How Charles Dickens Panned the United States, Then Paused to Laud It

By Ben Fulton

January 17, 2026

Whatever the arguable truths of U.S. history may be, one fact is plain: Americans care about what other people, especially other Americans, think and believe about our nation’s history.

For proof, witness not just the state of Florida’s recent reconfiguration of its public school history textbooks, but also the current administration’s scolding broadsides against the Smithsonian Institution and texts for National Park monuments. Executive Order 14253, issued in March 2025 and titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” punches against alleged “distorted” narratives of “historical revision” based on “racist, sexist, oppressive” contexts. The restoration of “truth,” then, implicates the erasure of any historical accounts of the Trail of Tears, the Wounded Knee and Sand Creek Massacres, the Tulsa Race Massacre, the women’s suffrage movement, and the driving cause behind our nation’s single most deadly conflict, the U.S. Civil War. All of these events either never took place or were grossly misunderstood.

But set aside, for a moment, arguments about history. There is another nagging problem with any Executive Order insisting that nothing “distorted” be said about U.S. history. It is the problem of opinion expressed and based upon first-hand accounts. It is the problem of competing versions of perception. Long before our current era of rabid populism hyped on fist-pumping nationalism, Charles Dickens excelled in his perceptive powers of the early United States. For anyone who has read Dickens, this makes almost perfect sense. Of course, the master of prose portrayals of individual characters could not help but draw a collective portrait of any foreign country he cared to visit.

Dickens’s first sally was his 1842 account of his six-month trip across the ocean, American Notes (Penguin Classics, 2004, Ed. Patricia Ingham). Over 274 pages, Dickens unfurls his collective impressions of American character—a “magnetism of dullness” pervades Midwesterners and Southerners; Northern Yankees carry “a certain cast-iron quaintness”—even if American women are found somewhat charming in their colorful dress. He is wholly impressed by U.S. universities—“Above all, in their whole course of study and instruction, [they] recognize a world, and a broad one, too, lying beyond the college walls”—but appalled and disgusted by the “odious” American habit of spitting tobacco, or “expectorators.” A boat trip along the Mississippi River reveals little else but the “the changeless glare of the hot, unwinking sky, shone upon the same monotonous objects.”

Leaving Cincinnati on a trip to Louisville, Dickens is charmed by a conversation with Pitchlynn, a chief of the Choctaw tribe of Native Americans. But above all, nothing and no one during Dickens’s trip can dull the pain of injustice he witnesses in chattel slavery. Toward the end of American Notes, Dickens chronicles a litany of newspaper accounts of bizarre acts of violence committed by White Americans, positing that surely these acts are tainted and influenced by the violence that Americans see, but can barely acknowledge, in slavery itself:

… the scenes of action in reference to places immediately at hand, where slavery is the law; and the strong resemblance between that class of outrages and the rest; lead to the just presumption that the character of the parties concerned [in these newspaper accounts of criminal acts] was formed in slave districts, and brutalized by slave customs. (258)

Pages before that conclusion, Dickens surmises that slavery’s malignancy on American character is so deep, yet unconscious, that it infects most social interactions:

Slavery is not a whit the more endurable because some hearts are to be found which can partially resist its hardening influences; nor can the indignant tide of honest wrath stand still, because in its onward course it overwhelms a few who are comparatively innocent, among a host of guilty. (251)

Were Dickens alive today, he would probably laugh in the face of our nation’s current fervor for writing over, as Executive Order 14253 puts it, “a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our nation’s history.” Dickens, like everyone else in the past, present, and emergent future, has eyes to see and ears to hear. Collections of subjective judgments may coalesce and congeal into objective, historical truths, but some are clearly better expressed and articulated than others. As Ingham relates in her introduction to the Penguin Edition of American Notes, Southerners were so appalled by Dickens’s reporting that they worried it might inspire a slave rebellion. South Carolina officials came close to banning it soon after its publication.

To book-end his non-fiction reporting of travels through the United States Dickens, ever the prodigious novelist of Victorian England, could not rest until he also assembled his impressions of our country in a fictional novel as well. Martin Chuzzlewit (Vintage, 2010) published two years after American Notes in 1844, is no one’s favorite Dickens novel. It ranks among his weakest works in terms of character and plot. But as a lacerating examination of nineteenth-century America, it ranks among the best works of fiction.

Sandwiched between a mostly tiresome plot of a family feud around an aging patriarch’s fortune, Martin Chuzzlewit’s best sections chronicle the adventures of the younger Martin Chuzzlewit and his sidekick Mark Tapley as they forsake Old Blighty for a chance at fortune in the New World. Like Dickens, Chuzzlewit finds Americans tiresome, bizarrely insistent that we are, almost to a person “remarkable,” but also contentious, violent, and obsessed by money, or as Dickens writes, “Men were weighed by their dollars, measures gauged by their dollars; life was auctioneered, appraised, put up, and knocked down for its dollars.” (273)

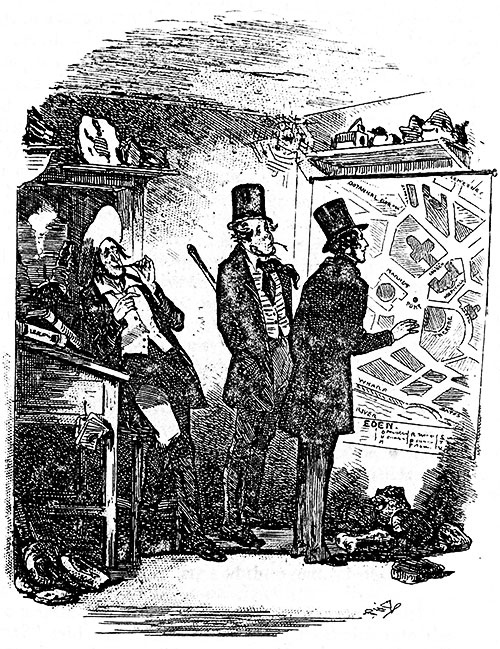

Also like Dickens, Chuzzlewit and Tapley endure the heat and mosquitoes of a trip down the Mississippi, but this time in search of a plot of land purchased in the purported city of Eden, which, in the grand tradition of real-estate scandals the world over, turns out to be nothing more than a mirage.

Shortly before the catastrophe of this swindle, Chuzzlewit formulates a key to American character that, even today, would probably unlock millions of “patriotic” Americans. As is so often the case in our country, panic and paranoia are somehow compatible with unyielding pride:

Martin knew nothing about America, or he would have known perfectly well that if its individual citizens, to a man, are to be believed, it always is depressed, and always is stagnated, and always is at an alarming crisis, and never was otherwise; though as a body they are ready to make oath upon the Evangelists at any hour of the day or night, that it is the most thriving and prosperous of all countries on the habitable globe. (268)

Similar to American Notes, chattel slavery in the United States is never spared its rightful disdain. But as Dickens scholars will readily point out, Dickens himself proved a bigot on his second visit to the United States when, after the U.S. Civil War and the emancipation, he was incredulous at the thought of Black Americans having the right to vote. The English could be justifiably smug about having ended slavery in an act of abolition in 1833, decades before the United States did the same. More embarrassing to answer for is why the British government sided with the Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War. Judging other countries is often easier when you fail to judge your own country more thoroughly. To the detriment of his overall legacy, that bigger view of justice in history never came into focus for Dickens. Little of that, however, subtracts from the many points he scored against our national character.

As Chuzzlewit and Tapley sit in their decaying cabin of Eden by the swamp and sickness of the Mississippi River bank, surrounded by destitute Americans also out to seek their fortune, by who are slowly dying of malaria, Chuzzlewit himself falls ill, recovers to realize the error of his having left England, but also comes to a slow realization of how his trip to America has steeled his soul in ways he comes to appreciate. Having fallen ill beside his business partner Tapley, having considered his own selfishness in his ridiculous attempts to grow rich in America at the expense of his home in England, Chuzzlewit is afforded some difficult views into his own character. Having spent enough time in America, the time for lambasting Americans is over:

Eden was a hard school to learn so hard a lesson in; but there were teachers in the swamp and thicket, and the pestilential air, who had a searching method of their own. He made a solemn resolution that when his strength returned he would not dispute the point or resist the conviction, but would look upon it as an established fact, that selfishness was in his breast, and must be rooted out. … and there was not a jot of pride in this; nothing but humility and steadfastness: the best armour he could wear. So low had Eden brought him down. So high had Eden raised him up. (525)

It sounds simplistic to say that what Dickens is describing is the material of a “character-building experience,” a trial from which the soul emerges stronger. But at long last, Dickens finds something worthwhile in the margins of life lived on U.S. soil. At long last, after turning hundreds of pages, an American reader can delight, even rejoice, in knowing that our country is not altogether bad, and that a powerful force of good resides in our national ideals. If only we had the patience to wait, work, and look for them outside of stern, scolding Executive Orders.

Taken together, American Notes and Martin Chuzzlewit reveal to us not only the fun of laughing at ourselves as Americans, but also the folly of how painfully ridiculous we look when we fail to acknowledge our faults and the collective injustices of our history that we would rather walk past. There is no virtue in unyielding, unquestioned “patriotism,” much less iron-clad nationalism. There is only material for ridicule, waiting for the next outsider with literary acumen to describe and document in cold-eyed prose. There is also no virtue in a country that cannot admit faults. In admitting no faults, we rob ourselves, and every other country outside our borders, of any nuanced view that would make the United States such a rich progenitor of opinions, viewpoints, and multifaceted histories. A place, in other words, upon which a more solid, stable future might be built.