The Purpose of a Cookery Book

February 7, 2026

An English woman named Jessie Conrad published a book called A Handbook of Cookery for a Small House in February 1923. Like many old cookbooks, it contains recipes we all still know and enjoy, such as an apple tart from scratch, as well as those you might not have enjoyed in a generation or two, such as calf’s kidney on toast; bacon pudding; pigeons with carrots; and “Boiled Mutton for an Invalid.” Good sturdy cookbooks like this detail the old ways, yet have an openness—all protein is good protein in want—that might prove useful again.

Conrad’s writing is rarely saucy, but in a section called “The Treatment of Vegetables,” she writes, “Potatoes are to my mind one of the most ill-use vegetables we have. They require simple care to make them a useful and welcome addition to at least two meals in the day. […] It is indeed a fact that in the case of the poor potato, God sends the food, and the devil the cooks!”

She is also a woman of her time, as they say, and class. She offers instruction for “a small house,” but, “Cooking ought not to take too much of one’s time,” she says. “One hour and a half to two hours for lunch, and two and a half for dinner is sufficient, providing that the servant knows how to make up the fire in order to get the stove ready for use. Most girls will quickly learn to do that and how to put a joint [a large piece of meat, usually with the bone] properly in the oven.”

She also shares the Victorians’ obsession with odors. “The bane of life in a small house is the smell of cooking,” she says. “Very few are free from it. And yet it need not be endured at all. This evil yields to nothing more heroic than a simple but scrupulous care in all the processes in making food ready for consumption.” This is tragic, given that many of her recipes call for onions.

Meanwhile, her recipe for spaghetti says: “Put half a pound of spaghetti into boiling water with a good pinch of salt. […] Cook for one hour….”

But such cookbooks, in all their charm, surety, and prejudices, abound. The most remarkable thing about Jessie Conrad’s is that her husband, Joseph, wrote the preface.

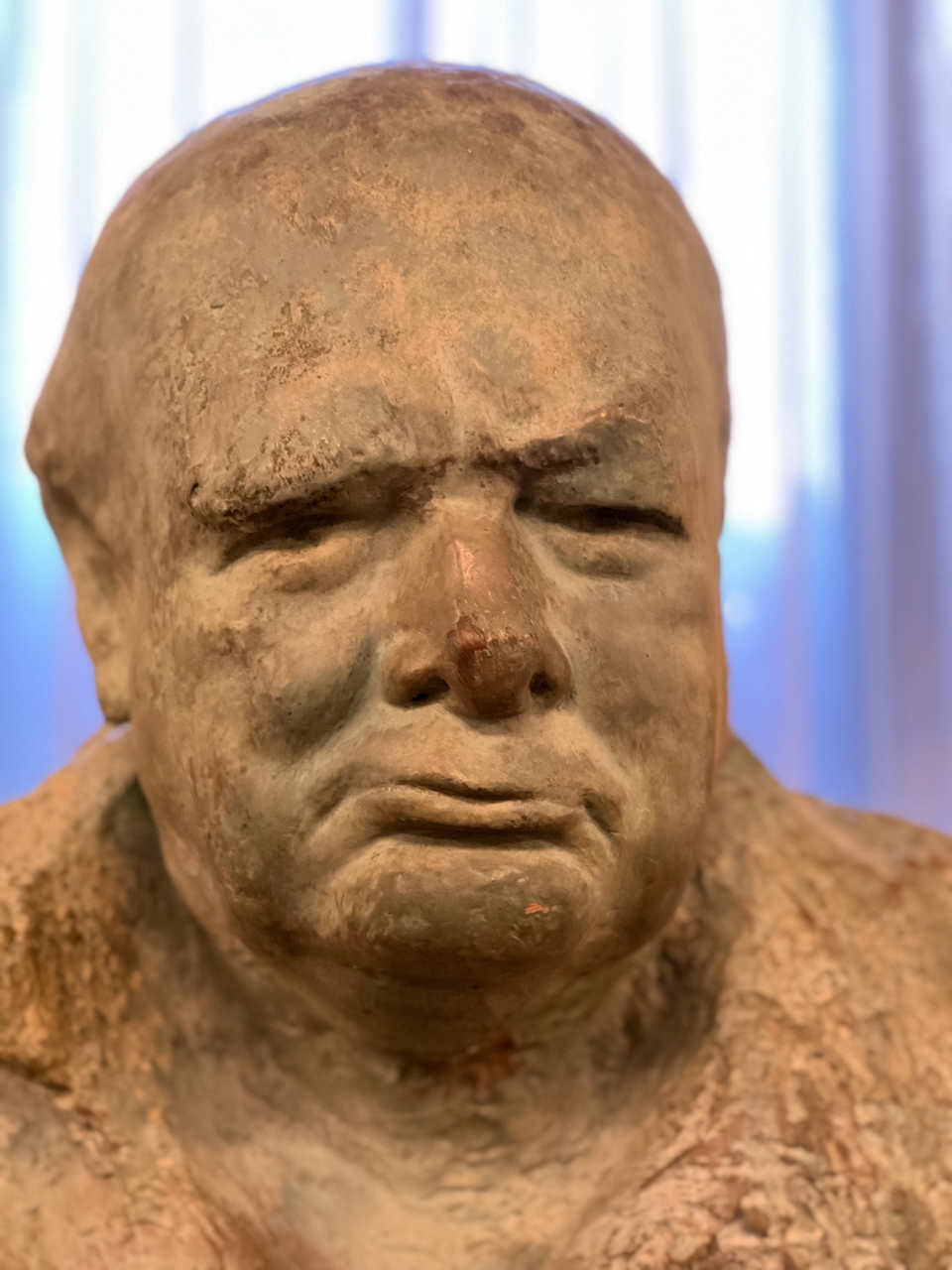

Joseph Conrad had been married to Jessie 27 years when A Handbook of Cookery for a Small House was published. His most enduring work—Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim, Nostromo—was 20 years old, but he was hugely popular and famous. He would die, at the age of 66, a year and a half later.

He is sweet enough about the task of writing the preface, even while determined not to be personally held to account. “Without making myself responsible for her teaching (I own that I find it impossible to read through a cookery book) I come forward modestly but gratefully as a Living Example of her practice. That practice I dare pronounce most successful. It has been for many priceless years adding to the sum of my daily happiness.”

Yet he cannot help being Conrad (say his name in an Orson Welles voice) and makes what may be the boldest statement in all of cookery books: “Of all the books produced since the most remote ages by human talents and industry those only that treat of cooking are, from a moral point of view, above suspicion. The intention of every other piece of prose may be discussed and even mistrusted; but the purpose of a cookery book is one and unmistakable. Its object can conceivably be no other than to increase the happiness of mankind.”

Then he promptly ruins his own thesis by indulging in this weird digression:

“A great authority upon North American Indians accounted for the sombre and excessive ferocity characteristic of these savages by the theory that as a race they suffered from perpetual indigestion. The Noble Red Man was a mighty hunter but his wives had not mastered the art of conscientious cookery. And the consequences were deplorable. The Seven Nations around the Great Lakes and the Horse-tribes of the Plains were but one vast prey to raging dyspepsia. The Noble Red Men were great warriors, great orators, great masters of outdoor pursuits; but the domestic life of their wigwams was clouded by the morose irritability which follows the consumption of ill-cooked food. The gluttony of their indigestible feasts was a direct incentive to counsels of unreasonable violence. Victims of gloomy imaginings, they lived in abject submission to the wiles of a multitude of fraudulent medicine men—quacks—who haunted their existence with vain promises and false nostrums from the cradle to the grave.”

He was a man of his time, as they say, and a huge fan of James Fenimore Cooper. As far as I know, Conrad never met a Native American. A Handbook of Cookery for a Small House published a few months before Joseph Conrad’s first, and only, trip to the United States, where he got nowhere near the Great Lakes or the Great Plains.

The New York Times of May 8, 1923, in an article titled, “Conrad For ‘Movies’ But Can’t Sell One,” reported his “civilized interview” at the Doubledays’ “large country house” in Oyster Bay, Long Island, with “a score or more of journalists from across the nation who, in the words of one witness, ‘bombarded him with questions about cooking [my emphasis], the “movies,” style, and philosophy and many other things which he protested he didn’t know anything about.’”