Norman Rockwell died forty-three years ago today. As a visual storyteller he had few peers, and his timing was good, too. His lifespan (1894-1978) tracked the rise and fall of illustrated magazines with striking precision.

The fusty family house magazines like Harper’s Monthly, Century, and Scribner’s Magazine began to give way to cheaper, more timely publications like Munsey’s just as Rockwell entered the world in the mid-1890s. The young Rockwell and modern American consumer culture matured at much the same rate. By the time his career was taking off, the publishing and advertising industries had collaborated to build a dominant, lucrative medium: the illustrated magazine. In 1916, at twenty-two, Norman sold his first illustration to George Lorimer, the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post.

Today, many would be astonished to learn that American magazines pumped out lavishly illustrated fiction for adults, week after week, month after month, across many decades. A cursory glance at the table of contents for any issue of, say, The Ladies’ Home Journal published between 1900 and 1960, reveals a lineup of five or six short stories as well as a serialized novel or two, all illustrated. Competing titles offered the same. As time wore on the illustrations grew larger and more colorful, the lettering announcing each title increasingly striking. In later decades these swashbuckling introductory spreads came two pages at a time in a consecutive flurry, each leading to a conclusion at the back of the issue. After an opening flourish, readers would be invited to “see page 129,” or the like, where the story resumed and resolved.

These magazine fiction gigs sustained many illustrators. By pure volume, they defined most of the popular market. The same publications—both general interest magazines, like The Saturday Evening Post, and women’s mags like the “seven sisters” (LHJ, Woman’s Home Companion, Good Housekeeping, etc.)—also ran plentiful ads which often mimicked the visual style of the story illustrations (and sometimes were produced by the same artists). The story illustrations and the pictorial advertisements were both responses to texts; they were expected to enliven, sharpen, complement, or underscore messages otherwise delivered with words. Conventionally speaking, these were the duties of a professional illustrator.

These magazine fiction gigs sustained many illustrators. By pure volume, they defined most of the popular market. The same publications—both general interest magazines, like The Saturday Evening Post, and women’s mags like the “seven sisters” (LHJ, Woman’s Home Companion, Good Housekeeping, etc.)—also ran plentiful ads which often mimicked the visual style of the story illustrations (and sometimes were produced by the same artists). The story illustrations and the pictorial advertisements were both responses to texts; they were expected to enliven, sharpen, complement, or underscore messages otherwise delivered with words. Conventionally speaking, these were the duties of a professional illustrator.

If Rockwell worked on many advertisements, he completed relatively few fiction illustrations (most notably, his Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn projects in 1936), almost none for magazines. Yet he was extremely productive. What, exactly, did the man who titled his 1960 autobiography My Adventures as an Illustrator, illustrate?

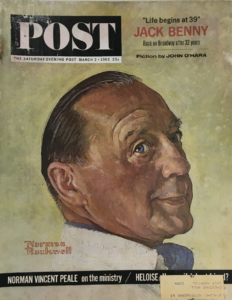

Norman Rockwell was known, above all, as a Saturday Evening Post cover artist. Between 1916 and 1963, he produced 323 Post covers—two more than the illustrator in whose footsteps he followed at the Post, J.C. Leyendecker. (The German immigrant Leyendecker got his start as a poster designer in the 1890s. When the early twentieth-century vogue for posters subsided, magazines awaited. Cover illustrations worked much the same as posters, and rewarded the same skills.)

A century ago, covers were not so much commissioned as pitched. Fiction illustrations were assigned by art directors, but covers worked more like cartoons: many were offered, few were published. Later, Rockwell brought cover ideas to Post editors, and executed finishes once the concepts were accepted.

Perhaps Rockwell’s covers might be seen as genre paintings: freestanding vignettes, independent of an editorial housing. I think not. His relationship with the Post involved more than the borrowed masthead. His task, played out across hundreds of covers, was to enliven and embody the editorial premise of the magazine, aimed at middle Americans in all corners of the country, overwhelmingly White and mostly Protestant. His job was to illustrate the identity of The Saturday Evening Post in oil on canvas (already an anachronistic medium by 1930, when gouache came into wide use). He was strikingly good at it; his covers guaranteed a bump in sales of 50,000 to 75,000 newsstand copies. Rockwell’s strongest work ran in the 1940s and the first half of the 1950s, as he came to integrate more complex settings and narratives.

When Theodore Peterson published Magazines in the Twentieth Century (University of Illinois Press, 1956) the data looked good. The future still seemed promising. But the bottom dropped out almost immediately. Collier’s went under in 1957. Many of the remaining American magazines folded or adapted during the early 1960s, weakened by a mixture of television, Betty Friedan, the civil rights movement, and editorial misjudgment. Illustration was greatly restricted, or put to different purposes.

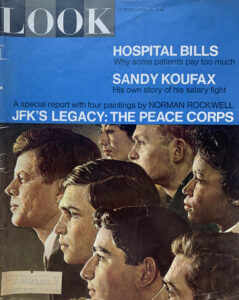

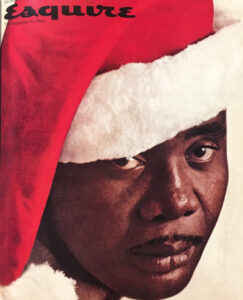

I have pulled a few of my favorite Rockwell covers for this post, but also the very last one: his March 2, 1963 portrait of Jack Benny. Headlines promise articles about Norman Vincent Peale and Heloise, the household maven. Against that trio, juxtapose the rapidly evolving editorial direction at Esquire: The same year, George Lois and Sonny Liston created the famous “Black Santa” cover. The Saturday Evening Post folded a few years later. Rockwell would catch on with Look for a final chapter, this time on interior features with more advanced social themes, a liberation from old strictures. But his most acute, capacious work was behind him.

I have pulled a few of my favorite Rockwell covers for this post, but also the very last one: his March 2, 1963 portrait of Jack Benny. Headlines promise articles about Norman Vincent Peale and Heloise, the household maven. Against that trio, juxtapose the rapidly evolving editorial direction at Esquire: The same year, George Lois and Sonny Liston created the famous “Black Santa” cover. The Saturday Evening Post folded a few years later. Rockwell would catch on with Look for a final chapter, this time on interior features with more advanced social themes, a liberation from old strictures. But his most acute, capacious work was behind him.

On the anniversary of his departure, a tip of the hat to Uncle Norman, whose latter-day appeal to the contemporary MAGA crowd ought not be held against him.