The Curious Second Act of Chuck Colson

The disgraced special counsel to President Nixon found redemption in U.S. public life after Watergate, but the details are more complicated.

By Ben Fulton

November 29, 2025

Coming of age in the United States during the 1970s and 1980s, when Americans who professed agnostic or atheistic beliefs risked borderline accusations of “godless communism,” Sunday-school kids from believing families knew who their role-models were.

Roman Catholic kids had the Pope and their saints, along with Mother Theresa. Upper-class mainline Protestant kids, the Lutherans and Episcopalians, could tell you all about Albert Schweitzer, the German scholar, musician, and physician who divided his life between studying the music of Bach and a medical mission in Africa. Mormon kids could recite the lives of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young by heart. As a teenager whose family went back and forth between mainline Protestant churches and more fundamentalist Evangelical churches comprised of little more than cinder blocks and folding chairs, my heroes of faith rotated among four figures. There was Johnny Cash, the entertainer who found God after too many amphetamine-and alcohol fueled nights on the road. There was Joni Eareckson Tada, the young woman who found herself paralyzed from the neck down after a diving accident, but found God and an art career sketching and painting with pencils and brushes clenched between her teeth. There was Corrie Ten Boom, the valiant Dutch girl whose family gave Jews assistance and shelter during World War Two.

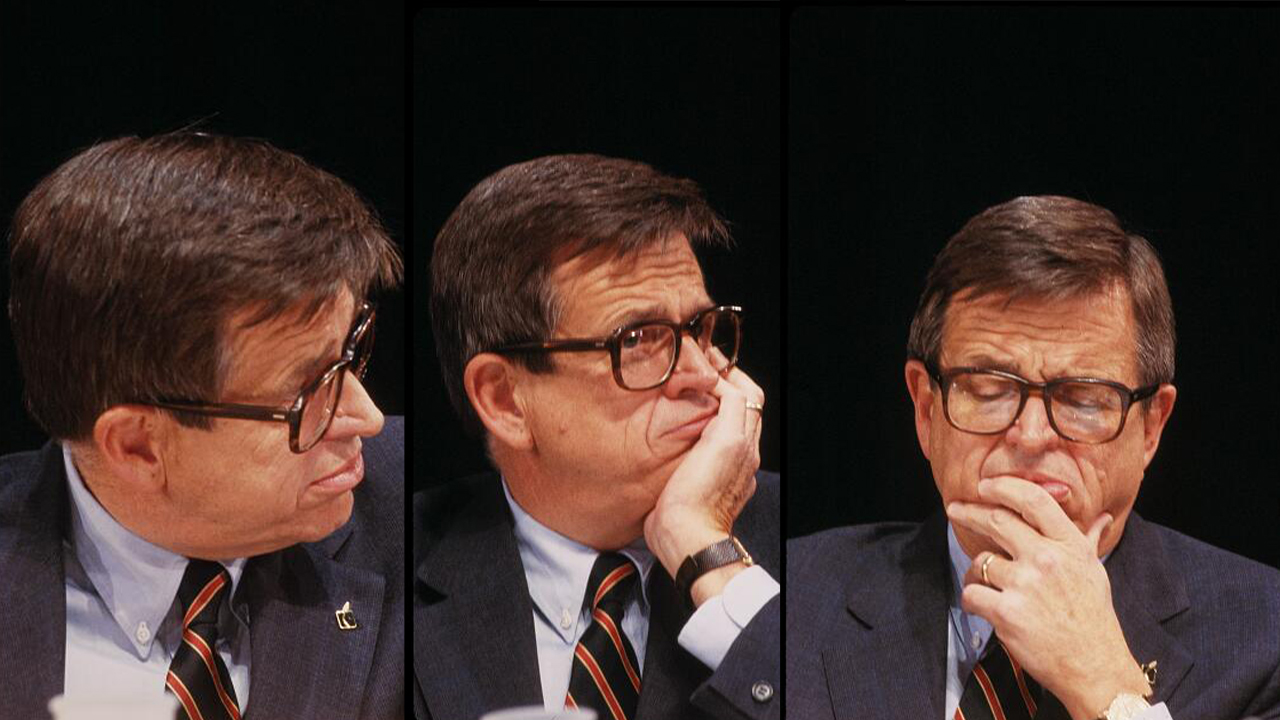

First and foremost, though, there was Charles “Chuck” W. Colson, the owlish-looking special counsel to President Richard Nixon who survived the Watergate scandal and a prison sentence to found the Landsdowne, Virginia-based Prison Fellowship Ministries.

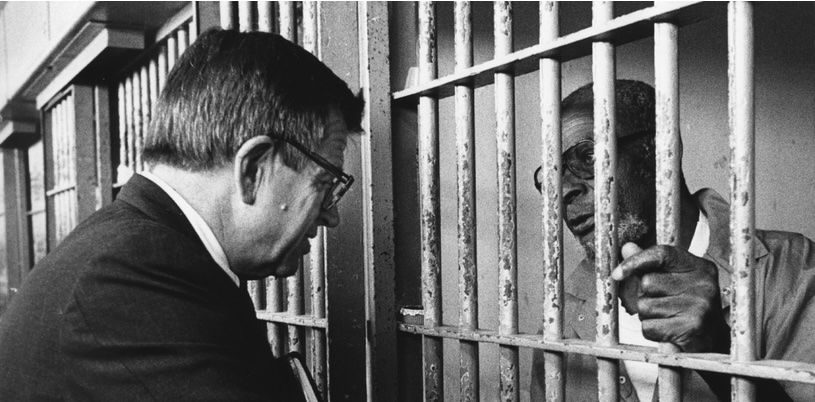

Colson was respected and adored by Evangelical congregations in the late 1970s, and up to his death in 2012, in ways hard to define or even describe in the context of today’s U.S. political and religious climate. Trump-era Evangelicals seemingly embrace their faith as an act of spiritual warfare, in which abortion, LGBTQ culture, and “woke” feminism and racial identities must be extinguished in every corner of American life. In the late 1970s, and for most of the two decades to follow in which abortion persisted but was not yet center-stage in Christian life, and in which the gay community was more preoccupied with fighting the AIDS epidemic than lobbying for marriage rights, Evangelicals seemed far more focused on the old-fashioned pursuit of “saving souls.” Colson certainly fit that camp, distributing Bibles through prison-cell bars and speaking from the pulpit about “the power of Christ” to save sinners and transform lives.

Congregants knew and talked about how Colson had “done wrong.” No one, however, talked too much about what his misdeeds consisted of. Instead, we were led to marvel about how one man, doggedly hunted by Nixon’s enemies, had found the moxie and means—through the saving power of Jesus—to pick himself back up and get back in the game. It was almost as if Colson’s newfound respect was a sort of revenge on those who believed he was nothing more, perhaps even less than, an opportunist who just happened to find religion a convenient tool at the right time.

Prison Fellowship Ministries pamphlets graced by Colson’s genteel visage bristled from literature racks and church pews my family attended over the years. Prison Fellowship Ministry activities and fund-raising appeals never failed a hearty pastoral mention at the pulpit. Few were the number who acted on Colson’s example to minister face-to-face inside prisons. But far more opened their wallets and purses to Colson’s cause, my mother included, who read several of his more than twenty book titles.

Congregants knew and talked about how Colson had “done wrong.” No one, however, talked too much about what his misdeeds consisted of. Instead, we were led to marvel about how one man, doggedly hunted by Nixon’s enemies, had found the moxie and means—through the saving power of Jesus—to pick himself back up and get back in the game.

The most cursory read of Colson’s biography reveals a post-incarceration record almost beyond reproach. The “hatchet man” for President Nixon, and a chief architect of both Nixon’s “dirty tricks” and the team of “Plumbers” who schemed to smear, libel, drug, and, in at least one case, even assassinate the president’s vast list of “enemies,” lived not just to endure the stain of a criminal conviction and seven months in federal prison, but seemingly transcend it.

Before being awarded the 1993 Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion, Colson garnered fifteen honorary doctorates. Married to a Roman Catholic woman after his first marriage ended in divorce, he orchestrated ecumenical efforts between Evangelicals and Roman Catholic leaders. By most accounts, Colson donated his many book royalties and award-money prizes back into the cause dearest to his heart when he became a born-again Christian: to treat the U.S. prison population with dignity and ensure that their authentic rehabilitation took precedence over punishment. One Christian title, Seven Men and the Secret of Their Greatness by Eric Metaxas, put Colson in the rarified arena alongside George Washington, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Jackie Robinson, and Pope John Paul II. Colson reached the culmination of his own rehabilitative journey in 2008, when President George W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Citizens Medal.

“I do not treat this medal as mine,” Colson said at the time, in the spirit of Christian selflessness. “It is, like in the military, a unit citation. The staff of Prison Fellowship, the thousands of volunteers, and the hundreds of thousands of donors have made this possible. So while I am overwhelmed in gratitude to God, I am grateful to all those associated in this movement called Prison Fellowship.”

• • •

Even today, Colson seems a Christian example better lauded than scrutinized. Examining his legacy now, years after growing up in the shadow of his public presence, has for me been an exercise in discovering not just what I accepted from my peers and adults growing up Christian, but an investigation into the nature of rehabilitation and one man’s second act. Certainly, most people who profess to reform themselves before endeavoring to reform others deserve a hearing, however short. In today’s hyper-partisan political climate, though, what might intrigue us most is that Colson, among the most firebrand Republican partisans of his time, found a way out of the political impasse and morass of his time in a way that remains unique. Colson was shamed enough in his past actions on behalf of a corrupt administration to plead guilty to obstructing justice and defaming someone deemed an “enemy” to the president he served under. Colson achieved his second act in life through Christianity, an institution and tradition respected in the United States as in almost no other country, but to hear him tell it in articles and books relating his story over the years, his faith was never a means, but a glorious end he stumbled upon as the claws of political scandal descended on his life.

It is still considered bad form by most Americans to question a person’s religion, but there is little question that Colson omitted certain facts of his infamous political past on the way to his public transformation. None of these omissions blot his legacy entirely, but neither do they serve as evidence that he was ever completely—perhaps authentically—penitent of all he said and did at the ruthless command of the first U.S. President ever to resign from office in disgrace.

Most of us, if we are honest, strive for reputations in which the shadow of our worst mistakes is never revealed or held to account. But most of us are not so lucky—or, dare it be said, calculating?—as Chuck Colson.

• • •

The story of Colson’s notorious professional life begins in 1950s Massachusetts, home to his Boston birthplace in 1931, and the state Republican Party in which he cut his teeth. As Colson describes it in his best-selling 1976 autobiography, Born Again, working the media and smearing your opponent for the underdog party in a state where Irish and Italian Democrats held power was simply part of the game. A “Swamp Yankee” rather than a “new ethnic,” Colson recounts that he came of age in a kind of siege mentality, a resentment of East Coast intellectualism, and a work ethic in which he always felt the need to prove himself.

By the time he reached Nixon’s White House after a law degree from George Washington University and service as a U.S. Marine in Guatamala Colson had cultivated a driving need for acceptance equal to the president he long hoped to serve: “Nixon and I understood one another … prideful men seeking that most elusive goal of all—acceptance and the respect of those who had spurned us in earlier years.” (Born Again, 37)

Arm-twisting, making deals, and smearing opponents to build up allies and friends, both in Massachusetts and Washington D.C., is described in Colson’s autobiography as the only politics he knew, and also enjoyed. One of Colson’s first big acts of political warfare on President Nixon’s behalf was calling on AFL-CIO union leaders to organize the May 1971 “Hard Hat Riot” of construction workers who clashed with student anti-war protesters in New York City. The result was more than 70 people injured, a fact Colson omits in his autobiography. What Colson recalls instead was how the strife he orchestrated resulted in telegrams of support “flooding the White House,” along with the “unprecedented political alliance between a Republican President and organized labor.” (47)

Colson achieved his second act in life through Christianity, an institution and tradition respected in the United States as in almost no other country, but to hear him tell it in articles and books relating his story over the years, his faith was never a means, but a glorious end he stumbled upon as the claws of political scandal descended on his life.

Except for the label of “Watergate” itself, none of the various plots hatched by the Plumbers Colson helped recruit and manage to inflict pain and libel on Nixon’s enemies seems worth mentioning. Not Operation Gemstone. Not the plot to firebomb the Brookings Institution. Not the plan to fabricate U.S. State Department cables in order to name President Kennedy as having ordered the assassination of the President of South Vietnam. There is no mention of the Plumbers’ blood-chilling plan to assassinate Washington journalist Jack Anderson, only fleeting mentions of Anderson’s adversarial role with Nixon’s White House. Over more than 370 pages, the only misdeed Colson mentions in a modicum of detail, and the sole charge which he was later to plead guilty, was his plan to discredit Daniel Ellsberg. The leaker of the Pentagon Papers documenting U.S. duplicity in the Vietnam War, Ellsberg was on trial for unlawfully releasing the trove of classified documents. Nixon was infuriated, with Colson called on to smear Ellsberg at any cost. As Nixon put it in a phrase used repeatedly in front of his White House aides, and that would later tar his legacy, “I don’t care how it’s done.”

Curiously, Colson’s sole guilty plea dovetails with how he became a professing Christian soon after reading C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity. “The lowliest individual was more important than a state or nation!” Colson remembers from reading Lewis. “Then, hard as it was to stomach, I had to admit that Dr. Daniel Ellsberg’s rights were more important than preserving state secrets.” (141)

Throughout Colson’s workman-like autobiography, published just one year after his release from seven months in federal prison, the mood swings between borderline fond remembrances of all he did on behalf of a president and party he was loyal to, followed by bouts of regret for all he did that was motivated by pride, a sin Colson lashes at repeatedly:

I knew how to spin a story, whether doing “damage control” by taking something questionable we had done and giving it a positive twist, or mustering up some “dirt” on a person we considered a political rival. I was not as sure about writing the raw, unvarnished truth about myself and how I had fallen into disgrace.

What motivated me was that my disgrace was not the end of the story—or even the main part of the story. The real story was that Christ had reached down to me, even in my disgrace and shame, and revealed Himself as the One who forgives and makes new. …

For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God—whether they stand at the heights of political power or the depths of prison confinement. I have been in both spots. (10)

Born Again, then, is both a confession and a defense. A document of partial guilt but also an explanation. Some would call it an excuse, even if that, too, is also partial. What saves the book from becoming an exercise in self-pity is not just the window into moments when Colson admits responsibility, but the demeanor in which he constantly describes himself as surrendering to God’s “will and plan.” As Colson enters his plea before a judge, awaits sentencing, and serves his sentence between prisons in Baltimore and Alabama, the fate of his colleagues in subsequent Watergate trials shrinks from view as so much unsavory mob justice, which he compares to “members of the French aristocracy made to kneel before the blade two hundred years earlier.” (358) Replacing his anxieties over Nixon and Watergate are the conditions of prison life and the injustices endured by various inmates he meets on work detail and in the mess hall. Colson is appalled at how inmates are treated, along with the injustices they often suffer:

Just as God felt it necessary to become man to help His children, could it be that I had to become a prisoner the better to understand suffering and deprivations? If God chose to come to earth to know us better as brothers, then maybe God’s plan for me was to be in prison as a sinner, and to know men there as one of them. …

For the rest of my life I would know and feel what it is like to be imprisoned, the steady, gradual corrosion of a man’s soul, like radiation burning away tissue. Just as God in the Person of Christ was not ashamed to call us His brothers, so it was that I should not be ashamed to call each of these fellow inmates my brothers. Furthermore, I was to love each one of them. And would I—if I had not been here? Never, I admitted to myself. (307-308)

So far, so transformational. But what, we may ask, becomes of the larger lessons about the abuses of government power? Are there no secular lessons for Colson to learn and pass on?

Apart from languishing intermittently over his own guilt in depriving Ellsberg the right to a fair trial by attempting to smear his name, Colson is mostly too busy rejoicing in the glory of his newfound faith. Generous readers would say that it is a person’s rightful prerogative. A skeptic who remembers the outrageous plots and outright crimes of the Nixon administration, even if now more than 50 years in the past, would rightly demand a bit more from a guilty conscience. But if there is one central lesson to glean from the case of Chuck Colson, it is that the chance and terms of rehabilitating character vary greatly. When society grants us that chance, and later deems a reformation of character complete, there is no one-size-fits-all in dispensing grace, mercy, and forgiveness.

• • •

Historians of Watergate have not been nearly so kind to Colson’s record as have Colson and his fellow travelers in Evangelical Christianity. Nor has Daniel Ellsberg who, after Colson’s death in 2012 and before his own passing in 2023, told the press: “I have no reason to doubt his evangelism, but I don’t think he felt any kind of regret.” (“Charles Colson, Nixon counsel, dies,” April 21, 2012, Associated Press)

Most accounts of Watergate, and two books in particular, ensure that even if Colson is remembered most for his prison ministries, his previous reputation has a permanent record.

British journalist Fred Emery, who, along with The Washington Post team of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, earned the majority of scoops as the Watergate scandal unfolded, described Colson as Nixon’s “one-man presidential interest group” in his 1994 tome, Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon.

Throughout the entire Watergate scandal, not just the break-in at the namesake hotel, Emery names Colson at almost every turn. Colson personally recruited former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt—along with G Gordon Liddy, the most ruthless of Plumbers. (73) It was the cunning of Colson to suggest that his team stage a fire alarm at the Brookings Institution for FBI agents to gain entry and seize documents Nixon wanted. (48) Colson teamed with John Dean, another of Nixon’s White House counsel, to compile Nixon’s infamous “enemies list.” (27) Colson not only fed Washington journalists defamatory information about Ellsberg, but knew in advance, in a memo from Hunt, of the plot to break into the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, Ellsberg’s psychiatric analyst, in search of dirt. (69). Colson fed forged U.S. State Department cables to the press, including The New York Times, implicating the Kennedy administration in a direct conspiracy to assassinate South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963. (Nixon was at the time convinced that Kennedy ordered Diem’s murder but could not confirm his suspicion with evidence. Nixon’s suspicion would prove prescient decades later, though, when taped evidence surfaced to confirm President Kennedy’s role in Diem’s assassination. At the time, however, Nixon had no proof and relied on Colson’s fabricated cables to propagate the rumor.) (72) Finally, Colson was enthusiastic enough about Hunt and Gordon Liddy’s Operation Gemstone to at least press others on a decision for its implementation, and probably admired it enough to fund it. A litany of various plots to embarrass, snag, or otherwise cripple Democratic party operations during the 1972 election year, its extensive list of covert operations and illegal acts involved everything from kidnapping to drugging, bugging, mugging, hiring out prostitutes, and enlisting hippies to urinate on campaign office carpets during the Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida.

If there is one central lesson to glean from the case of Chuck Colson, it is that the chance and terms of rehabilitating character vary greatly. When society grants us that chance, and later deems a reformation of character complete, there is no one-size-fits-all in dispensing grace, mercy, and forgiveness.

Described by Emery as “a political bruiser,” Colson never forgot the Green Beret motto he learned in the U.S. Marines because he kept it pinned on his wall: “If you’ve got ’em by the balls, the hearts and minds will follow.” (31) Emery notes that Colson’s eventual guilty plea to “obstructing justice by attempting to defame Ellsberg” was, in fact, the outcome of legal bargaining. Originally charged, along with John Ehrlichman, a man of many hats in the Nixon administration, and the Plumbers for the break-in at Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, Colson’s guilty plea resulted in all other charges against him being dropped. (433) Nor did Colson ever come close to testifying against Nixon. (433). Yet, Emery notes, Colson’s guilty plea was “symbolic” of a crucial breaking point in the scandal. The hard-nosed “Swamp Yankee,” who once bragged he would run over his grandmother to re-elect Nixon, was “the first of the president’s inner circle to have accepted that what he had done in Nixon’s service was illegal, and it tightened the political noose.” (434)

Garrett M. Graff’s 2022 book, Watergate: A New History (Simon & Schuster), researched and written in the light of the full release of Watergate and Nixon White House tapes since 1993, is even less forgiving of Colson’s wallow in devious and illegal schemes. The most damning revelation by far is Colson’s order to Hunt that Washington journalist Jack Anderson, whom Colson once proposed that documents be forged to tarnish as a homosexual, be “stopped at all costs” by the Plumbers. (135) That broad, but implicit message to Hunt, who called Colson “my principal,” was received as an order to assassinate Anderson. (135-136)

In addition to all the schemes and sins Emery links to Colson, Graff lists several more. They include additional plans to break into the Brookings Institute and steal documents (70, 95), the destruction of evidence that would tie the Plumbers to Nixon’s White House (204), White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman’s memory that Colson originated the idea to wiretap the Democratic National Committee (181), and Colson’s attacks on Katharine Graham of The Washington Post and the FCC broadcast licenses it owned in subsidiary TV stations. (288) That particular threat by Colson drew tangible results, Graff notes, cutting the Post’s stock value by half.

As in Emery’s account, Graff describes how Colson “felt weighed down by a guilty conscience, but not for the crime he’d been charged with.” (608) Again, the legerdemain of guilt Colson wanted to perform—not wholly deceptive, but not entirely honest, either—was the act of getting to decide for himself what he did wrong. In all the chapters and verses of his redemption in the public eye, under the harsh glare of Watergate, Colson himself would call the shots. (Or do his damn best trying.) With God by his side, of course. Perhaps the fact that he authored more than 20 books after his release from prison is testament that Colson wanted to have the last word, and plenty of them.

In a concise statement after his guilty plea, published June 14, 1974, by The New York Times, Colson took issue with anyone who questioned his motives. Most of it amounts to a polite, yet stern, rebuke of prosecutors who indicted him. He alone can affirm and admit to what he is guilty of, and “I have taken this action for reasons which are very important to me.” He did not testify fully to the Ervin committee investigating the scandal, Colson implies, out of fear that it would result in far worse indictments than those originally delivered. In the middle of his statement, Colson plays the victim, stating, “I know how it feels to be subjected to repeated and in some cases deliberate leaks from various Congressional committees.” He dispels any notion that he traded testimony—“‘useful’ against others,” as he put it—for plea bargaining. In other words, Chuck Colson is no rat, and loyal to the end, where the Nixon administration is concerned.

But then, after a second bizarre detour, in which he alleges the CIA smeared him in the press, Colson ends by turning to his newfound sense of civic duty and fair play: “I truly believe that out of all the agonies of Watergate, it is possible to bring about important changes in our political process and to strengthen our institutions in such a way that they are better protected against those who would abuse the political process or abuse their public trust.”

Soon after he emerged from prison to become a leading light in U.S. Evangelical culture, Colson could have brought those “important changes” into reality. Possible, but not probable, given his enthusiasm instead for prison ministries and evangelism itself. We can give Colson his due. Having had enough of the guilt necessary to remake his life, he followed his joy. After the 2008 death of Mark Felt, three years after being revealed as the “Deep Throat” oracle of anonymous information that unleashed Watergate, Colson revealed perhaps his truest colors of all regarding his past. Colson did not exactly scald Felt’s legacy, but he certainly chided him. “He [Felt] goes out of his life on a very sour note, not as a hero,” Colson said to NBC.

The legerdemain of guilt Colson wanted to perform—not wholly deceptive, but not entirely honest, either—was the act of getting to decide for himself what he did wrong. In all the chapters and verses of his redemption in the public eye, under the harsh glare of Watergate, Colson himself would call the shots. (Or do his damn best trying.)

Unsurprisingly, many Democrats, and certainly left-wing progressives, showed their own uncharitable side toward Colson as he ingratiated himself with the second Bush administration’s faith-based efforts of charity in the early part of the new century. Gradually, but surely, Colson over the years slipped into the more doctrinaire aspects of his faith: opposition to abortion, hostility to rights for gays and lesbians, campaigns in favor of “intelligent design” school curriculum skeptical of evolution by natural selection, and, after 9/11, a lean into Islamophobia.

Whether on the left or right, agnostics often forget that Christians will be Christians. Or, as novelist Philip Roth once reminded a symposium of Roman Catholics at Loyola University in Chicago in his 1961 lecture, “Some Nice Jewish Stereotypes,” religion itself is rarely a partisan-free endeavor. Roth’s description of the committed Jew in a world dominated by believing Christians remains true even when the roles are switched: “The fact is that if one is committed to being a Jew, then he believes that on the most serious questions pertaining to man’s survival—understanding the past, imagining the future, discovering the relation between God and humanity—that he is right and the Christians are wrong. As a believing Jew, he must certainly view the breakdown in this century of moral order and the erosion of spiritual values in terms of the inadequacy of Christianity as a sustaining force for the good. However, who would care to say such things to his neighbor?”

There is also the temptation to compare Colson to other resuscitated figures of the Watergate scandal. Jeb Magruder, deputy director of Nixon’s Committee for the Re-Election of the President, traced his post-Watergate life along lines almost identical to Colson’s. After pleading guilty to conspiracy to wiretap, obstruct justice and defraud the United States in 1973, Magruder became an ordained Presbyterian minister. Then there is G Gordon Liddy, pardoned by President Jimmy Carter after 4 years in federal prison after being convicted of illegal wiretapping, burglary, and conspiracy. Shameless, thuggish, and indecent to the end of his life in 2021, Liddy, like Colson, authored a string of books once back in civilian life, none striking a contrite or penitent note. Brandishing rhetoric of federal agents as “jackbooted thugs,” he brayed and barked to the right wing on talk radio, where he once mused about shooting Hillary Clinton in the head. Liddy landed assorted cameo acting roles in film and TV, assorted business ventures, and otherwise basked in his reputation as Watergate’s most notorious, unhinged figure.

Colson noted in Born Again that he had a ready answer to anyone who doubted the sincerity of his new life, or otherwise charged him of “hiding behind God” to dodge larger blame and responsibilities. “If anyone wants to be cynical about it, I’ll pray for him,” he said. (183)

Colson admitted it sounded patronizing, even arrogant. But as the first thought “that had popped into my mind” when someone doubted his “sincerity,” it also had the ring of truth. (183) At least to his ears.

Through all his prevaricating over what he did, or did not do, during the Nixon years, through his insistence of guilt here but innocence there, and onward through his decades of life in his newfound faith, Colson surely wanted others to share in the truths he found as a Christian. But perhaps more importantly, he knew that the one person you must be true to through the trial and turbulence of a second chance in life is yourself.

Sources:

Charles W. Colson, Born Again (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Chosen, Baker Publishing Group, 1976, reprinted with new introduction 2008)

Fred Emery, Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon (New York: Times Books, Random House, 1994)

Garrett M. Graff, Watergate: A New History (New York: Simon & Schuster, Avid Reader Press, 2022)