Time to Revise the Golden Rule

February 18, 2025

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. A simple idea, the core of Christianity and every other world religion. I remember parroting it as a kid. Later I realized it instilled equity—all human persons have the same value, and no one should be treated as somehow less than you. It also waved a white flag, distracting people from spite and vengeance. And it laid a foundation for the sort of commonwealth sharing that today is vilified as socialism.

The first known use of the Golden Rule is in “The Eloquent Peasant,” a story told in the shadows of ancient Egypt’s pryamids around 1850 BCE. “Do the doer to cause that he do,” the tale commands, its maxim of reciprocity inspired by the goddess Ma’at’s emphasis on harmony and balance.

A negative corollary pops up centuries later: “That which you hate to be done to you, do not do to another.” Humans seem to learn better with fear and warning. Whatever the formulation, though, the Golden Rule swiftly achieves a remarkable universality. It appears, inked in Sanskrit, in India’s Mahabharata epic. “Do not do to others what you know has hurt yourself,” the Tamil Book of Virtue of the Tirukkural notes. Thales, Socrates, Plato, and Epicurus each take a spin, followed by Seneca in ancient Rome. The Zoroastrians say, “That nature alone is good which refrains from doing to another whatsoever is not good for itself.” Hindus say, “One should never do that to another which one regards as injurious to one’s own self.” The Buddha urges, “Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.” Hillel the Elder boils it down: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow: this is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and learn.”

On and on goes the list. A poster showing thirteen faiths’ versions of the Golden Rule hangs on permanent display at the United Nations. Jesus makes his version of the Golden Rule the second great commandment, and Mohammed tucks its message into Islam, breaking a preoccupation with tribal survival and blood vengeance by saying gently, “As you would have people do to you, do to them.” Asked for one word that could guide a person through life, Confucius supplies shu, reciprocity. Even Wiccans and Scientologists have versions of the Golden Rule, and Yoruba warns, “One who is going to take a pointed stick to pinch a baby bird should first try it on himself to feel how it hurts.”

All over the world, the injunction has remained essentially the same, intact for millennia. Granted, it has often been applied selectively—only to other men, for example, or only to one’s high born peers. Still, the Golden Rule shines on, proof that we have always recognized our need to fight ethnocentrism and egotism.

But here is a sentence I never thought I would utter: Thank God for business and self-help gurus, with their relentless demands for self-improvement. In recent years, several authors have offered us a revision so obvious, you wonder how it escaped Confucius, the rabbis, and Jesus. The first official update in millennia, it is dubbed the Platinum Rule:

Treat others as they would like you to treat them!

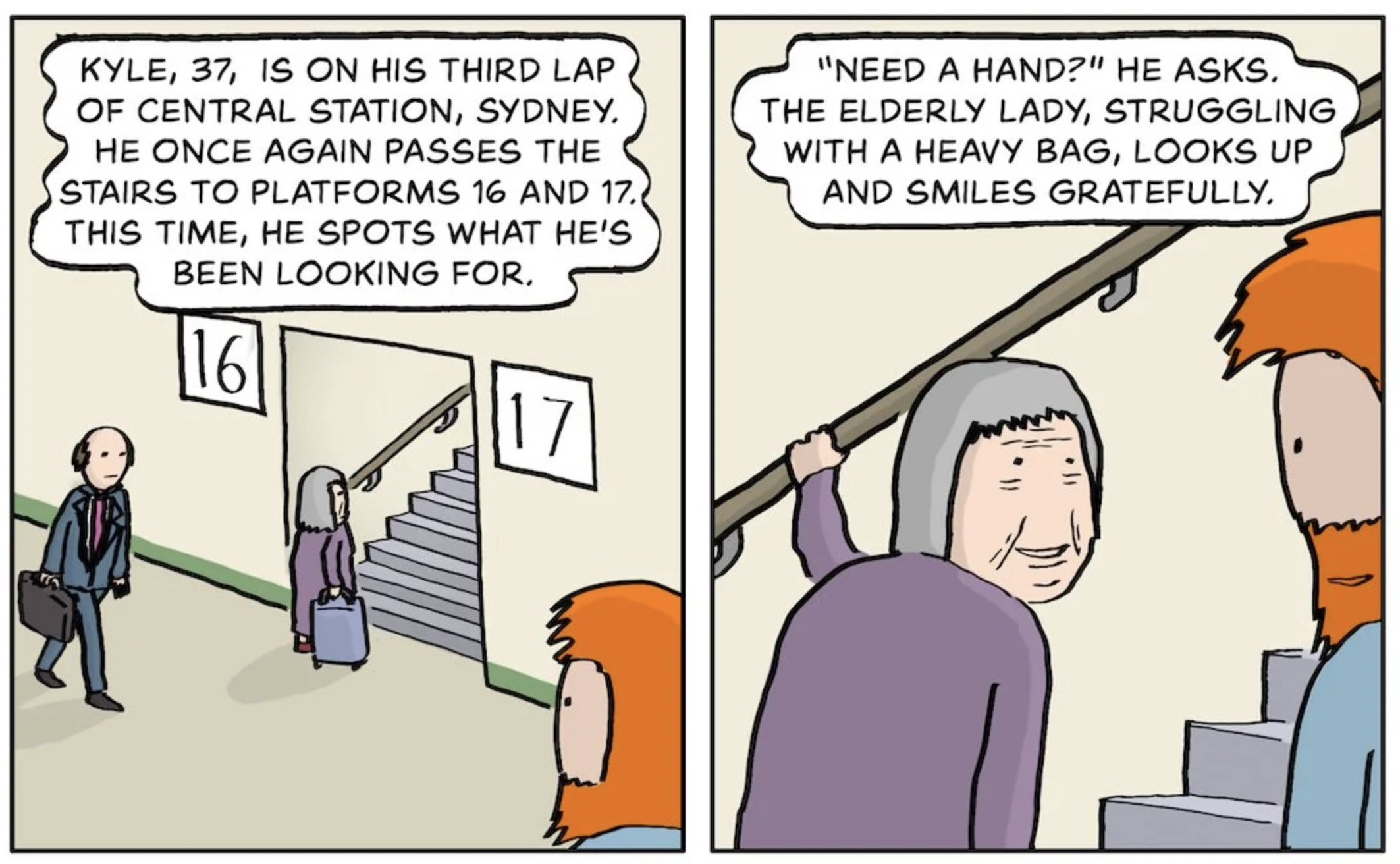

In other words, this is not about you. Figure out how the other person, who may have different cultural influences, needs, or emotional baggage, wants to be treated.

The shift reminds me of the “love languages,” a bit of relationship wisdom that went viral, then died off, probably because it felt a little too boxy. We all want to be loved in every way possible. But the Platinum Rule holds in every other arena, because when you set romantic demonstrations aside and deal with an everyday partnership, you have a far better chance of being heard if you learn to communicate in the way the other person prefers.

(You know you have broken through when you start buying them the presents they really want, rather than the kind you love to give. I once took great delight in buying my straightforward historian husband a flowing white linen poet’s shirt. I wound up wearing the thing myself. Now I fork over cash for comic books and long, boring history tomes I will never want to borrow.)

The Platinum Rule, then, is a definite improvement, fast adopted in medicine, social work, any cross-cultural work. Turns out the Golden version really only works in brief exchanges with strangers, because at that basic level, what we would want likely does coincide with what they want. It was a good starter for all those centuries, useful as a teaching tool because thinking of what we would want has automatic appeal. With Platinum, all our attention has to land on the other person. Maybe we are evolving?

I am curious what the next revision will be. They obviously take a while to show up, because human society expends far more time, money, and energy on warfare and acquisition than on ethics. But surely we can continue to improve, maybe learning to adjust our responses not only to the individual but to their situation at that moment?

Venturing inside someone else’s psyche requires strong observation and navigation skills, not blind obedience to some maxim. As George Bernard Shaw grumbled, “The Golden Rule is that there are no golden rules.” He went on to quip—foreshadowing the Platinum Rule without realizing it—“Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same.”

At last, we are catching on.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.