“This Is Personal. And No, We Are Not Criminals”

February 13, 2025

His is not an easy name to forget. Selam Deutschmann. There is a story behind it. His partner’s first name is Eritrea, which was her heritage but not yet a nation when she was born. There is a story there, too.

Selam Deutschmann is a chiropractor, Eritrea Habtemariam a nurse practitioner. They live in one of those big, welcoming old homes off Skinker, and when I show up, they are in the kitchen making a beef stew with onions, garlic, ginger, tomatoes, jalapenos, mitmita (hot ground peppers) and berbere (a blend of milder peppers and eight spices that Selam scoops out of a giant canister). Watching from a deep window seat is their Wheaton terrier, Al Pacino (whose name no doubt also holds a story, but feels so oddly right, I do not bother to ask).

I wanted to meet Selam because a friend told me that he came here as a refugee from the Ethiopian civil war, and that he was happy to take the name of the German couple that opened their home to him, his twin sister, and their little brother. Jarred by the recent political maneuvers, I desperately needed to hear a story that openhearted.

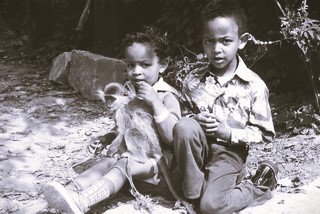

Eritrea continues the chopping and stirring while Selam joins Al Pacino on the window seat. As he speaks, the brick walls dissolve, and he is nine years old again, back in Addis Abbaba. “My mom took us on an airplane out of the country,” he tells me, and in the phrasing you can hear the wonder of that first plane ride. Selam, his twin sister, and their little brother were the youngest of twelve. The eldest boys had already left home on foot, heading for Sudan to avoid being conscripted into the army. The other kids would stay in Ethiopia with their father, who held an important job in banking. (The king had sent him abroad for schooling, and he had brought back insights from a New York bank to help start a national bank of Ethiopia.)

Selam’s mother first took her three youngest to Yemen for asylum. She had a job with the United Nations at the seat of the African Union, and she was waiting for a secretarial job to open at the UN headquarters in New York. When word came that the position was open, she took Selam and his sister and brother to a Christian boarding school for refugees, just for a year until she got situated.

The campus was in Iowa, “in the middle of a cornfield,” he groans. “A chicken farm to the left and a pig farm to the right. And the smell! Everybody walked around like it was normal.” Selam was a city kid; the farm chores took some adjusting. But there were almost thirty kids from Ethiopia at the school, which helped, and there were other kids “from North Korea, Sudan, anywhere there were issues.” He glances at Eritrea, whose head is down as she mixes ground chickpeas for shiro. “But she’s the one with the story.”

She laughs, protests a little, then trades places with him.

“I was five years old,” she begins. “My brother was three and a half. We were Eritrean, living in Ethiopia. We had to go across to Sudan. My father was already there, had been for several years, so I had no real memory of him. We had to leave secretly, because if anyone found out, they would assume we were following him, and they would want to know where he was.” Simply because he was Eritrean, he was suspect. “So we left in the middle of the day, casually, like we were going to the market. And we just kept walking.”

Little Eritrea muttered to herself, “I don’t want to go! I want to go back and play with my cousins!” Sensing resistance, her mom made the trip sound like an adventure. “We’re going to visit relatives,” she said, not even mentioning Eritrea’s father lest one of the children let it slip.

Part of the way, they rode camels, but the rest of the journey, they made by foot, walking as quietly as they could. They traveled at night and camped out during the day, trying to avoid the fighting. Helicopters zig-zagged overhead, so they could not risk a fire to cook. Selam, who has taken over the stew and shiro (a sort of chickpea gravy) and is starting a pan of wat (lamb stew), explains from the stove: “You have the smugglers, thieves, and bandits; you have militia, you have soldiers from who knows which side.”

“We’d lived a protected life—we had a nanny—and all that was taken away,” Eritrea says. When the blisters on her feet broke open and her empty stomach growled and her little brother fell and broke open his chin, their mother finally told them, “We are going home. Your father is waiting for us.”

That made it bearable. For a while. But the journey took more than six weeks. “Once the smugglers get you across the border, you go into these camps—the kind we see now in the Sudanese desert—and all these kids from different countries are there,” she says. “I remember my mom hanging on to both of us for dear life.”

Finally, the kids were reunited with their father. But in that sweet moment, Eritrea burst, “You’re not my dad!” Her uncle had taken care of her for so long, he was her father. Now this strange man was swiping away tears.

“Give them time,” her mother murmured.

The kids would go to school in Sudan—where they did not know the language and had no friends. They adjusted, adding Arabic to their native Tigrilya language, and six years later, they most definitely did not want to move again. Let alone to cold, bleak South Dakota, where they would have to learn yet another language.

“That was the worst time of my life,” Eritrea confides. “I went on a hunger strike! I said, ‘You have to send me back home!’ Instead, she did what she always did: made friends quickly. And when she reached adulthood, she fell in love with a man who had come from St. Louis to play in the Eritrean community’s annual soccer tournament.

They married, settled in St. Louis, and had three children. After ten years, the marriage broke apart. Still in St. Louis, Eritrea socialized with the Ethiopian and Eritrean community here—and four years after her divorce, she met this kindly Ethiopian chiropractor, a single father utterly dedicated to his daughter.

Parenting challenges drew them together, and they became good friends. Friends, they stressed repeatedly, until finally Selam’s daughter exclaimed in exasperation, “Why do you keep saying that? You know you’re more than that!” At which point they looked at each other, both thinking, “Okay then. Maybe we can try this.”

Eritrea grins. “Best decision ever.”

Selam is scooping kibbeh, a spiced clarified butter, from a big jar, but he looks up and gives her a look so tender, my breath stops. For a long time, he says, his emotions were frozen. Not even six months after his mom fetched them from the school, she was stricken with a headache so fierce, he remembers fetching her aspirin all evening.

The next morning, he found her dead.

A brain aneurysm was more than an eleven-year-old could understand. His father flew to New York but could not stay. He begged the Christian school in Iowa to take the kids back. But now they had no visa, no status. “It’s okay,” the head of school said. “We will just adopt them.”

The Deutschmanns both taught at the school, and Mr. Deutschmann was the pastor. Born in Germany, he had come to the U.S. when he was eleven. “After World War II,” Selam says. “So he saw a lot of stuff, too.”

Before leaving, Selam’s father told him, “Your name is going to change.” In Ethiopia, children take the first name of their father as their surname. Here, the adoption would make theirs Deutschmann. A name Selam could not even spell. “No,” he blurted. “Take me back with you, because we are not going to change anything!”

His father soothed him, saying it was “just a name.” And by the time Selam reached college age, he had a deeper sense of how the Deutschmanns had saved him, and he was proud to bear their name. Later, he could have changed it, but having his own child made him even more profoundly grateful for what they gave him.

“The Deutschmanns were not forceful, insisting, ‘You’re our son,’” he recalls. “Nothing aggressive. Just very welcoming and loving people. Every Christmas we had a real Christmas tree, with candles on it, and we’d sing Handel’s Messiah.” The Deutschmanns had a set of boy-girl twins just like Selam and his sister, and all the kids played together.

“I missed my dad, though,” he adds, the light leaving his face. “I used to write him every month—that kept me from forgetting our language. He came for our high school graduation in 1991, and he came in 2005 to visit me.” On his last night, he and Selam talked warmly. The next morning, Selam found his father dead. History, repeating itself.

Brightening, Selam lists all the books his father wrote, first on finance but then on the history of Ethiopia. Had he been able to stay home, Selam thinks he might have become a historian like his dad. “But he had to be careful, even in his books. Spies were everywhere—even if a little kid said something, another little kid might tell his father. And if you said anything against the government, you just disappeared. One of my dad’s good friends was a journalist, editor of the Addis Times, and he wrote a book saying, ‘This war has to stop. Make a truce.’ Then he disappeared.”

Selam places injera, a light, spongy flatbread, on a giant platter. Then he shifts gears, telling me about the time he dislocated his shoulder playing soccer with his buddies. The chiropractor took away the pain. When I grow up, I want to be like this guy, Selam vowed.

First he had to finish college. Like others at the boarding school, he enrolled at a Christian college, John Brown University, in Arkansas. His family was Coptic Christian, but this kind of Christianity was far stricter and more conservative, and the school was in the Ozarks, and he kept seeing KKK signs everywhere. “I just never felt welcome,” he says.

He transferred to Mizzou, then Logan Chiropractic College, working summers at his uncle Mengesha’s restaurant, Bar Italia, in St. Louis. After graduation, he planned to move to D.C. “But then I had a kid,” he says, his smile wide. “She was born in 2000, and everything changed. Everything became about her.”

And now, also about Eritrea and her kids. Which makes the Trump Administration tough to stomach.

“My heart just drops every time that man comes on TV,” Eritrea says. “At work I just have to keep quiet. I hear things like, ‘Oh, they need to close the border.’ Once I said, ‘You know, you are talking about me. We came to this country as immigrants.’ She said, ‘Oh, but not you.’” Eritrea looks up. “This is us. This is personal. And no, we are not criminals.”

I ask if their kids are scared. “We are more scared for them,” she says. “Our girls are fearless. They are ready to stand up for their rights and for other people’s rights.”

Selam’s face sets grim. “I do physicals for truck drivers,” he says, “and one told me that half the people didn’t show up at church this Sunday because they’re so afraid.”

Neither Selam nor Eritrea feels fully at home here—but they no longer feel fully at home in their native countries, either. So much has changed, so much has slid out of memory. When Eritrea took her kids back for a visit, though, her seven-year-old exclaimed, “Everybody is like me!” No one questioned who they were. “Here,” she says, “it’s oh, well, okay, you are American, but where are you from?” A benign curiosity that still distances—and could darken at any moment.

Selam thinks about those years after his mother died, how all the change and loss made him reluctant to feel at all. “To come to a new place and then lose her—it makes you—” he says “hardened” at the same time Eritrea supplies “resilient.” He smiles ruefully. “I think both.”

What anchors them, Eritrea says, is the work they do. “Being there at the worst time for someone, because you know what that feels like.” Taking away pain.

Would they ever consider leaving this country, I ask, given the turn it has taken. Privately, I am thinking of the file my husband and I have started, exploring expat opportunities….

But they are shaking their heads no. “We have made lives here,” Eritrea says. “We’re part of this community.” Giving, and healing, no matter what the government says.

“You are still guaranteed certain things here,” Selam says quietly, “as bad as it sometimes feels.”

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.