Time is the Book That Lets Us Endure Our Fate

December 11, 2024

Rory came over again from the old place. His wife had been gone three weeks this time, and he would drive to the airport to get her after we ate pork nachos. We have known each other for twenty-five years.

To kill time, we talked about writing for a platform on the regular. I told him that the day before I had spent part of my wild and precious life trying to arrange words about corporations’ pointless “gifts” to customers. It was my choice, I said, but what am I, “Architecting the Future While Relentlessly Delivering Today’s Business Growth”?

We agreed time was always limited but when you got to a certain age and your friends were no longer all well and maybe you were not feeling so great yourself you realized how many words you had already said in a life. If they were definitive, job done. If not, why keep trying? We do anyway, with the pages we have left. The Trappist tradition of speaking only when necessary is noble, yet Thomas Merton wrote fifty books.

If you had a blog to fill, what would you put in it now? I asked Rory.

We pondered themes.

“responsible commentator”

“to instruct and to delight”

“catch the glimmerings of a metaphysical beyond”

“Grecian grandeur with the rude / Wasting of old time”

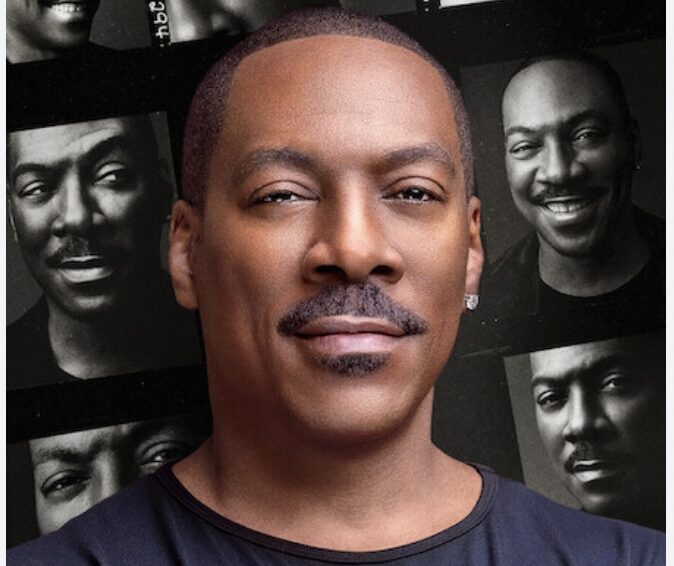

Rory is a poet who has a novel manuscript that a Hollywood screenwriter offered to help get published. (Take your pick: literary agent or entertainment agent? she says.) He said if he had a blog like a hungry hippo he would write serially about how books by others—Emerson, Whitman, Borges—appear in his own work, and why some of the mentions in his manuscript are merely in-jokes with his second-most literary friend but also serve structure and meaning in a story that could be as meandering as ones by Knausgård, JA Baker, Sebald. Books are part of our experience of life too.

I said for me classical Asian poets might be a blogger’s model. Su Tung-p’o shows us an ordinary fine spring day, strollers drinking in the inns, children scampering, both crows and kites set in flight, and there is “that fellow who has gathered a crowd [and] says he is a Taoist monk,” in the Rexroth translation. The guy sells lucky charms to ensure that silk cocoons and sheep grow enormous. “Nobody really believes him. / It is the spirit of spring in him they are buying,” Su says. Later he will use their money for wine and be lying face in the mud.

“How many Spring Festivals are we born to see?” the last line of Rexroth’s final Su Tung-p’o poem says. It is so simple; it is all there. The writing has lasted a thousand years.

If only I could do that the rest of my time! But I will find something. Wendell Berry: “It may be that when we no longer know what to do / we have come to our real work….”

I told Rory my need for a sufficient idea woke me at four am the night before, and I had muttered something into my recorder. Let’s listen to this, I said, might be embarrassing.

My voice was halting and sleepy. “Time is there to stretch out the physical and emotional experiences of our fate,” I said. “I dreamt of the army and all the banging around in trucks.”

I told Rory I thought I had meant that if long events, such as moving around uncomfortably for four years in trucks, helicopters, boats, and on foot, took place in an instant, we would never survive the first of them. Getting born was bad enough, and that usually took only a day.

He liked the idea, and we considered other experiences in this light, which is to say almost all of them: childbirth, intimate relationships, earning a degree, getting a tattoo. If you had all the orgasms of your life in a millisecond, you would vaporize in a spurt of moist steam. At least death comes mercifully quickly for some.

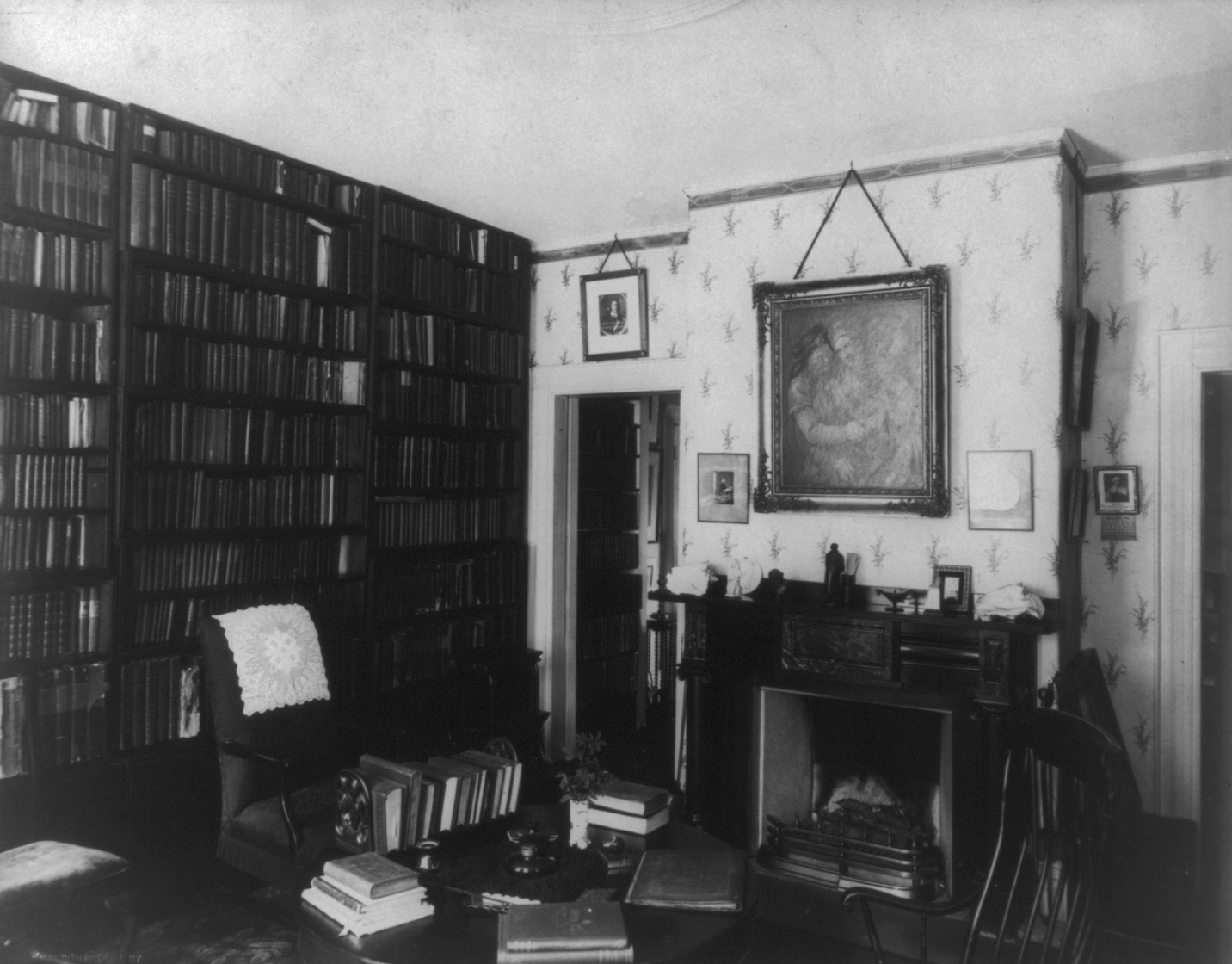

In his journal W, from 1845, Ralph Waldo Emerson says that we read “the great humane Plato…impatiently, still wishing the chapter or the dialogue at its close.” But if we wish only to be done with the temporal work of reading the book and to have absorbed it, “The reader in Plato is soon satisfied that to read is the least part. The whole world may read the Republic & be no wiser than before.”

As with our lives, we must savor the enduring, through time.

“When we say, It is a fine collection of fables or when we praise his style or his common sense or his logic or his arithmetic we speak as boys,” Emerson says. “The criticism is like our impatience of the length of miles when we are in a hurry.”

Rory headed for his Honda, and I called out that I would see him soon.