Billy Joel Documentary Like a Good Novel

September 5, 2025

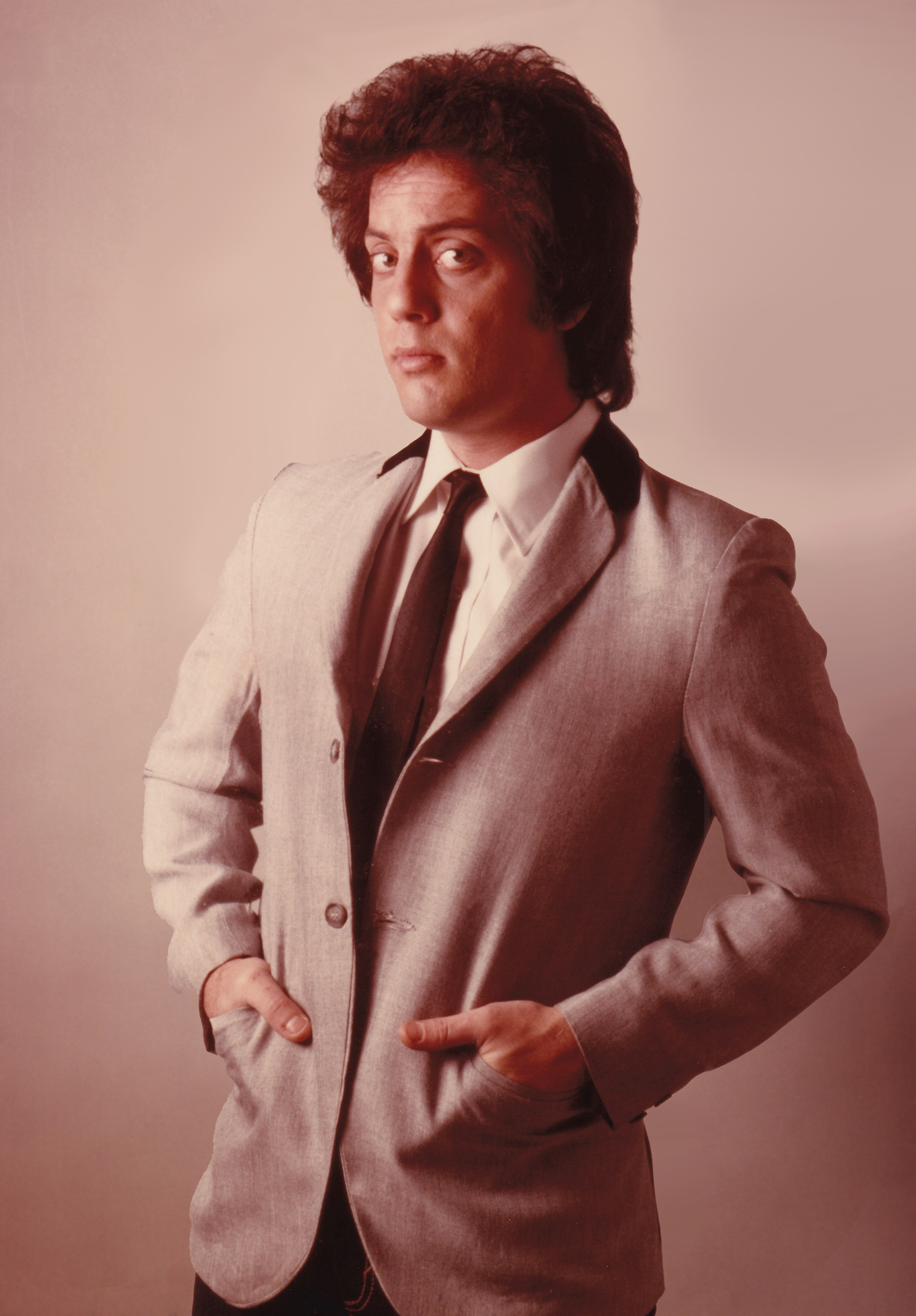

Back in the olden days, we were often at the mercy of local radio, on job sites and in cars, and I listened to a lot of singer-songwriter Billy Joel’s music. I liked it fine, especially his voice and attitude, but I cannot say I was interested enough in him as an artist to pay attention to his life. A recent documentary on Joel turns out to be well worth a watch, even if, like me, you were never a superfan.

Billy Joel: And So It Goes (HBO Max) takes a similar approach to The Beatles Anthology (1995, now being re-released with new material) and Runnin’ Down a Dream (2007, Peter Bogdanovich’s tribute to Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers). These are not just musical biographies at significant length; they contain critical-aesthetic commentary, historical context, explanations of artistic process and business decisions, psychologizing, and the presentation of whole-life conflict in subjects’ lives that might be better described as novelistic. I would watch a well-made documentary in this vein about any subject, even if I did not know their work.

For someone like me, who knows maybe the top 15, most-popular, Joel songs (“Uptown Girl,” “Piano Man,” “New York State of Mind,” “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” etc.), the documentary deepened my understanding of Joel as a living character and of the history of popular music.

For instance, many songs on the radio in his era did not seem to fit genres. “Piano Man” is not rock, and I would not call it a pop song. Many songs by The Beatles, Lou Reed, Leonard Cohen, Elvis Costello, or Randy Newman were this “something else.” The documentary explains the influence of Tin Pan Alley and classical music on Joel, as opposed to rhythm and blues or folk, and I suddenly understood him better.

In the past I did not really register Joel’s alcoholism, his many marriages—and his improbable, winning way with supermodels other than wife Christie Brinkley—or, more interestingly, how he “retired” from writing after 1993. I had seen headlines in the news that he had a “residency” at Madison Square Garden, as if it was his own Las Vegas, but missed that it was 10 years of sold-out shows. I knew nothing about his 16-year concert tour with Elton John, whom he had always resented being compared to.

Joel’s talk of process—or maybe even more, his talk of the difficulties of process—is fascinating. The music often did not come easily. He describes the piano as “a big black beast with 88 teeth, trying to bite my hands off,” but that he had to stick with it to find the song, through moodiness and deep loneliness. After one album did flow, the next, he says, “was like squeezing a lemon.” He was the lemon, trying to make lemonade to the demands of the record company.

One of the reasons I like the term “novelistic” for these sorts of documentaries is that it stresses how they deal in the mysteries of creation, its meaning, and its emotion. Joel has a song from 1977 called “Vienna,” with the refrain, “When will you realize / Vienna waits for you.” Fifteen years ago, Joel said Vienna was a metaphor for old age and how it should be valued, so you should “slow down, you crazy child.” It was released originally as a B-side to “Just the Way You Are.”

But in the documentary, Joel offers other explanations, such as how Vienna was the capital of world music, as he puts it—he was trained in classical music—so if you were a musician, you had to deal with that place. It was also where his estranged father had moved when Joel was a boy, without telling anyone. Joel had to search for him, then re-established what was, at best, an emotionally distant relationship. The last studio album Joel made, in 2001, was classical music he wrote—it was performed by pianist Hyung-ki Joo—and titled Fantasies & Delusions. Clearly, he was trying to connect to both his musical roots as well as his own father, who was trained as a classical pianist. There is a terrible but important moment—the documentarians know what they are about—that shows Joel’s wonder and hurt, still, in old age, that his father never said a word about the album. This moment is one of the most personal and affecting things I have seen in film in a long time.

Joel also learned in his visits to Vienna that much of his father’s family had been murdered in the Holocaust. In a typically perverse twist by the Nazis, Joel’s paternal grandfather’s textile factory was stolen and used to make striped pajamas for the concentration camps.

After the Tiki-Torch Whites in Charlottesville chanted, “Jews will not replace us,” Joel wore a yellow Star of David in concert, leaned out to his audience, and said bitterly, “Don’t take any shit from anybody.”

The documentary suggests at its close that “Vienna” has become a legacy piece for Joel to rival “Piano Man.” Its title symbolizes both beauty and death, not because they are necessary to each other’s meaning, but because they co-exist and must be dealt with. The artist that can dwell in that complexity is always worth a look.