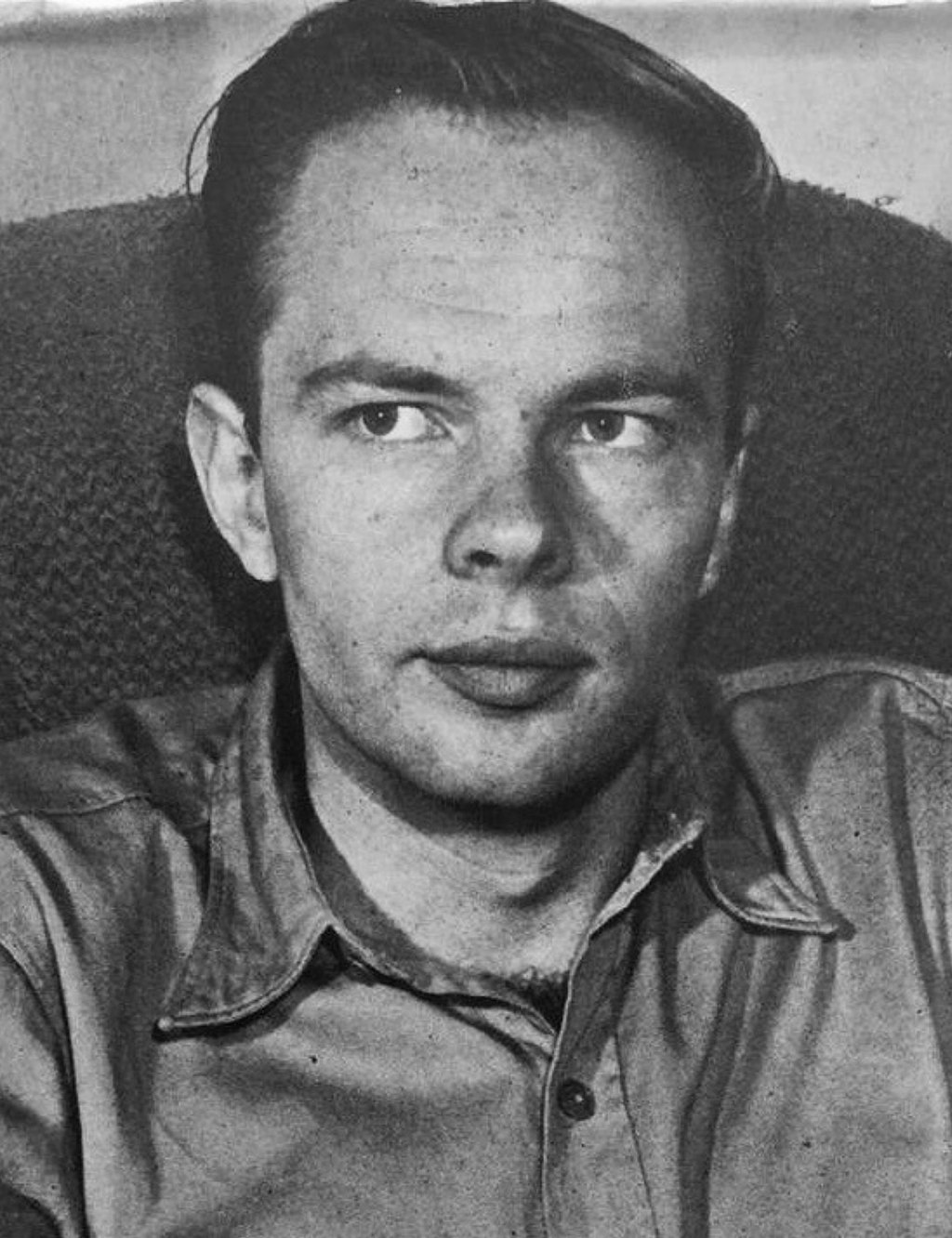

Philip K. Dick in an early 1960s photograph (Credit: ArthurKnight, Wiki)

On this day, the fortieth anniversary of his untimely death, I come to praise Philip K. Dick, not to bury him.

Despite PKD (as he is known to admirers near, far, and wide) only being 53 years old when he passed, on 2 March 1982, from a series of strokes that compounded to fatal intensity, the recognition of his achievements as among the most prolific, most inventive, and most valuable of any American novelist of the twentieth century had already begun. Dick had, by that day, published 44 novels (at least), 115 short stories (at least), and written so many letters to correspondents hither and yon that reading his extensive body of work (or oeuvre, for the proper intellectuals among us) takes nearly one year of happy, concentrated study.

I know because I did so myself. Thanks to the financial support of Washington University’s Department of English and American Literature, I spent most of the year 2001 reading, annotating, and researching PKD’s writing to prepare my doctoral dissertation about the man’s life, career, and art. This project proved so enjoyable and so fascinating that, on the morning of 11 September 2001, Dick’s masterful 1969 novel Ubik engrossed me to the point that I did not realize the 9/11 attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C. had occurred until sometime after 1 pm, when I finally exited the disturbing, unsettling, and seemingly insane world PKD creates in Ubik to re-enter real life, which, in the space of a single morning, had assumed the same qualities.

Many readers have had similar experiences with Dick’s fiction, which speaks to his visionary power to construct subversive narratives that plunge their audiences into waking nightmares so authentic that these same audiences can (and do, as I do) forgive those moments—plentiful in the early going, receding past the horizon as his writing matured—when PKD’s prose falls down the rabbit hole of arid mediocrity.

Dick, after all, lived by the word and died by the word. He chose to earn his living as an artist, always a risky gamble in the United States and a decision that forced PKD to crank out as many tales of wonder, weirdness, and woe as possible so that he could feed his growing family. During his salad days as an author (i.e., the 1950s and early 1960s), funds were so scarce and times so lean that Dick once claimed to have purchased cheap, canned dog food to eat (even if his wife at the time, Kleo Apostolides, pronounced this anecdote just one more flight of Dickian fancy). PKD started his career by contributing to the science-fiction-and-fantasy (SFF) magazines that glutted the market in those days, enduring years of furious writing, minimal copyediting, and almost-instant publication, often for one-cent-a-word (and sometimes for less).

Earning a pittance on short stories with glorious pulp titles like “Beyond Lies the Wub,” “Oh, to Be a Blobel!,” and “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale,” Dick made little more for his early novels, the first of which, 1955’s Solar Lottery, was published as an “Ace Double” (meaning it was bound in tête-bêche format, back-to-front and upside down with, in this case, Leigh Brackett’s The Big Jump). Dick’s surprisingly fine first novel netted him perhaps $400 (some sources say less) at a time when Ace Books editor Donald Wollheim paid $1,500 (or so) for his company’s double-issue quickies.

So, for years and years, commercial and critical success eluded Dick despite his desire to be taken seriously as a literary artist. That’s no longer the case, as his virtual canonization by the Library of America attests (see its three PKD volumes published in 2007, 2008, and 2009), so we must thank the generations of family members, fans, scholars, and filmmakers who helped reclaim Dick’s writing as American literature worth reading, teaching, and savoring.

And it is worth savoring, particularly in that remarkable fifteen-year period from 1962 to 1977 when PKD hit his stride, publishing, in quick succession, novels that reshaped not merely his reputation within the field of American literary science fiction but also that field itself. The Hugo Award-winning The Man in the High Castle (1962); Martian Time-Slip (1964); The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965); Now Wait for Last Year (1966); Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968); the aforementioned Ubik (1969); Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (1974); and A Scanner Darkly (1977) are only eight PKD books of this era, novels so finely crafted that they yield new secrets and additional wonders every time you read them.

You probably know that Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was adapted by director Ridley Scott, screenwriters Hampton Fancher, and David Webb Peoples, its hardworking production crew, and its talented cast (led by Harrison Ford and Rutger Hauer) into 1982’s now-classic film Blade Runner. Dick, in a sad turn of events, died less than four months before Blade Runner’s 25 June 1982 premiere, having been astounded by twenty minutes of visual-effects footage—including the spectacular opening sequence—that Ridley Scott screened for him on Warner Brothers’ Los Angeles studio lot in late 1981.

I came to Dick’s fiction, as so many people have, by way of this movie. At ten years old, Blade Runner overwhelmed me, a film I did not fully understand, but that I also could not shake. Seeing Dick’s name in the end credits led me to seek out Electric Sheep, which had been re-issued to coincide with Blade Runner’s release. My mother, who hated the film despite loving Harrison Ford as its leading man (“that one’s too dark and dreary for me, and, anyway, I just don’t like the space movies,” she said about Blade Runner, an opinion she maintained until her dying day), bought a copy for me anyway.

I did not fully understand the novel, either, but that tiny hurdle did not stop me from reading Electric Sheep again and again. Once I became a teenager, I began seeking out as many PKD works as I could find, which was no easy task in those days, when many of his novels had fallen out of print. Thank goodness for public libraries, which were not Public Enemy No. 1 in my small Iowa town despite Reagan-era America’s best attempts to kill them.

I credit three people for giving me an academic career. The Common Reader editor Gerald Early (Ph.D.) and Wash U. literature professor-extraordinaire Dr. Guinn Batten are the first two, both of whom served as my dissertation advisor at different points during that project, both of whom are fabulous scholars and teachers, and both of whom endured draft after draft of what I am sure was dispiriting dross dressed up as scholarly prose. I can never thank them enough.

Who is the third? Yes, you guessed it: Philip K. Dick. His work inspired me enough to devote years of my professional life to it, which, happily enough, resulted in two books (Future Imperfect: Philip K. Dick at the Movies and The Postmodern Humanism of Philip K. Dick) that helped secure my promotion and tenure at the University of Guam, where I still work and where I still introduce students to PKD’s writing. It has been a nice life, and I can say, without exaggeration, that Dick helped give it to me.

Despite these plaudits, we must also acknowledge the depressing fact that Dick was physically abusive to at least two of his five wives (or that he was, in the parlance of the times, a wifebeater). Lawrence Sutin’s terrific—and now-standard—biography of the man (1989’s Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick) confirms these allegations, as does PKD’s third wife, Anne Rubenstein Dick, in her 1995 memoir The Search for Philip K. Dick, where she writes about their troubled marriage in terms honest, tender, and, loving. Anne, in this volume, forgives her husband of his flaws despite refusing to sanitize or whitewash them.

So, what should we make of all this information? I cannot disagree with people who refuse to read Dick’s work once they learn about his behavior, but, on this day, four decades after he joined the ancestors, I find myself experiencing complicated emotions about the legacy of a man that I never met who has still exerted a profound—and profoundly positive—influence on my life.

Meaning that, with full knowledge of his flaws, I still join the thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of readers around the world who mark PKD’s passing with sadness, with regret, and, paradoxically, with gratitude for the words that he left us to ponder and to enjoy.

Farewell, Phil, wherever you may be.