The Full Court Press of the Black Athlete

A new book tells how Black ballers changed professional basketball in more ways than we think we know.

September 30, 2025

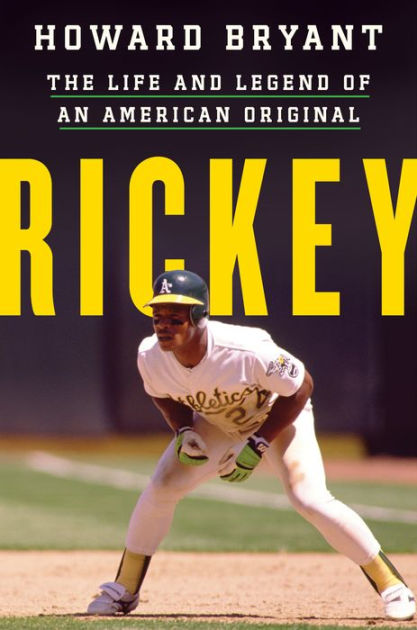

Black Ball: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Spencer Haywood, and the Generation That Saved the Soul of the NBA

“Ain’t I free?” asked Spencer Haywood. “Are all athletes slaves to the system?” (77)

In 1970, Haywood won both Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player for the American Basketball Association. While leading the league in points and rebounds, he propelled the Denver Rockets from last to first in their division. The skilled power forward proved the fledgling league’s marquee attraction, and he enjoyed the fruits of pro sports stardom, including a big luxury car, a closet full of hip clothes, copious women admirers, and all the jazz records he desired.

And yet: Ain’t I free?

Basketball had entered the age of Black Power, with Haywood embodying both its promise and perils. He had bucked established practice by turning pro before exhausting his four-year college eligibility, and after signing three separate contracts with Denver, he ditched the ABA for the Seattle Supersonics of the NBA, which still considered him ineligible, because his college class had not yet graduated. So Haywood launched an antitrust suit, and the US Supreme Court ruled in his favor.

Most reporters cast Haywood as entitled and misguided, a young rebel who was rupturing the stable arrangement between the NBA and the NCAA. But Haywood insisted that he operated from principle. At the University of Detroit, he had chafed under an authoritarian White coach who alienated Black players. In the ABA, he felt manipulated into signing exploitative, below-value contracts, and he overheard the team owner proclaim that “he wasn’t going to let ‘that Black nigger’ push him around.” (70)

Ain’t I free?

In leaving college, demanding new contracts, and filing an antitrust suit, Haywood was challenging a labor system built on paternalism. He was asserting control over his work, his worth. He was demanding a kind of freedom.

• • •

As commonly portrayed, pro basketball in the 1970s suffered from Black athletes who lacked not only the dignity of 1960s pioneers such as Bill Russell or Elgin Baylor, but also the mass-marketability of 1980s icons such as Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. The popular memory of pro hoops in this era includes accounts of contract-jumping, on-court fighting, and cocaine-sniffing.

Theresa Runstedtler’s Black Ball seeks to dislodge this conventional narrative. It casts the decade as one of significant progress, driven by Black athletes. Runstedtler argues that “they led the fight for free agency and a greater share of the profits. They introduced the moves and attitude of Black street basketball to the league. Above all, they demanded respect as professionals and as men—on their own terms.” (3) These developments prompted counterattacks from the White sports establishment, but they shaped the NBA that would captivate sports fans across the world.

By the mid-1970s, African Americans constituted over 60 percent of NBA rosters and most of its All-Stars. The Black dominance in basketball invited new possibilities, along with new pressures. Black Ball profiles some of the decade’s biggest stars.

At the decade’s dawn, Runstedtler paints a shifting landscape of race, labor, and the law. Even before Spencer Haywood’s suit, Connie Hawkins won an antitrust battle against the NBA—the league had banned him after a forced confession to point-shaving while at the University of Iowa, and after a near decade in exile, wasting his prime, Hawkins finally gained reinstatement to the league. Meanwhile, the lawsuit Oscar Robertson et al. v. NBA blocked the merger of the NBA and ABA, which would have driven down player salaries. By the time the merger was finally consummated in 1976, the players association won key concessions, including the eventual rise of free agency. Robertson, the lead plaintiff, represented the generation that resented the paternalism of NBA owners, which was inevitably shaped by racial dynamics.

By the mid-1970s, African Americans constituted over 60 percent of NBA rosters and most of its All-Stars. The Black dominance in basketball invited new possibilities, along with new pressures. Black Ball profiles some of the decade’s biggest stars. After converting to Islam, Lew Alcindor changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, while insisting on living on his own terms, independent of prevalent White expectations.

Earl Monroe injected the creative flourish of playground basketball, while Julius Erving delivered airborne majesty. Black figures started finding more leadership roles, too: Simon Gourdine became the league’s deputy commissioner, Wayne Embry the general manager of the Milwaukee Bucks, and Al Attles and K.C. Jones the head coaches for the teams in the 1975 NBA finals.

Yet as Runstedtler emphasizes, basketball bore a backlash. Black players faced the prejudices of White reporters, while coaches and executives found fewer opportunities for advancement than their White counterparts. When Kermit Washington smashed the face of Rudy Tomjanovich with a surprise punch during a 1977 on-court brawl, it prompted a media uproar, with Black athletes demonized as brutes. At the decade’s close, a controversial story in The Los Angeles Times speculated that 40 to 75 percent of NBA players used cocaine, fueling the perception of a league populated by spoiled, reckless men—including Spencer Haywood, whose drug addiction led to his banishment from the Los Angeles Lakers during the 1980 NBA finals.

Ain’t I free? Throughout Black Ball, Runstedtler grapples with that question. She locates the new channels carved by a generation of Black athletes, as well as the dams blocking them.

• • •

Black Ball is compelling narrative history, written with clarity and passion. Among its virtues, it weaves the story of Black basketball with the larger developments of American history during its “forgotten decade.” For example, it ties the resentment of Black sports millionaires to the declining economic power of White male workers amidst the transition from an industrial to a service economy. It connects racialized press depictions of cocaine and marijuana scandals to a political climate shaped by Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs.” It quotes Roger Stanton of Basketball Weekly, who echoes the language of political conservatives as he defends Jim Harding, the hard-line coach of Spencer Haywood, who later faced a player revolt at the University of Detroit: “We are a nation of law and order—in the streets and on the athletic fields. Let us never forget that.” (74)

Runstedtler effectively juxtaposes these conservative opinions with those of Black players and writers, reflecting the polarized conversations around sports in the 1970s. She spotlights not only columnists from the Black press such as the venerable Sam Lacy, but also the new magazine Black Sports, which embraced the style and politics of the athletes. During the legal challenge to block the NBA-ABA merger, for instance, Black Sports featured a roundtable that took seriously the perspectives of players such as Joe Caldwell and Oscar Robertson.

Black Ball is compelling narrative history, written with clarity and passion. Among its virtues, it weaves the story of Black basketball with the larger developments of American history during its “forgotten decade.”

Runstedtler’s most delicate balancing act concerns the depictions of the players at the center of her story. On one hand, she describes the problems that engendered controversy: Spencer Haywood did sign contract after contract, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar did act prickly with the press, Kermit Washington did punch Rudy Tomjanovich, Bernard King did derail his career due to drug addiction. On the other hand, she explains how the White-dominated media kept filtering these stories through lenses distorted by racial bias. In each case, Runstedtler reframes the history through a Black perspective, arguing for fairness and compassion in our understanding of their struggles, while emphasizing their contributions to the forging of the modern NBA.

• • •

Runstedtler has her own personal connection to the NBA. In the late 1990s, she joined the Toronto Raptors Dance Pak, providing in-game entertainment for fans of the league’s latest expansion franchise. Over time, she noticed that the dance team got “skinnier, whiter, and blonder,” and its hip hop style got muted. (11) During her second year, failed labor negotiations led team owners to impose a lockout. As the players endured negative publicity, the dancers lost paychecks. Two decades later, after a Ph.D. in History and African American Studies at Yale and the publication of Jack Johnson: Rebel Sojourner, a global history of the Black boxing icon, Runstedtler returned to the NBA as a scholar, determined “to make sense of what I became a part of in the late 1990s.” (11)

Runstedtler reflects on a league that places “Black Lives Matter” on its courts and trumpets its initiatives on racial justice. She asserts that these developments relied on the initiatives of the athletes who stand at the game’s center.

As Black Ball so aptly reinforces, the NBA has flourished in concert with the rise of the Black athlete, even as those same athletes decry the racial double standards that infect sports and society. The league’s commercial explosion, starting in the 1980s, depended on marketing Black style for a wider national and international audience. Through Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan, through Shaquille O’Neal and Allen Iverson, through LeBron James and Steph Curry, the NBA has neither embraced nor ignored Black culture—rather, it has harnessed and contained Blackness.

Runstedtler reflects on a league that places “Black Lives Matter” on its courts and trumpets its initiatives on racial justice. She asserts that these developments relied on the initiatives of the athletes who stand at the game’s center. “If the NBA now has a reputation for being not only the coolest but the most progressive of all the U.S. professional leagues,” she writes, “it’s because the players made it so by fighting against the paternalistic and profit-driven practices of the white basketball establishment.” Black Ball carries this dynamic back to the 1970s.

Ain’t I free? The context changes over time, but the question always deserves to be asked.