The term “power plant” often evokes images of giant nuclear cooling towers or massive fossil fuel smoke stacks reaching skyward. People’s thoughts tend towards massive infrastructure projects that produce energy for entire cities in a single location. As was touched on in Part 1 of this series (The Grid), as the electric industry evolved from its infancy, power plants grew larger and larger seeking greater efficiencies of scale. That began to change in the late 1970s.

The term “power plant” often evokes images of giant nuclear cooling towers or massive fossil fuel smoke stacks reaching skyward. People’s thoughts tend towards massive infrastructure projects that produce energy for entire cities in a single location. As was touched on in Part 1 of this series (The Grid), as the electric industry evolved from its infancy, power plants grew larger and larger seeking greater efficiencies of scale. That began to change in the late 1970s.

For the previous 90 years, electricity had been primarily generated in two forms: hydraulic power from hydroelectric dams, and steam power from fossil-fuel combustion. These two technologies benefit greatly from economy of scale, with larger generators providing the greatest return on investment. Turbines were built that could produce over a Gigawatt of power, generating electricity for a million homes with a single generator. However, two factors, one technological and one economic, began to shift new power plants away from the steam and hydraulic turbines.

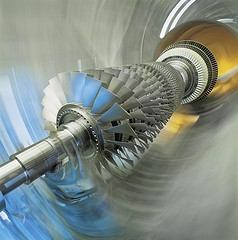

New types of turbines began to enter the market. Combustion and combined cycle turbines allowed for greater generating efficiencies without needing massive capacities. In a combustion turbine, the blades of the turbine are powered from the hot exhaust gases directly generated from burning fuel, while a steam turbine burns fuel to heat a closed loop of water vapor which turns the turbine blades. Combined cycle plants can take advantage of both systems by using a combustion turbine with the excess heat from that system being used for a steam turbine. Also, the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978, made financing large scale plants more difficult, while allowing smaller power producers greater access to the grid.

In the 1970s around 75 percent of new generators had a capacity of 300MW or greater. By the first decade of the new millennium that number had fallen to less than 10 percent. As the market has moved away from large-scale power plants, it has accelerated small scale technologies that can be sites closer to consumers because of their smaller footprint and cleaner generating capabilities.

The trend of shrinking generation can be seen in St. Louis region over the last 50 years through the practices of Ameren Missouri. The utility hasn’t built a steam plant since 1984, when it finished the first nuclear reactor in Callaway County, MO and all of its fossil fuel based steam plants are at least 38 years old. However, they have built over seven combustion turbine based facilities (with multiple generators at most) since 2000 to bring total combustion turbine capacity to 2.47 GW. Compare this capacity to Ameren’s largest power plant, the Labadie coal-fired plant, built in 1970 near the peak of large-scale building boom, which can produce 2.4 GW on its own (4 generators make up this plant).

Ameren’s largest single generator remains the Callaway Nuclear plant, with a capacity of 1.2 GW. A second reactor was envisioned in the original plans, but has yet to materialize, mainly due to the enormous upfront cost required by the utility to make the plant operational. In an effort to reduce the infrastructure cost of large nuclear plants, small modular reactors (SMR) have been proposed. These SMR could be as small as one tenth the size of a traditional nuclear reactor and could be built off site in a standardized format to help reduce costs. Ameren partnered with Westinghouse to try to bring that technology to Callaway in place of a conventional reactor, but the partnership missed out on a federal grant that the projected needed to proceed. However, SMR technology could still be the future of nuclear power.

Other more distributed technologies are being implemented both nationally and locally as well. While wind and solar power get much of the attention when discussions of distributed energy resources are brought up, other traditional technologies are being scaled down in the same way as nuclear. Hydroelectric power traditionally has used dams, reservoirs, and large generators to create electricity, but Boeing has produced a turbine for siting on river bottoms that is powered by the natural river current. Its largest project is being built in Quebec, where 46 of these turbines could produce 9 MW of power from the St. Lawrence River without any changes to the flow of the river. On a hyper local level, houses can buy their own natural gas generators which can connect directly with the utility pipeline for fuel supply, generating anywhere from 10-100kW of power for the home.

All these options mean that both utilities and consumers have many more options for how to generate their electricity. The trend has been for a more distributed network of smaller scale production which has caused utility roles to shift away from power producer into more of a power transmitter and provider. Utilities like Ameren have been selling off power plants to third parties in an attempt help them adapt to the new market structure. As the landscape has changed, the definition of power producers and consumer have shifted. This change has already begun to affect how the electricity grid will look in the future. We’ll explore more on that topic in Part 3: Microgrids.