Yes, We Can Be Ambivalent About the Death of Mass-Market Paperbacks

By Ben Fulton

February 7, 2026

Much like floor traders at the New York Stock Exchange, literary types tend toward panic when their beloved landscape of books feels the tremors of change. They often agonize over the dominance of self-help and assorted “trend” titles on best-seller lists. Decades ago, they launched into a slow-motion panic about how books and reading would remain “relevant” without independent booksellers.

Now, when Readerlink Distribution Services announced last December that it would cease distribution of mass-market paperbacks by the end of the year, that locus of anxiety has hit the “dime-store novel,” the “pulp fiction paperback,” the “pocket edition,” or what an aunt of mine even called her “softback flyswatter.”

The announcement by the Oak Brook, Illinois,-based publisher, and nation’s largest distributor of titles to retailers, landed with a particularly eye-popping statistic: Between 2004 and 2024, sales of mass-market paperbacks had dropped 84 percent.

Almost anyone over the age of 40—dare it be said, even 35?—has their own indelible memory of this crafty little reading medium. Maybe your mother went days without sleep to slog through V.C. Andrews’ Dollanger series, starting with the 1979 title Flowers in the Attic. Maybe it was your older brother making his way through Peter Benchley’s Jaws, published one year before Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film adaptation, but which almost no one read before the blockbuster film. In fact, it marked the first time many people embarked on reading their first-ever book, beginning to end. At least, that is how it was with my circle of middle-school friends.

A New York Times feature invited Stephen King, who perhaps more than any other author owes his career to the format, to pronounce his verdict on the development, cloaking the mass-market format in the respectable veneer of “middle-class” pursuits. He even described it as “democratic,” invoking with it the earnest concern surrounding our nation’s political climate.

All of which is fine. If we believe in reading, we must at some level believe in reading whatever medium delivers words, sentences, paragraphs and, hopefully, whole pages constituting chapters. The more reading, the better. Ergo, the more ways to read, the better. But surely this overlooks the constant cycle of hand-wringing every time one format replaces another. Painters lamented the advent of photography. Musicians lamented the gramophone. Before social media reached its pariah status, politicians and parents looked on in horror at the violence in video games that allegedly unleashed school shootings. Maybe civilization is hanging together by mere threads, but if so, they are mighty strong threads, as evidenced by crime rates that nevertheless rise and fall by forces that remain, for the most part, mysterious.

Although many readers collect the format, few of them go so far as to hail paperback books as works of art. Still, Walter Benjamin’s seminal 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” instructs us even today, and then some. It remains, as anyone who has ever read it will tell you, the ultimate word on the interplay between form and content.

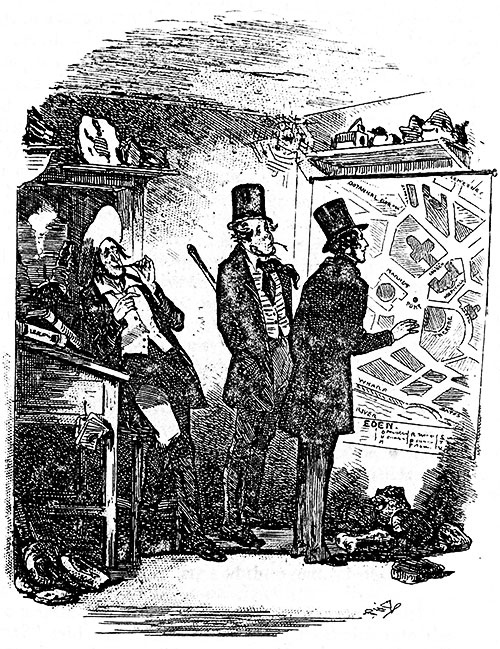

“Technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into situations which would be out of reach for the original itself,” Benjamin writes. “Above all, it enables the original to meet the beholder halfway, be it in the form of a photograph or phonograph record. The cathedral leaves its locale to be received in the studio of a lover of art; the choral production, performed in an auditorium or in the open air, resounds in the drawing room.”

And we are all, anyone and everyone who cares about art and beauty, richer for it.

All that is really lost, Benjamin points out, is authenticity, or what he describes as “the authority of the object,” or “the aura of the work of art.”

For all of Benjamin’s brilliant exposition throughout this essay, we can still complain that he is merely pointing out the obvious. Collectors of fine art know this. Else, why would they shell out millions for an “original”? Book collectors who spend hours sniffing out first editions of their favorite titles know this as well. Stephen King’s esteemed “middle-class” readers know this, too. But is anyone going to pretend they care when words are so easily transposed, whether in hardback, softback, e-reader, or, yes, the soon-to-be-gone mass-market paperback?

For my part, I love the format. Fond memories abound of scouring second-hand bookstores for Viking Portable editions of favorite canonical writers, ranging from the ancients to American modern masters. But those easily gave way to a fondness for Norton Critical Editions. Again canonical, but published with copious treats of complementary background material and famous critical essays on the title text.

The oddest reaction to mass-market paperbacks was, many might remember, the crazy dawn of “leather-bound” classic titles so polished, embossed, and gilt-edged that the reader felt too intimidated to dare pull them from the shelf. The Folio Society did them several grades better, mostly with lavish accompanying illustrations and introductions by noted scholars. But even then, neither producer of hardbacks could quite top the genial comfort of the Penguin paperbacks that graced working-class pockets in the UK from 1934 onward.

Walter Benjamin’s starting point of “authenticity,” strictly speaking, may reside in a first edition book more than the lowly paperback for the “mass market.” But if we believe that either is elevated above or below the other then we have probably missed many lessons we should have learned simply through the act of reading. Objects, in the end, are immaterial. Status is malleable. As for the reading experience itself, how can it cease to be unique and contextual regardless of medium and format?