What the Acid Queen Can Teach Us

December 23, 2025

The old puzzle: Why do intelligent people so often make such disastrous choices?

“She lost herself, and she made ridiculous decisions,” writes WashU alum Susannah Cahalan in The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary. Eager for adventure, young Rosemary—future wife of Timothy Leary—reminds me of myself and so many other young women I knew, so full of curiosity and desire that we shush common sense.

She was born Rose Marie Woodruff, in stodgy St. Louis, on April 26, 1935. She later joined her first and middle name, placing “two fragrant herbs side by side,” Cahalan writes. “Such a small shift—visible but almost inaudible—that signals her lifelong dedication to the art of reinvention.”

At age eight, she had a mystical experience that filled her with a bliss she would spend the rest of her life trying to recapture. Reality never again felt like enough. And with her father a magician and her mother an amateur cryptologist, a fascination with the hidden or esoteric came naturally.

Smart but impatient, Rosemary left high school at sixteen. Swooning over an air force pilot seven years older, she got pregnant, and they married. He did not even wait until their honeymoon was over to let the temper he had hidden explode. “Beaten when I answered back, swore, or got angry,” she wrote. When she miscarried, she added a stark sentence: “His lower blows unmade the baby.”

Those blows unmade the marriage, too. Rosemary found herself a divorcée at age eighteen. Bored by St. Louis, she took the train to Manhattan, determined to have some fun. The woman had spirit: when a photographer told her she could model for him if she lost ten pounds, she marched off to a deli and ordered a Reuben stacked high with corned beef. She did win a few modeling gigs without starving, but they were not enough to keep her solvent. So she took “the second sexiest legal job available to her” and became a flight attendant. Then she fell in love with a Jewish jazz accordionist from the Netherlands who had lost many family members to the Holocaust and suffered night terrors. He styled himself tough, angry, and fearless; “Miles Davis loved him because he did not suffer fools,” Cahalan notes. But he had no patience for marriage, either. He was cruel and unfaithful to Rosemary, and when he was not teaching her to get high, he “treated her like shit,” a friend said later. That marriage, too, ended within a year.

Again and again, she drew men to her who then deceived her or treated her cruelly. Was she self-destructive, even masochistic? Or just too trusting, and then too sure she could change them? Young and female in the 1950s, with no family money to cushion her and no agenda of her own, she found herself twice divorced at twenty-one. There went her chance of a sweet bungalow in the new suburbs, its white picket fence covered with climbing roses, children shrieking with joy in the back yard.

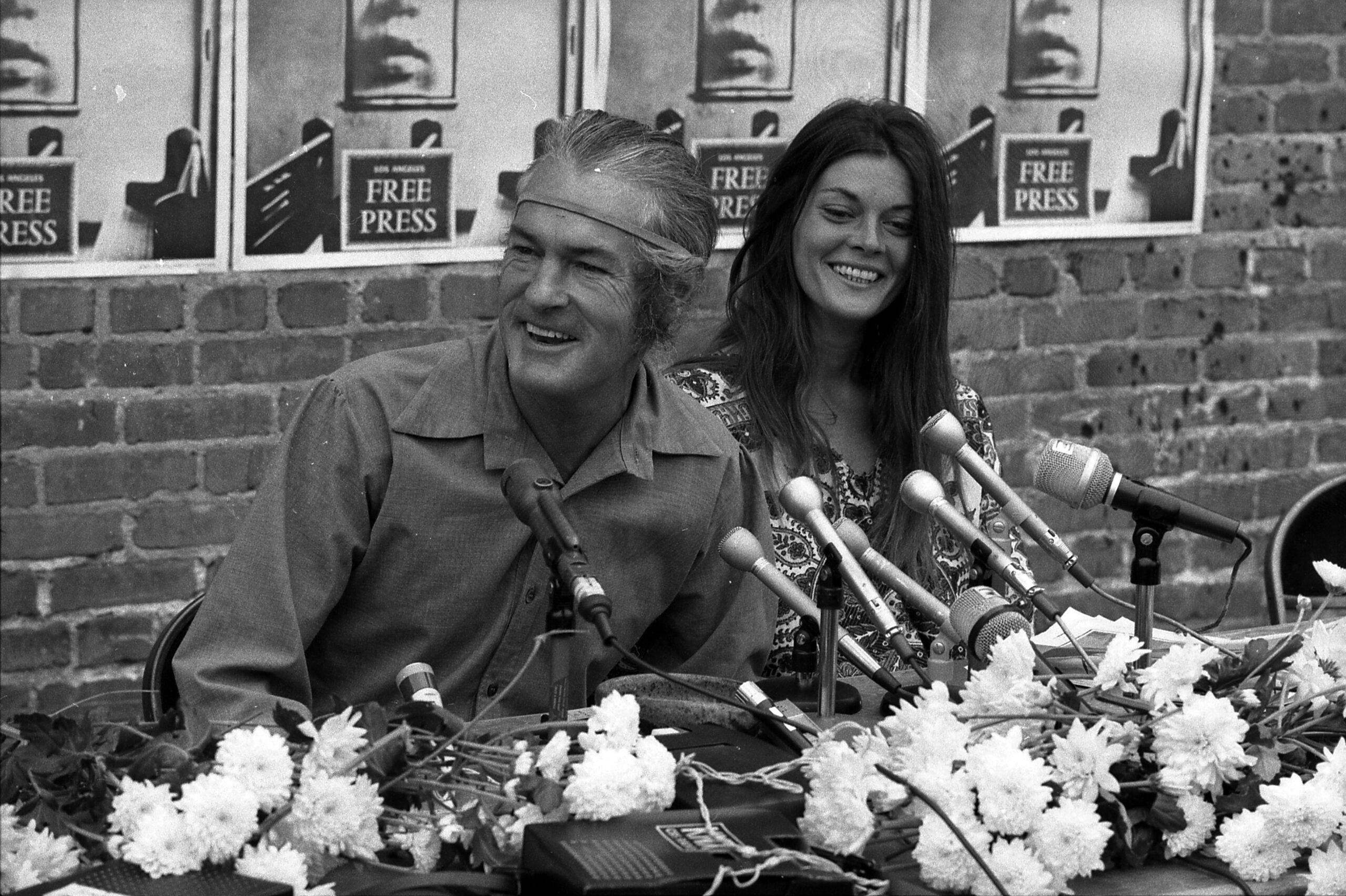

Instead—after a brief interlude with a lover obsessed with Chief Crazy Horse—Rosemary spotted her next husband, a thirtysomething rogue professor named Timothy Leary whose research subject was LSD. Intrigued, she showed up for a weekend at Millbrook, an acid commune, wearing tight bell-bottom jeans and the same sort of high-top sneakers he was famous for wearing in his Harvard classroom. A heavily underlined book by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was carefully arranged in her bag, just enough showing that Leary would recognize the author.

He later joked that he figured she had to be an undercover narc; “the Feds had nailed his taste in women.”

Years later, after the two married, she recalled him as “the first draft of pure oxygen after a trip to the dentist’s chair.” Alas, anesthesia wears off. And Leary, the counterculture’s beloved prophet, caused her plenty of pain.

“He was a trickster character,” Cahalan says, “very hard to pin down. Which was fun to write, but exasperating,” and would not wear well in marriage. In the book, she describes how he “traveled to Mexico and found God, the devil, and all of cellular history after eating seven musty magic mushrooms.” Also, how Rosemary kept him, by his own admission, “out of the trap of YMCA Hinduism, the goal of which was to become a Holy Man, a prospect she found too amusing for words.”

With Leary, Rosemary had the exciting, intense, transcendent life she craved. But once more, she had drawn a man who would at times treat her so terribly, it seemed as though he was bent on destroying her.

“She picked really badly,” says Cahalan, sympathy in her voice. “She was an unusual, weird person,” drawn to men who disdained normalcy—and who took that as permission to disdain kindness and respect.

I understand reaching to the far edge of polite society, because the guys closer in all sound the same. I remember the frisson of moving through the world with a cocky, irreverent, even arrogant guy. But time, instinct, and my mother’s tireless advice kept saving me. And by the time I hit thirty, sanity and stability had acquired a powerful appeal of their own.

I lived three decades later than Rosemary, though, and that, too, saved me—and nearly all my friends—from marital disasters. She had to marry. And the pressure to conform in the 1950s was so overwhelming, someone of her temperament was bound to have an equal and opposite reaction.

In time, she leveled. She traced her own separate outline, and she learned to keep her feet on the ground, Cahalan says, even when her head nudged the clouds. Researching the book, Cahalan worked her way into Rosemary’s mind by exploring what she explored. As she sifted through all those ethereal, esoteric practices, she found some wisdom there, and she felt herself loosening and opening. “I think I have my feet pretty well on the ground,” she says now, “but I added a bit more of the clouds to my own life. I’m still into tarot cards. I still throw the I Ching. I’ve taken herbalism courses.”

Rosemary Woodruff Leary spent her life looking for truths too wild to be captured in a textbook. She was Leary’s partner and assistant, throwing herself into his mystical scrutiny of psychedelics because she had no competing career of her own. She preserved the archives of his career and guarded his legacy. She gave physical form to his emphasis on “set and setting,” even sewing the clothes people should wear on an acid trip. “She offers a different relationship with psychedelics than the one that was championed at the time—and continues to be championed,” Cahalan tells me. “Her relationship was more cautious and circumspect. She felt that not everyone should take them, and that there was a shadow side to them.” When the surfers, self-styled mystics, and college kids of California were chanting her husband’s invitation to “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” hers was “a softer, quieter, less marketable approach.” And she stood by her beliefs, and by her friends, helping Leary escape prison and then spending a quarter-century underground (living at poverty level) to avoid arrest and to avoid betraying anyone else. She left Leary, and she learned to smile wryly at his professed need of her. But rather than harden into bitterness, she stayed open, kept searching for the truths of the universe. And when her heart failed her at age sixty-six, her last words were, “I understand now.”

Cahalan’s first book told the terrifying story of a month of psychosis when she, as a young journalist, was misdiagnosed with mental illness. (She had a rare form of viral meningitis, and if that one doctor in a sea of doctors had not finally reached the correct diagnosis, she could easily have spent years institutionalized.) That book, Brain on Fire, reached the New York Times best-seller list fast. Well, she had a compelling topic, you think—but her second book was just as well written and even more exhaustively researched. This third book—a smart history of psychedelics, relationships, and the sixties, complete with celebrity cameos—is so engaging, it manages to impart all sorts of information without you even noticing.

Acid Queen is a slice of zeitgeist, delicious and substantial. It is also a cautionary tale for young women—for anybody young—about the need to slow your impulses, ease into ice-cold adult life one safe toe at a time. The advice is thrust upon the young so often, it becomes a background hum, easy to ignore. “Before you get entangled with somebody else,” say the wise, “you must be in full possession of your own self, your own life, your own ambition.”

All those cocky young men had their ambitions. As she fell in love with each one, Rosemary Woodruff handed her own sense of possibility to them. Doing so might have seemed easier at the time, even inevitable. But she had to work hard to win back her life.