What if C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien Had Never Met?

October 29, 2024

Climbing to the fourth floor of Saint Louis University’s Verhaegen Hall, we dragged chairs into a tight circle in Belden Lane’s dusty, book-lined office and unpacked wine, cheese, crackers, apples. Then we spent an hour or two talking about what we were writing, wanting to write, thinking about, wondering. Three men, two women, some of us teaching and all of us learning, all of us in love with words. In rueful honor of our famous predecessors, we called ourselves the Stinklings.

In John Hendrix’s new graphic novel, The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, we watch the most famous members of the original Inklings meet in 1926 at Oxford.

“Jack Lewis, fellow at Magdalen,” C.S. introduces himself. “Tolkien, at Pembroke,” J.R.R. replies. Both men are drawn in tweed jackets, puffing pipes. Both are harrowed by their service in World War I—Lewis carries shrapnel near his heart, and Tolkien suffers a chronic infection infused by lice in the trenches. Both lost parents to illness when they were boys and were packed off to oft-brutal boarding schools, where they escaped into worlds of the imagination. Now, they are discovering that they share a love of Norse mythology. “It brings me more joy than I’m allowed to admit at Oxford,” Tolkien confides.

Soon they will join other writers and thinkers at the Eagle and Child, fondly dubbed the Bird and Baby, to drink ale and tea, toss out ideas either profound or nonsensical, and laugh. Later in the week, the Inklings will gather in Lewis’s rooms for serious readings and critiques. This convivial group will meet weekly for sixteen glorious years. The results will, no exaggeration, change the world.

Our Stinklings changed very little, by comparison. Belden would have written his beautiful books even if somebody locked him in solitary in Siberia; Pat would have practiced, written, and taught about nonviolence; Janice would have kept history amusing and profound for her students. But the fellowship emboldened each of us. And just having been part of a group whose members I so respected was a thrill that never faded.

“Nothing, I suspect, is more astonishing in any man’s life,” wrote Lewis, “than the discovery that there do exist people very very like himself.”

*

A New York Times bestselling author and illustrator, John Hendrix is the Kenneth E. Hudson Professor of Art and founding chair of the new MFA in illustration and visual culture at WashU. He was recently named the 2024 Distinguished Educator in the Arts by the Society of Illustrators, and coupled with his previous work of art—The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler—this profoundly delightful novel proves them right.

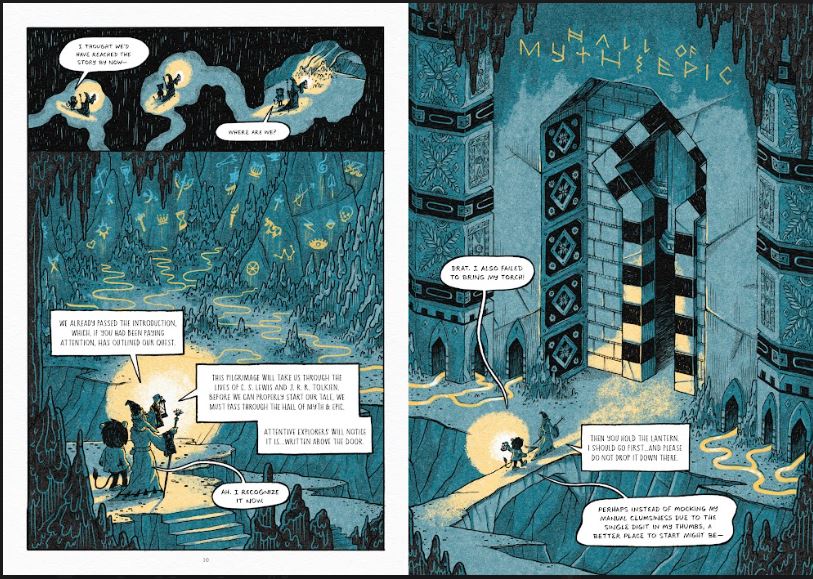

It opens on a snowy night in front of the fireplace. A Tolkienish wizard is telling Lewis’s beloved lion that “a myth points, for each reader, to the realm he lives in most. It is a master key. Use it on what door you like.” With light, witty commentary, these two lead us through the history of myth, rousing an angry minotaur along the way. Later, Professor Thistle (modeled on Dorothy Sayers) will sweep through literature distinguishing myths, epics, legends, and fairy tales.

These are side journeys, though. The main story springs from what Hendrix (whose faith was deepened by Lewis, and who carried The Hobbit around with him like a bible when he was a kid) always found magically coincidental. How wild, that these two men, shapers of the modern fantasy tradition, happened to be close friends.

Both Lewis and Tolkien fought, hard, in World War I. Both returned grieving good friends and the loss of innocence and illusions. Both feel a need to re-enchant the world. Tolkien has already begun: he sketched what would become his Middle Kingdom in the trenches and during his slow, bed-bound recovery. Now, for meaning and solace, both men move toward fairy tales (not the usual Oxonian work product) and give each other fierce courage as well as encouragement. When Tolkien shares one of his manuscripts, Lewis pronounces it a pure delight—then hands back a fourteen-page analysis for revisions.

“Each man deeply needed the other,” Hendrix writes, “though they did not realize it yet.” Lewis is the creative confidant who will accompany Tolkien on his quest and return him safely home. Tolkien is the friend who can help Lewis find “a myth that could join his heart and his mind,” reconcile his vivid imagination and stoic rationalism. “Nearly all that I loved I believed to be imaginary,” he will later recall. “Nearly all that I believed to be real I thought grim and meaningless.”

The friends argue easily and often about faith, Tolkien a staunch Catholic and Lewis first disillusioned then dragged back to belief almost against his will. But in the end, Lewis’s late-in-life, joyous marriage to a divorced woman—and his failure to tell his old friend, for fear of certain disapproval—will cause a rift in their long and glorious friendship. Hendrix manages to heal it for us, not with sentimental lies but with a redemption both could welcome.

Along with faith, joy is a theme in Lewis’s life. It comes to him in spurts that he initially dismisses as aesthetic experiences but later recognizes as love—divine first, and then, at long last, human. His theology and world-building are too sloppy for Tolkien’s taste: Jack (as C.S. is known) moves swiftly to capture his insights, while Tollers (Jack’s nickname for J.R.R.) takes slow linguistic pains. But both men are building worlds, making myths that some will welcome as escape and others will recognize as truth.

Scarred by childhood sorrow and war’s brutality, they watch the modern age begin. Steam-hissing machines replace manual labor and promise a future of refined artistic pursuits and leisure. This, Lewis dryly labels “the myth of progress.”

Today, we are caught in its latest revision.

*

With his moody color washes, expressive typography, and solid text blocks, Hendrix is making a myth of his own—beautiful, soulful, and brightened by quirky details. We learn that, though both men seem quintessentially English, Tolkien was born in South Africa and Lewis on the outskirts of Belfast. The friendship at first seemed unlikely: Lewis’s diary entry after meeting Tolkien described him as “a smooth, pale, fluent little chap…no harm in him, only needs a smack or so.” Tolkien dressed with a flourish, you see, and Lewis despised affectation. But soon, at least on every New Year’s Eve, they were dressed identically: in sheepskins that turned them into polar bears.

For all its amusement and edification, this is more than biography. It is a deep, almost allegorical tale of intellectual friendship. A few pinches of jealousy, an ideological clash, but mainly, a friendship so reciprocal, it steadied these brilliant men for years, kicking away writer’s blocks and shoring up resolve. The overlap of their lives was not, as young John Hendrix thought, a magical coincidence. Though romantics talk of garrets, real creativity is always, in one form or another, collaborative. Anyone who boasts of originality owes a thousand debts.

Besides, as Tolkien reminds us, “Someone else always has to carry on the story.”

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.