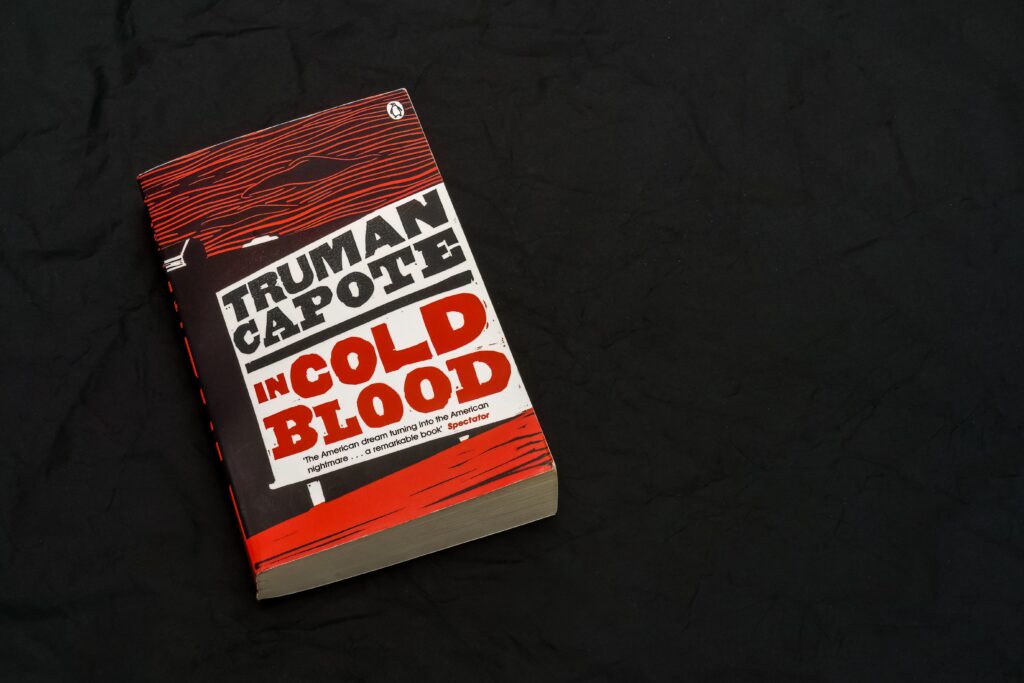

I missed Capote when it was released, saw it recently on a long airplane flight. It held me spellbound; I even waved away a free ginger ale. Now I keep thinking about In Cold Blood, which was assigned to us in high school by a cool ex-nun, and which I, sheltered and demure, shocked myself by loving. And then forgot about.

Forty years later, that book’s influence finally dawned on me. What did I go on to do? Journalism. What sort? The narrative sort Capote helped introduce. What topics did I gravitate toward? Murders so shocking, people’s worldview was rocked, their notions of truth and justice tossed into midair.

By now I know that much of In Cold Blood was invented, in the sense of liberties taken, dialogue imaginatively recreated. Capote bragged of 95 percent recall, but he inserted entire scenes, skidding past the critics with a clever new label, “the nonfiction novel.” What we all later struggled to do ethically—report using literary techniques, dialogue, scene-setting, a narrative arc, symbolism—he did with a blithe disregard for fact.

I find I do not care.

Truman Capote smashed the midcentury expectation that a boring recitation of fact was the only possible approach to the events of the day. He elevated what had come before all that boredom—those lively nineteenth-century reports laced with whiskey, bigotry, and sensationalism—into calm, elegant, intelligent prose. Armed with today’s cynicism, you read his touching passages about the tenderness the sheriff’s wife felt toward Smith, how he reached his hand to her at the end and confessed his shame, and you snort, sure it never would have happened. You reach his final scene, the detective in the cemetery at last finding a sense of peace, and roll your eyes. Yet the detective did reach peace, just not as cinematically. And that tenderness was felt—by Capote. What I never knew was why, or what it cost him.

Capote bragged of 95 percent recall, but he inserted entire scenes, skidding past the critics with a clever new label, “the nonfiction novel.” What we all later struggled to do ethically—report using literary techniques, dialogue, scene-setting, a narrative arc, symbolism—he did with a blithe disregard for fact.

Did In Cold Blood pave the way for the current mistrust of any journalism that does not bore the reader? Please. Truman always lied. He called it “making something come alive.”

• • •

Truman Streckfus Persons comes into the world through the legs of Lillie Mae Faulk Persons, a glamour seeker too young and too restless for motherhood. Somehow, when she snagged Archulus Persons—older, successful, her ticket out of a small town—she did not expect a pregnancy to follow. When it did, she debated an abortion. Does her little boy find out? With all those Southern relatives living close and judging, probably. Lillie has brought her swaddled son to a gothic household of older, never-married relatives and left him there.

She divorces Archie, changes her name to Nina, and eventually marries Joe Capote. She then retrieves her son—on and off. When he is with them, Truman wakes every morning dreading night, when he will be locked in the hotel room so Nina and Joe can go out drinking. They warn the hotel staff not to let him out when he screams, and boy, does he scream. He will later remember most of his childhood “as being lived in a state of constant tension and fear”—which, even if it is one of his exaggerations, is true to him.

Still, Joe Capote is at least there. At age twelve, after Joe formally adopts him, Truman draws himself up and writes to the biological father who broke promise after promise, “I would appreciate it if in the future you would address me as Truman Capote, as everyone knows me by that name.”

Random violence has shoved its way into a place where everybody lives by the same rules and has felt safe because of it. Impulsively dialing his editor at The New Yorker, he announces that this will be his next story, and he needs to go to Kansas as soon as possible.

He grows up and begins writing novels, and he keeps writing letters, many of them airmailed from Europe. They are filled with appreciations of beauty, nature, and art—and cut by sharp criticism of various books, plays, and anyone he felt had slighted or bested him. (W.H. Auden is “a tiresome old Aunty.”) Capote lavishes a needy affection on his friends, using such playful endearments as Blossom Plum or Sweet Magnolia for men and women alike. He offers staunch support to those he loves and clever, gossipy insults for their enemies. He accepts his friends’ flaws, vices, and life mistakes without censure, and he is as frank as a child about his pathetic need for their love. Recovering from a tonsillectomy, he writes, “Do send orchids, and a little love.”

His first successes come from novellas, short stories, travel essays, and the wistful frivolity of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. But one day, he reads a newspaper article about the horrific murder of a wholesome, upstanding family in a small Kansas town. Random violence has shoved its way into a place where everybody lives by the same rules and has felt safe because of it. Impulsively dialing his editor at The New Yorker, he announces that this will be his next story, and he needs to go to Kansas as soon as possible.

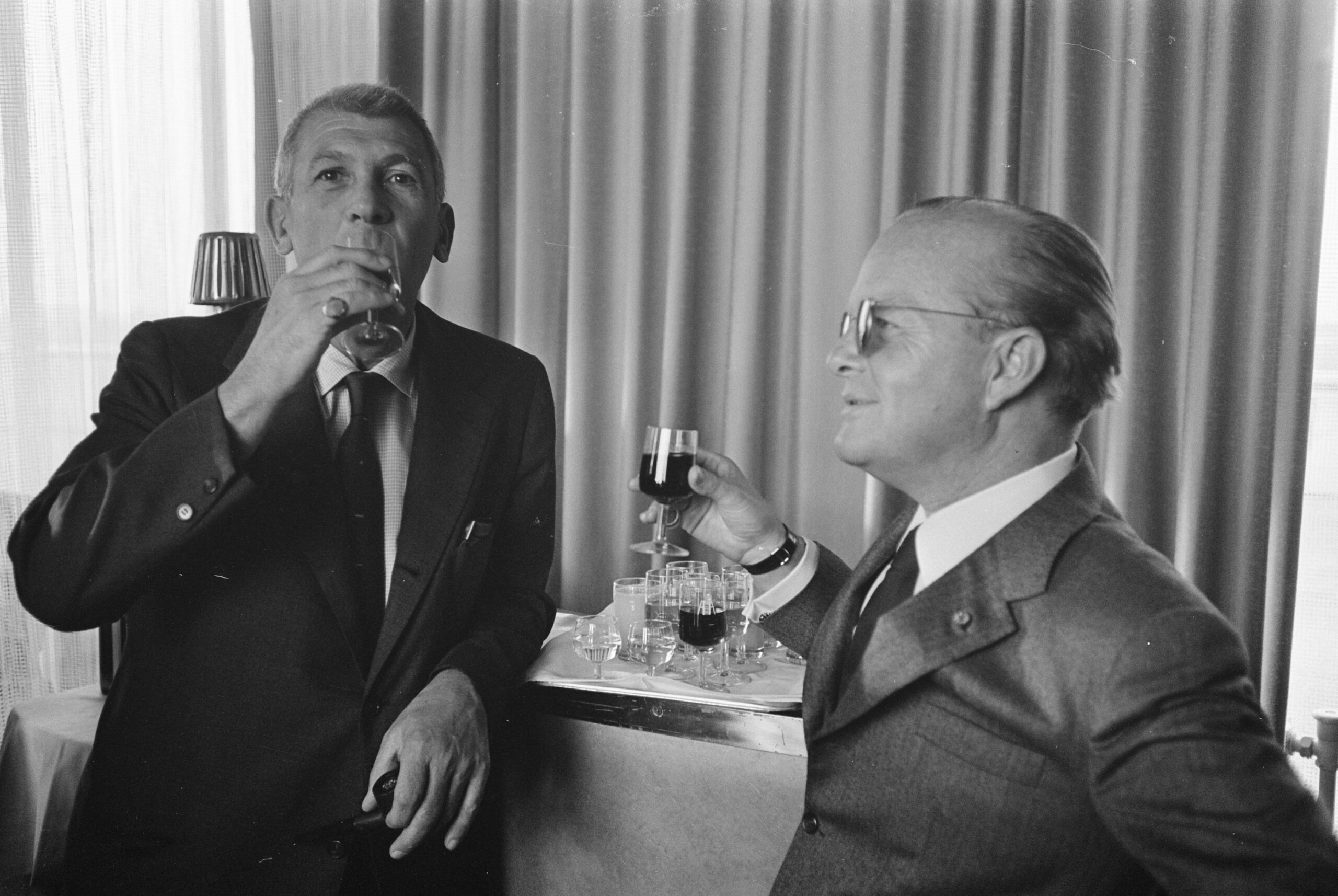

Truman Capote, the fey, elegant, southern-drawled now–New Yorker one imagines with a champagne glass in one hand, parachuting himself into Kansas?

Actually, he takes the train, bringing along his childhood friend and fellow writer, Nelle Harper Lee, to help with research. The killers are still at large; Perry Smith and Dick Hickock will not be captured for another six weeks. When they are finally brought in, it is Smith who captures Capote’s attention. He is drawn to Smith’s brooding, enigmatic silence; his obvious pain. Capote recognizes those scars, and the residual fear, of abandonment.

Mainly, though, Smith is short. Almost as short as Capote himself. A motorcycle accident warped his legs, leaving him in constant physical pain and only 5’4”. “Look! His feet don’t touch the floor!” Capote whispers to Lee at the arraignment, not bothering to hide his glee. “When he stood up, he was no taller than a twelve-year-old child,” Capote will eventually write, never mind that he himself is an inch shorter.

The two men are close in age as well: Smith is 31, Capote 35. He makes note of Smith’s soft voice, small feet, and “girlish hands,” and of a handwriting “abounding in curly, feminine flourishes.” Either he is simply recording careful observations, or he is trying to soften a killer—and if the latter, is it for our sake or his own?

He resonates with this man. He and Smith both kept notebooks growing up, aspiring to a literary life. Capote alchemized his musings into fiction, then further disguised its revelations with a froth of scandalous wit. Less adroit, Smith never managed the camouflage. But he still uses a notebook, saving words he deems worth remembering. (Among them: “dyspathy—lack of sympathy, fellow feeling…facinorous—atrociously wicked…hagiophobia—a morbid fear of holy places & things.” He possesses, Capote will write, “the aura of an exiled animal, a creature walking wounded.”

Convinced that Smith is gentle and soulful, with a deep but thwarted intelligence, Capote pores over the psychiatric evaluations. One comes from Dr. Joseph Satten of the Menninger Clinic, who has previously described this type of murderer: someone who can seem rational yet act senselessly, all ego control dropping away to let a primitive violence, born of earlier trauma, escape. “These men end up puzzled as to why they killed their victims, who were relatively unknown to them. In each instance, they seemed to have lapsed into a dreamlike dissociative trance.”

Pressed repeatedly by Capote to describe that night, Smith finally says, “I sure Jesus didn’t want to go back in that house. And yet—How can I explain this? It was like I wasn’t part of it. More as though I was reading a story. And I had to know what was going to happen.”

Satten’s other observations fit, too: such killers “had ego-images of themselves as physically inferior, weak, and inadequate.” Most important, they had been exposed to extreme stimuli before they were old enough to master them. Their defense was to stop feeling: they had “shallow emotions regarding their own fate and that of their victims. Guilt, depression, and remorse were strikingly absent.”

He resonates with this man. He and Smith both kept notebooks growing up, aspiring to a literary life. Capote alchemized his musings into fiction, then further disguised its revelations with a froth of scandalous wit. Less adroit, Smith never managed the camouflage.

This absence of emotion is so alien to Capote that it never seems to sink in. He, after all, was precocious enough to see his parents’ inconsistencies clearly. He was protected in childhood by a gentle, childlike aunt who adored him, and later by close friends and a loyal partner. Nobody ever loved Perry Smith that fully. And so he turned inward, while Capote’s emotional life bubbled forth. Granted, he can freeze those emotions to get what he wants or stopper them if they scare him, but he feels, to the quick. And despite all the breezy wit and playacting, his sensitivity never calluses.

Instead, all that anguished self-doubt, hyperawareness, and acute empathy will send him to the drugs that eventually end his life. The same will be true for Hoffman, whose work is made of empathy, and who can let no one’s pain slide off. Smith is the tough one—and the only one who, despite all he has done and all that has been done to him, will go to his death still wanting to live.

This is hard to reconcile.

• • •

Perry Smith spends a lot of his childhood in an old truck, crammed against his sisters and brother as they travel the rodeo circuit with their parents. Flo Buckskin and Tex John Smith are alcoholics tricked by booze into violent fights. Periodically, they dump their kids at an orphanage, where Perry’s bedwetting earns him beatings by the nuns.

Flo’s drinking increases, just as Nina Capote’s will, and she chokes to death on her own vomit, unable to breathe through the wet mass of it. (Nina, more conscious of appearances, will swallow sleeping pills.) Perry’s father takes him and leaves the other kids with relatives, then feels so guilty, he will later rationalize, that he starts “roaming to forget it all.” To a parole board, he will describe Perry as “very touchie, his feelings is very easily hurt.”

Without warning, the boy explodes in temper. He is quick to feel cheated, insulted, or disrespected—but while this will strike midcentury psychiatrists as a “paranoid trait,” I am willing to bet that Perry’s appraisal is often accurate. He is scrappy, always fighting to get what he wants, but never convinced he will succeed. Truman, as a little boy, knows he can get his way. Smith never finishes third grade. Capote’s first job is at The New Yorker. He knows how to charm—editors, sources, and the friends who are his lifeblood. “I miss you 25 hours of the day,” he will write, sending “as many kisses as there are scraps in a crazy quilt.”

Smith is just as canny, instinctively aware of other people’s needs and weaknesses, but he uses this knowledge childishly, cajoling or withholding in a pout. Superstitions carry him through each day: you must avoid what you know to be bad luck. Nuns, for example. Nuns are bad luck. A fatalist, he sees the suicides of his sister and brother as proof of the family’s “curse of bad luck.” He tells Capote, “As long as you live, there’s always something waiting, and even if it’s bad, and you know it’s bad, what can you do?” Does he feel helpless because his life has been so hard, I wonder, or because he knows he cannot control the impulses that rise up in him? The two are inextricable.

Capote never feels helpless—at least, not until the end. He remains “the little boy who could work his way out of any sticky situation,” his aunt will recall, with a jaunty walk and “carrying a monstrous Webster’s dictionary under one arm.” Near the end of his life, he will tell her, “I really want to start, literally speaking, a new life,” and she will sigh. “Truman, there is no such thing as a ‘new life.’ Only the turnings and windings and broadenings of the old.”

Smith, the shrinks say, has “an ever-present, poorly controlled rage.” In Capote, rage is less obvious. But how could he not feel it, after his own mother screamed at him daily, horrified and disgusted by his homosexuality?

“You are wrong, Tiny,” he will insist. “There is a new life. And I intend to find it and live it.” The son of a dilettante, he has grown up sure that he has a god-given right to play and to dream. Smith knows instinctively how to dream but has no idea how to play. Instead, he alternates between small, slight pleasures and oversized, unattainable ones. He loves root beer, maybe because its cold foamy sweetness covers the bitterness of the three aspirin he chews to ease the pain in his legs. He smokes Pall Malls and pores over maps, fantasizing about sunken treasure or sailing off on an exotic voyage. Until jail, he fancies himself a roamer marked by “the curse of the gypsy blood.”

Smith, the shrinks say, has “an ever-present, poorly controlled rage.” In Capote, rage is less obvious. But how could he not feel it, after his own mother screamed at him daily, horrified and disgusted by his homosexuality? He convinces his high-society swans to tolerate what is still considered an aberration and a crime, and he delights them with his double entendres and tiny jolts of frank vulgarity.

But now he has a chance to write about a small Midwestern town, packed with Christians who share a single, smug world view, that is shattered without warning. The quintessential American family—man and wife, son and daughter, all of them living as they should—slaughtered for no reason. After dutifully and cheerfully pleasing God in all the prescribed ways, people have had their sense of safety ripped away, with only terror to replace it.

Irresistible.

• • •

There is a fourth dead man here. Herbert Clutter, “a man’s man” by Capote’s reckoning, broad-shouldered, a pillar. “Always certain of what he wanted from the world, Mr. Clutter had in large measure obtained it.” And that included wealth. Hickock had heard that $10,000 was kept in a safe in the Clutter house, and that sparked his scheme. Back at the Kansas State Penitentiary, Hickock had initially dismissed Smith as a sentimental dreamer and “such a kid,” always wetting his bed and crying in his sleep. But one day Smith casually mentioned, hoping to impress him, that he had once beaten a Black man to death with a bicycle chain. It was a complete fiction, but it worked: Hickock looked at him with fresh interest.

Now here they were.

When Smith realized that the tipoff was wrong, and the only cash on hand was the stack of small bills they had yanked from wallets and purses, he wanted to leave. But as he knelt over Herb Clutter, whom he had made comfortable on a mattress because the basement floor was hard and cold, humiliation flared, supercharged by every shame he had ever felt. The pain of kneeling lit his nerves on fire, and he felt Clutter looking at him “like he expected me to be the kind of person who would kill him.” So he took the knife Hickock handed him and slit Clutter’s throat.

“I didn’t realize what I’d done till I heard the sound,” he would say later. “Like somebody drowning. Screaming underwater.”

In writing In Cold Blood as he does, Capote is erasing the automatic wall between two killers and Middle America. No matter how badly we want to, we cannot distance ourselves. But to pull off this trick of empathy, Capote has to come as close as possible.

When Clutter refused to die, Smith shot him in the head. He will at one point confess to killing all four of the Clutters himself, telling Capote he does not want Hickock’s parents to suffer any more than they already have. No one much cares if this is true; both men will hang.

As he waits in jail, Smith watches through the window as cats hunt for dead birds caught in the cars’ grilles, hating it “because most of my life I’ve done what they’re doing.” A scrounger and an outsider hungry to belong and be celebrated, he pores over the newspaper article about the Clutter funeral, impressed that a thousand people came and curious how much the funeral cost. When an old Army buddy, a Christian, comes to visit, Smith volunteers, “It wasn’t because of anything the Clutters did. They never hurt me. Like other people. Like people have all my life. Maybe it’s just that the Clutters were the ones who had to pay for it.”

You shudder—but you keep reading. In writing In Cold Blood as he does, Capote is erasing the automatic wall between two killers and Middle America. No matter how badly we want to, we cannot distance ourselves. But to pull off this trick of empathy, Capote has to come as close as possible. He pays the attention Smith craves, offers legal help and respect and what seems like caring. They are using each other, Smith dangling the facts Capote needs, Capote feigning an alliance that is really only a book project. Except that the similarities between them get under his skin, and a transaction turns into an uncomfortable friendship, after all.

Smith’s death derails him.

• • •

“After the drop, they go on living—fifteen, twenty minutes,” Capote blurts after the execution he had to be pushed to attend. “Struggling. Gasping for breath, the body still battling for life. I couldn’t help it, I vomited.”

He begins to live recklessly, unable to concentrate on new projects, divided between an adult self and the boy Smith reminded him of. Sensitive, hurt, unprotected, abandoned, grandiose, alone.

Capote spends the 1970s in and out of rehab clinics, in thrall to the drugs and alcohol he once pronounced ruinous to the creative life. “The proximate cause of his tragic fall—for that is what it was—was In Cold Blood itself,” writes Capote’s most thorough biographer.

“No one will ever know what In Cold Blood took out of me,” Capote himself remarks. “It scraped me right down to the marrow of my bones.”

In 1977, he has to be led off the stage at a reading. In 1981, he is carried, comatose, out of his apartment. And in August 1984, a month before his sixtieth birthday and the fabulous party Joanne intended to throw for him, he goes to his room at her Bel-Air mansion for a nap, and his body starts to shut down.

The official ruling is “liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication.” But the overload of drugs in his system easily could have disrupted the rhythm of his heart, and if Carson had called for an ambulance, he might have been saved. He begged her not to. “If you care for me at all, let me go.”

• • •

Capote opens with a schoolgirl discovering her friend’s family, murdered. Then the film cuts to Manhattan, with Capote—the slight lisp, the high squeak—holding forth at a party, the guests hanging on to his every word. Hoffman even manages to look like him. There is that same mix of innocence and cultivated persona; that same upward tilt of the jaw, not quite belligerent but daring the world to stop him—and at the same time begging the world to love him. Hoffman is showing us, at once, Capote’s performance and the pain beneath it.

He captures the way Capote slouches toward Nelle Harper Lee in the train compartment, needing her steadying presence. He captures Capote so drunk and despondent, you want to slap him out of it. Hoffman captures that. Puts no happy gloss on it, no romantic glow, just shows the pathos and lets us despise it.

Then, less than a decade later, he lives it himself.

• • •

Hoffman’s mom was a family court judge. She and his dad divorced. Philip was bookish and introspective as a kid. And that is as bad as it gets, at least on paper. He finds his passion and, despite looking nothing like the sought-after leading man, becomes a luminous success. He is in love with his wife and kids; his siblings and friends cherish him. Subtract the sensitivity, and he has little in common with the first two men—except that he is such a consummate actor that he enters Capote’s soul. Once inside, he shows us what would otherwise be hard to imagine: Capote’s fascination with Smith, how useful it is but also how painfully honest.

Also, like Capote, Hoffman has found relief with drugs. Is Perry an addict? He has never killed before. His only painkillers are dreams and aspirin. His cravings are for adventure, attention, acceptance. His self is the least formed of the three, yet with the exception of one night’s bloodbath, he is the least self-destructive.

What diabolical mix of genes and life pushes someone into addiction? How do two men of immense talent wind up in its thrall, while a damaged killer still holds hope—that fragile emotion—for an impossible reprieve? These three men pace back and forth in my mind. Why do I care about their various similarities and differences? I thought this would be a remembrance of journalism, but now I realize: it is the unnecessary deaths that caught me.

Three friends I cared about, all men of intelligence and sensitivity, killed themselves—or, an uncertainty that haunts me even more, screwed up so miserably that their deaths looked intentional. And substances were involved every time.

I can pick out failures that preceded their deaths, just as I can for Hoffman, sitting next to his ten-year-old son at the Academy Awards and failing to win, or Capote, his movie script rejected. But any artist faces periodic rejections. What stung these two—and my friends—was self-criticism. To escape it, they used any substance within reach, scrubbing like a kid does with a pink eraser.

Both Hoffman and Capote had been to rehab. But once you feel there is a substance that will ease your pain, that lie rings true again and again. You can buy yourself minutes or hours of oblivion. Like Truman’s little lies of creative nonfiction, the lie hints at underlying truth—but twists it.

• • •

Just as In Cold Blood changed the way people wrote, Hoffman’s performances changed acting. He chose parts that involved the sort of damage and outsider vulnerability that is easy to caricature, then refused to do so. He also refused to simplify emotion, instead showing it subtly, in a flicker of shame, a caught breath, a tightened muscle or a twitch at the jawline. Always, he exercised a powerful restraint—as did Capote, in prose that refused to explain or emote. Their work stayed calm, gliding through ambiguity and contradiction. “Anyone consistently consistent,” Capote once remarked, “has a head made of biscuit.”

Both men were accustomed to feeling too much; they knew how to pull the emotion back because that is what they had to do every day. They met their art differently, though. What Hoffman did in acting was hand off his ego, reveal his own discomfort and shame. What Capote did in ink was polish his ego, using art to hide his insecurity and wit and glamour to gild it. He hid pain beneath beauty; Hoffman revealed pain by stripping beauty away. One man lived with a radical emotional honesty, the other with invention and persona and aesthetic stylization.

Yet they landed in the same despair.

Neither death was technically a suicide. But were they deliberate acts of self-destruction or desperate, unthinking attempts to end intolerable pain? Did Capote mean it when he asked Joanne Carson to let him go, or was he just glazed, dopey, and used to the habit of melancholy? Did Hoffman register how much heroin he was pushing into his veins and think, what the fuck, or was he too far out of it to even know?

What Capote did in ink was polish his ego, using art to hide his insecurity and wit and glamour to gild it. He hid pain beneath beauty; Hoffman revealed pain by stripping beauty away.

I ask these questions of my friends’ ghosts. One, especially, reminds me of Capote and Hoffman: smart, kind, witty, with a breakaway hit book that was about to be made into a movie. He could not gather the courage to start another book that might not be as good. Hoffman, though—his career was taking off. After his death, John le Carré said Hoffman’s embodiment of Capote was the best single performance he had ever seen. The intelligence shone, he added, but so did the anxiety: “Philip took vivid stock of everything, all the time. It was painful and exhausting work, and probably in the end his undoing…. Philip was burning himself out before your eyes.”

We always know, in retrospect, where a life is headed.

• • •

There are those who are born exquisitely sensitive and who use that gift, turning it into art or love. They charm people into overlooking, or even delighting in, their quirks. We forget how much they are suffering.

Others are incapable of blending in, pretending to be one of the gang. Stubborn in their sensitivity, they gather up all the ways they are different and use them to constantly remind the world of its cruelty. And sometimes they adopt that cruelty themselves, as revenge.

After Smith’s arrest, he asked eagerly, “Were there any representatives of the cinema there?” Hoffman shrugged off fame, showing up at awards ceremonies and premieres unshaven and shlumpy and only when he had to. Capote bathed in fame like it was a tub of melted chocolate, but he also saw that it was a trap. In Interview magazine, he wrote that in his next life, he would like to be a buzzard, because “a buzzard doesn’t have to bother about his appearance or ability to beguile and please; he doesn’t have to put on airs. Nobody’s going to like him anyway; he is ugly, unwanted, unwelcome everywhere. There’s a lot to be said for the sort of freedom that allows.”

Capote’s whole life was a performance, a self-creation like his mother’s. Hoffman was the opposite, open about his flaws, honest, willing to confess addiction even to a stranger in a bar. But both men were relentlessly self-critical. Capote might have sounded grandiose, but he was never sure that what he did was any good—or if it was, that he could repeat it. Hoffman would thank people for compliments and swallow what he wanted to say next, which was, “You’re wrong.”

In “Shut a Final Door,” Capote writes, “All our acts are acts of fear.” Yet what he and Hoffman shared more obviously was a radical insecurity, as though they moved through the world on stilts, reaching great heights but with their balance always precarious.

Smith? He had never done anything worthy of critique. The irony haunts me: this man, whose only “contribution to society” was the slaughter of an innocent family, and whom most of the country wanted dead—wanted to live. Was elated at each delay, begged for a good lawyer, pressed on. Did his fantasies give him a childish, disconnected hope that the other two, saner and far less damaged, had long ago seen through? Why—that childish question I cannot escape—did they have to be the ones to die? Was the intensity with which they lived impossible to sustain? Was the empathy too painful or the ego too fragile? Or did the chemistry just overwhelm their bodies, and therefore their minds?

No writer should use such a succession of question marks; it erodes the authority of the prose. Yet I have nothing but questions. In “Shut a Final Door,” Capote writes, “All our acts are acts of fear.” Yet what he and Hoffman shared more obviously was a radical insecurity, as though they moved through the world on stilts, reaching great heights but with their balance always precarious. They could not grow a thick skin, convince themselves they were content, fulfilled, enough. They needed their restlessness, empathy, and vulnerability in order to be who they were. They needed a certain kind of ego, too—not combative, they were too inward for that, but hungry, propelling them to the next project and the next.

Hoffman’s wife, Mimi O’Donnell, dismisses one explanation after another—being a child of divorce, pouring himself into an emotionally exhausting performance in Death of a Salesman, losing his longtime therapist to cancer—and lands on the “cunning, baffling, powerful” force of addiction itself. Would it have taken him over if he had become a plumber? Maybe; who knows why some people get past addiction while others cannot? But all that public attention is an exacerbation, as is the intensity of living out other people’s pain. Hoffman’s mother, Marilyn O’Connor, worries now that his son Cooper is acting, because she knows “the life that follows…. It’s not always the best thing to happen to somebody.”

Of the two, Capote’s death initially struck me as easier to understand. He could never feel loved enough, and he spent so much energy lacquering his persona that he imagined it a relief to be a buzzard, free from the need to try. Anyone might turn to substances to ease pressure that relentless. But Hoffman’s life, despite the exhaustions of self-doubt, empathy, and celebrity, held a great deal of grounded, genuine joy.

When I voice the comparison to someone who was close to him, though, that person gently suggests that I examine my biases; there is no reason one of these deaths should be easier to understand than the other.

Chemicals can cut across difference and destroy anybody.