Why the Line Between Coercion and Consent in Policing Eludes Us

By Ben Fulton

February 13, 2026

We keep a supply of books because we have faith in whatever discoveries they might hold. Such was the case with a copy of Encyclopedia Britannica’s The Great Ideas Today 1983. I have held on to this collection of scientific, literary, and historical essays for years for its inclusion of an essay about the great twentieth-century French historian Fernand Braudel (1902-1985). Weeks ago, I found it also contained the bracing essay “The Idea of Civil Police,” written without a byline but as a group effort by Britannica’s editorial board, assembled under the title of an “Institute for Philosophic Research.”

In no more than twenty pages, the essay promises a grand tour of “the idea of police power and law enforcement” as set forth by Western political philosophers and the history of institutions, both ancient and more recent. It opens with a thunderclap of a claim. Aside from minor exceptions in the Areopagus, a sort of combination of courts and their loosely formed administrators, along with the “aediles” of the Roman republic, or magistrates connecting tribunes and praetors, the essay claims boldly that, “a police force, such as we know one today, did not come into existence anywhere in the Western world until the establishment of the Metropolitan Police in London in 1829.”

This is an astonishing statement, until the reader understands the paramount importance of the word “civil” in “civil police.” Police forces buttressed by the consent of those they vow to serve and protect did not come into being until the dawn of constitutional, democratic republics. The nascent force of officers assembled to enforce the laws of London arrived at about the time that the English themselves were also becoming sufficiently literate and affluent enough to grant their consent to a British government gradually, but increasingly, beholden to a voting populace. A police force without a constitutional government as its foundation is despotic because there are no limits to its powers. Abuse ensues, and civil society breaks down.

The authors make clear, however, that the existence of civil police does not exclude the authorization of force. When civil police resort to force it is because of what the law requires for its enforcement, or because those on the receiving end are criminals. So it is that police—hopefully “civil,” but that depends on what we believe constitutes a constitutional government ruled by the consent of the governed—instigate a feedback loop in which the possibility of their coercion is judged against communities on the receiving end, who then exact their judgment of police actions the next time they enter the voting booth. Laws are deemed unjust or reaffirmed as just, and the cycle begins again.

Much of this is familiar to us from the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in the summer of 2014, all the way up to the shooting deaths of Renée Good and Alex Pretti in Minneapolis early this year. The essay itself, accompanied by a news photograph of 1968 riots at the Chicago Democratic National Convention, shows that these issues have persisted for decades since London of 1829, almost 50 years after the Gordon Riots unleashed the phenomenon of urban social unrest.

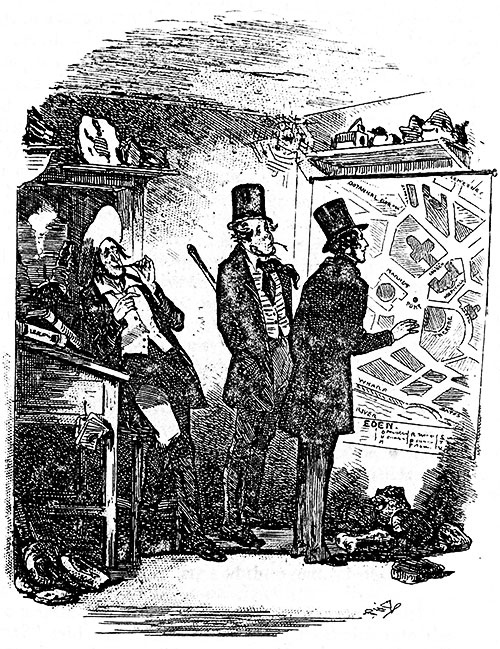

The Great Ideas Today essay makes detours into the fascinating debate that followed when Sir Robert Peel (1788 – 1850) first proposed the 1822 Metropolitan Police Act establishing the Metropolitan Police in 1829. Prior to the establishment of a constabulary, most English felt that the threat of punishment, not the coercive force of police intervention, was sufficient to uphold the law. The essay also notes that, before legal reform in England, it was legal to hang a child for theft of a handkerchief. Part of the problem then, too, was that the aldermen, magistrates, and watchmen already charged with enforcing the law and court orders were so corrupt that people shirked at giving them more power.

The punishment of crime, then, was seen as entirely different from its prevention. And the state itself was already deemed regrettably corrupt. The essay takes something of a drastic shortcut to explain how the English let go of these attitudes to form a respectable civil police force, but it offers an explanation all the same. Peel and his fellow advocates for civil police sought, as much as was possible, to recruit and train officers modeled on the civil behavior they were charged to protect.

“In philosophical terms it was a way of making him [the constable] the embodiment of the law, its personification. He would serve by his conduct to inspire the kind of obedience that for so long has been recognized as an expansion of civic virtue,” the essay states. “What the Metropolitan Police Act achieved was the reconciliation of coercion with consent, and not until this had been done could the problem of a civil police force be solved. Not until then was it seen that the only acceptable relationship between coercion and consent in a free society is essentially a didactic one with the law as teacher visible in a police presence inculcative of obedient habits.”

Readers would be well within their rights to complain that the authors could have instead made the point that, for civil police to exist, virtuous police officers must also be recruited and retained. But it is the implications of such a conclusion that matter as much as the conclusion itself. People, both police officers and civilians, are by varying proportions as fallible as they are virtuous. The “didactic” quality the essay references evolves every time the push and pull between coercion and consent is set into motion between police and citizens. The terms of the struggle are renegotiated every time a law is deemed unjust by civil disobedience, and the tension ratchets up every time we are forced to acknowledge that laws without the threat of possible force are no laws at all. The law may fix the line between coercion and consent, but in a democratic republic we at least have the prospect of that line moving forward or back.

Intriguingly, even in the distant year of 1983, the editorial board of Encyclopedia Britannica ends with a prescient, chilling paragraph warning that the western world’s run of good luck in maintaining civil police might have already run out:

“We may not soon again enjoy the possibility of a return to the social behavior that prevailed in at least some parts of the world for the better part of the past two centuries, when coercion had little overt part to play save as demonstrated by routine criminality and ordinary public disorders. If we do not have that possibility, neither will there be any chance of a truly civil police. We must expect instead coercive enforcement that in many respects is paramilitary and that has more faith in manipulation and technology than in an open presence and civil exchange. There were characteristic police traits in free societies throughout the world for what may have been only an historical moment.”

Our nation’s current ICE age may not endure for much longer. But as this 43-year-old essay makes clear, coercion without consent lasted centuries longer than the idea of civil police. We could be in for a long ride.