(Criterion Collection)

Released five years after the surrender of imperial Japan in World War Two, but at least two decades before Americans would start loathing Japan’s prowess in mass-producing fuel-efficient compact cars, Rashomon had the immediate disadvantage of provoking xenophobic reactions.

Even in the early nineties, as a college student attempting to bond with elders, various relatives walked out of the living room and out onto the porch when I suggested we watch it. So it was all the more interesting to learn, upon investigating the Wikipedia page for director Akira Kurosawa’s most famous film, that no less than Ed Sullivan praised it to high heavens when it premiered in 1950. There is symmetry in the fact that the person most responsible for introducing Americans to the Beatles would also not just endorse, but recommend heartily, Kurosawa.

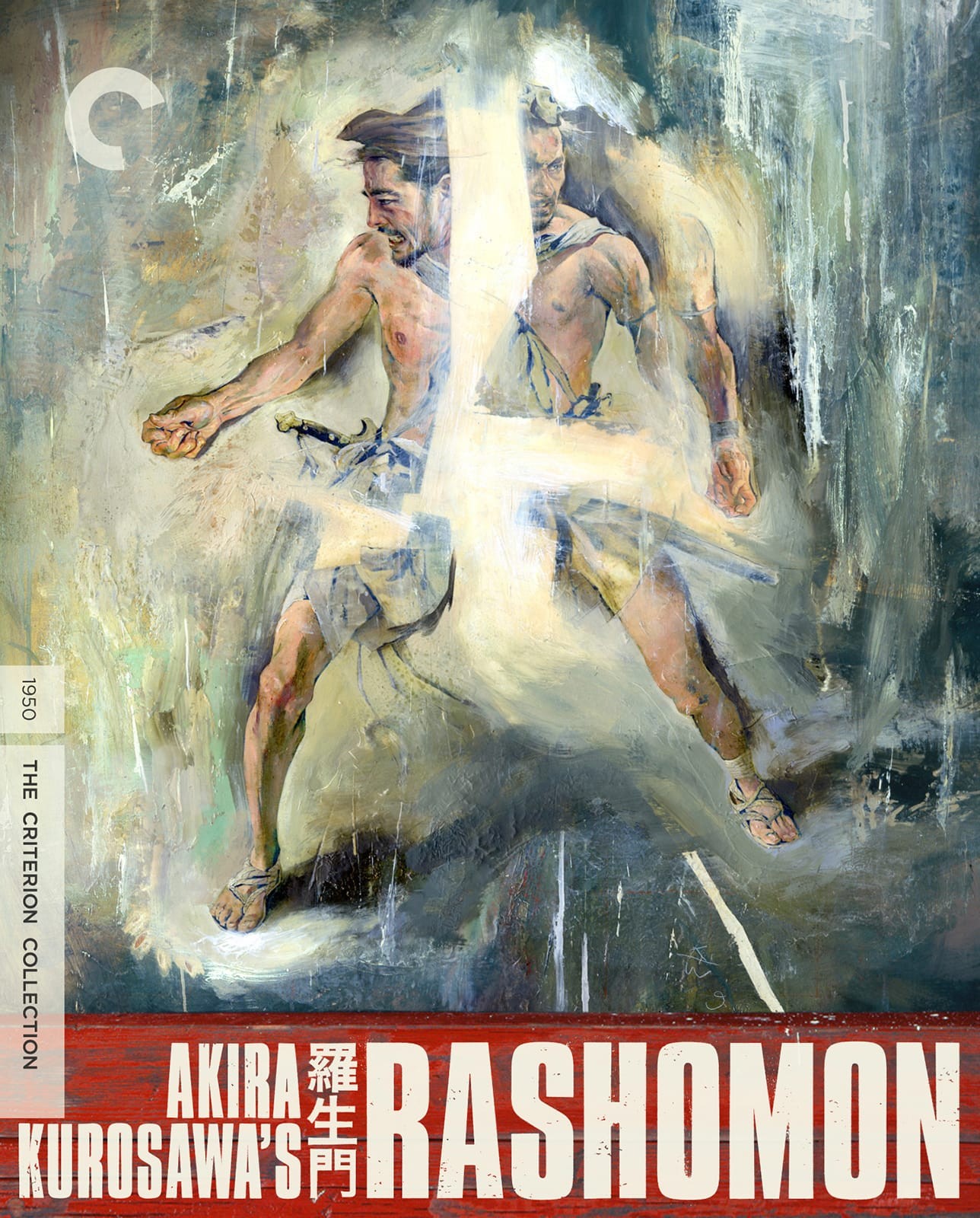

The rest is not mere history, but an all-encompassing reference point that has since seeped into almost every corner of culture and society, and lodged there ever since. In portraying four versions of what should be, but are manifestly not, the same story, a woodcutter, a thief, a noble lady, and the ghost of her allegedly murdered husband all have their say in front of an unseen magistrate. All four describe contradictory, competing events of what transpired. Kurosawa’s cinematographer, the celebrated Kazuo Miyagawa, has a field day constructing visual metaphors around truth’s slippery nature. The dappled light of the Japanese forest throws rapid-moving shadows as each character walks into each progressing scenario. The thief, played by Toshiro Mifune, and noble lady take turns staring at the sun or clouds. Those too, are metaphors on the blinding or hidden nature of truth.

By the film’s end, as art cinema hipsters might have said after finishing their espressos, “everything is true but nothing is true.” Saving the film from its own inherent pessimism, though, is the woodcutter. Joined at the film’s beginning and ending by a Shinto priest and a pauper under a dilapidated city gate—named after the film itself—the three argue about which version of the story is true until the cry of an abandoned baby interrupts them. The pauper steals the infant’s blanket, while the woodcutter decides to adopt the infant despite already having a large number of children for his own to care for. Hope for the future, and the impulse to believe in a future despite others’ failures to live in truth, save the day. For some high-brow film critics, the quickest way to brandish your refined taste bona fides is to complain, in no uncertain terms, that while most of Rashomon is brilliant, the ending is unforgivably maudlin.

Like whispering “Rosebud,” everyone knows what invoking Rashomon means or, given its legacy of arguing truth based in vanity and faulty human perception, should mean. From legal citations to experiments with non-linear storytelling and on into to contentious autopsies of marriages and work relationships gone wrong, the film made its mark on ballet, on popular films like Gone Girl, and even on The Simpsons.

The first admission any fan of this film must make is that, while Kurosawa accomplishes something wholly original in film, there is nothing altogether new about competing narratives and stories. Anyone raised in Christianity is struck by the myriad differences in all four books of the New Testament Gospel, to say nothing of all the letters to the early church in which Paul and others attempt to teach from events they never witnessed first-hand. Even before the New Testament, King Solomon cut straight to the point when trying to determine which mother an infant belonged to. Truth, like love, can be worth the risk of death.

Even in film, characters weighing the instability of truth, or at least human motivations, is nothing new. Federico Fellini said, in 8+1⁄2 (1963), “Happiness is being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” Jean Renoir, as Octave in The Rules of the Game (1939), knew that if life was not an endless series of competing truths, it was still an unmanageable story of competing actions: “There is one thing, do you see, that is terrifying in this world, and that is that every man has his reasons.”

Watching Rashomon for the first time in years, and then dipping my hand in the endless trove of online commentaries, I was struck by one interpretation that saw the film as a murder mystery to solve, rather than an unsolvable riddle to which we capitulate. Decades ago, before our hyper-partisan age of conspiracy theories stewed in social media, the so-called “relativity of truth” was scorned by the middle class as a hippie’s playground of moral morass and ethical confusion. Running up the flag of “context” in determining right from wrong, and even entertaining different truths, was seen as a weakness. Now, in the face of “fake news” and strategic, state-sponsored disinformation, the aisles have shifted and been rearranged. Yet the empirical evidence of science, the white papers of long-funded institutions, and elites with graduate degrees are not narrative sources for us to throw up our hands in front of, but tangible and consequential sources of information that must be defended, or at least seriously entertained.

At one entry point, Rashomon is a film about losing trust when verifiable truth cannot be found. Its sentimental (to some) message is that we must find ways to move forward with life even when trust between people in society vanishes. True enough. But the flip side of Kurosawa’s great film, revealing a murder mystery to solve, is also a world in which the search for truth, however difficult or naïve, must never be abandoned.