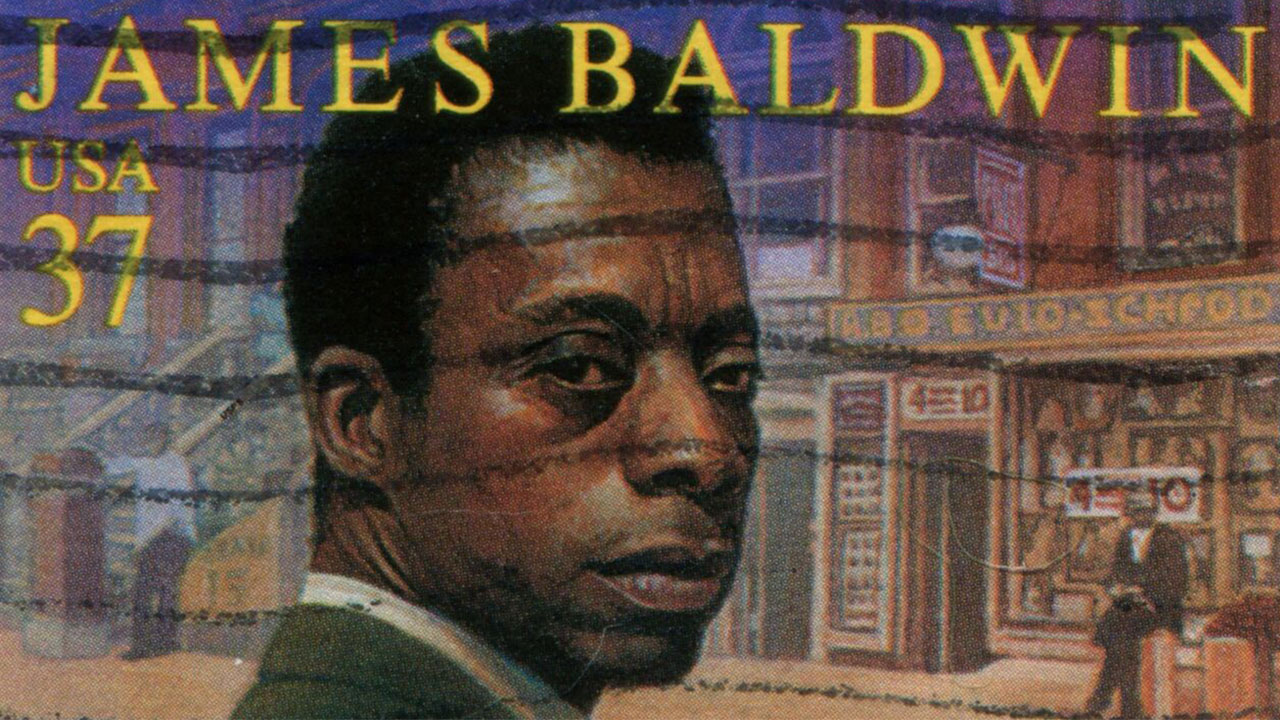

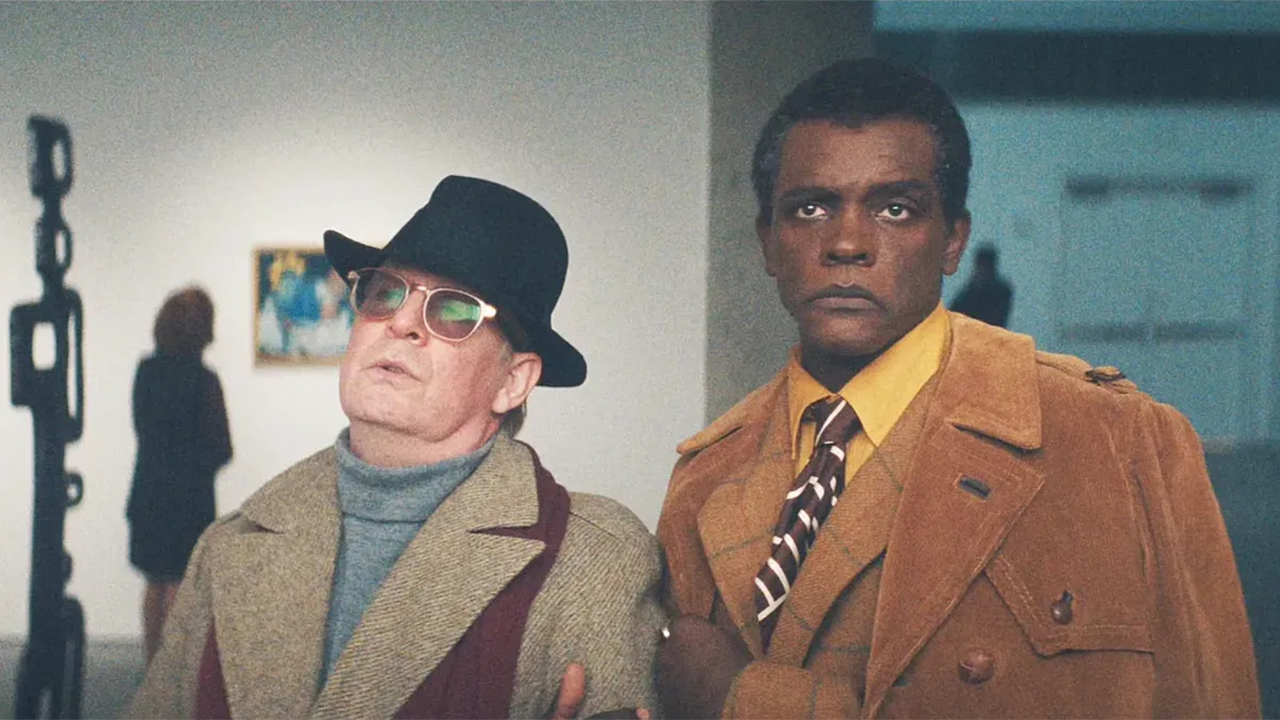

James Baldwin and Truman Capote

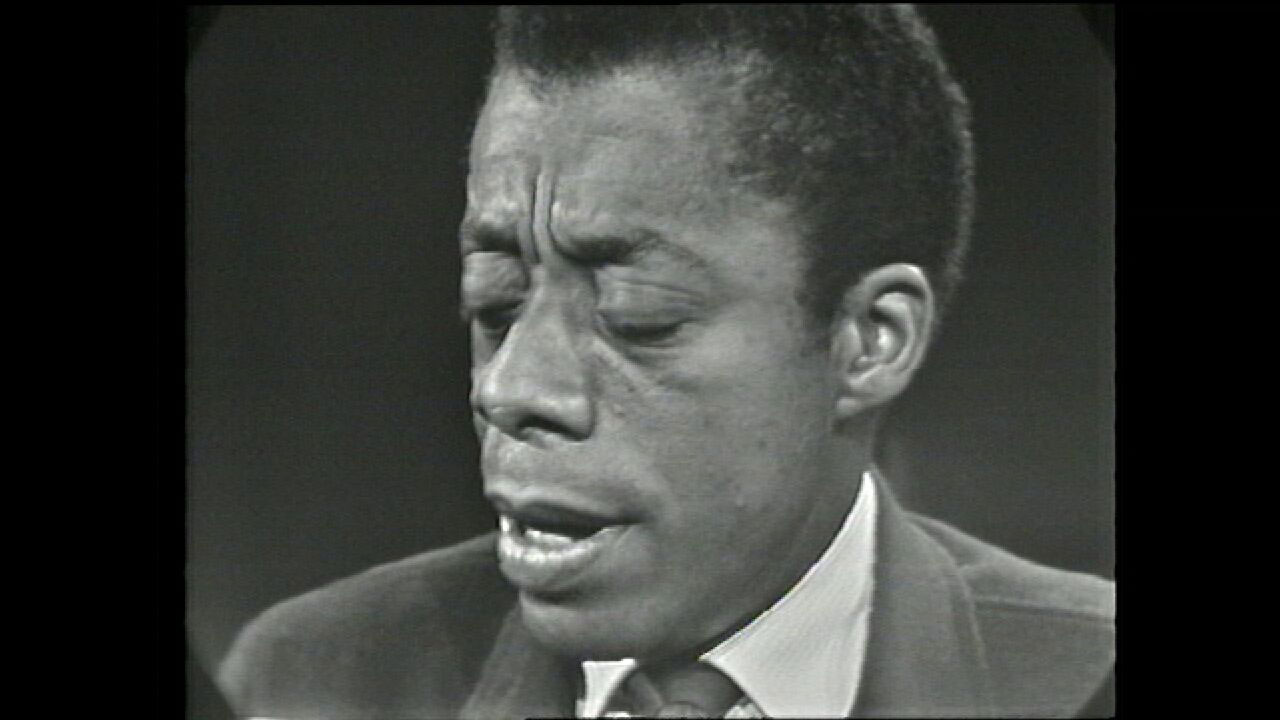

In 1976, James Baldwin showed up in Berkeley to visit me and we hung out and had a great time. Although he never mentioned Truman Capote, I am willing to bet that if I had asked him he would have said, “Yeah, I stopped off to see if you were here to see him on my way out of New York.” The fictional truth is a greater truth than any that we have in real life.