The Rise, Fall, and Uneasy Redemption of the Hit King

The conundrum of a second chance for Pete Rose, America’s greatest baseball hero or scoundrel

By Gerald Early

December 1, 2025

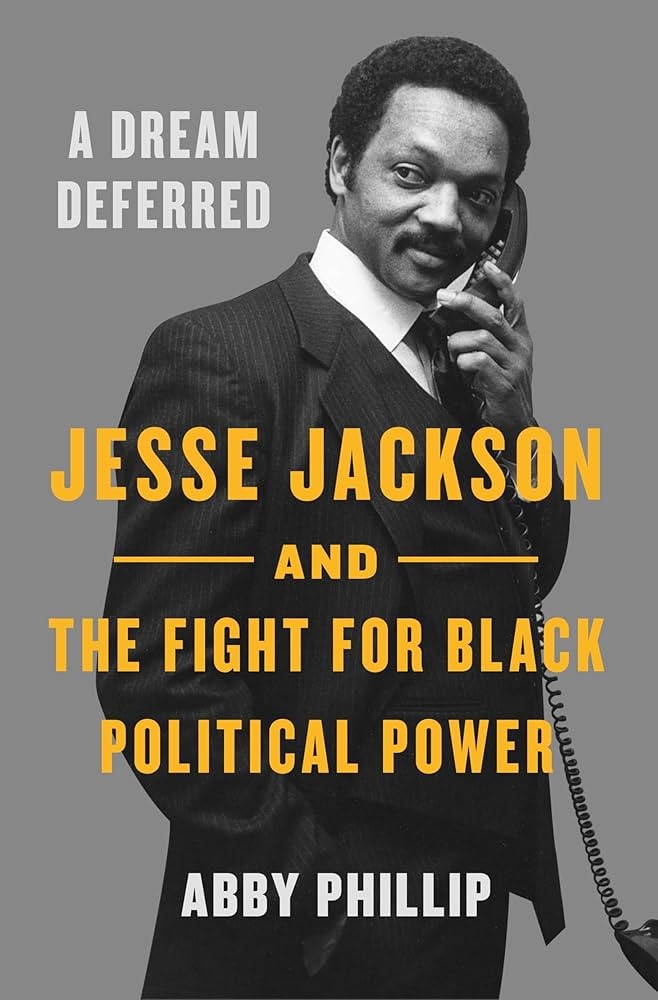

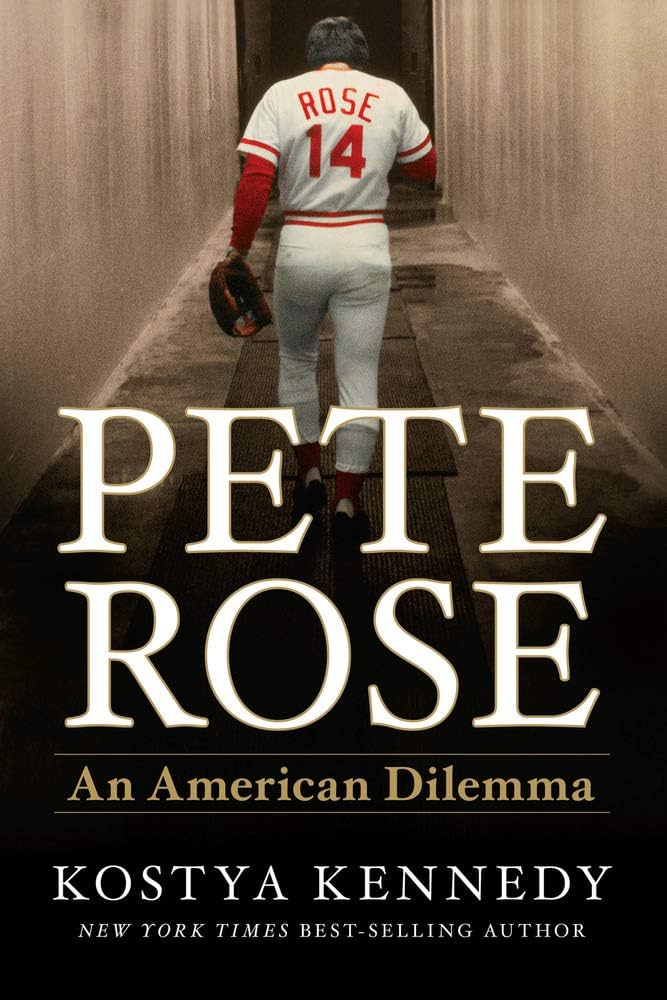

Pete Rose: An American Dilemma

1. Hustle and flow

“That’s the way, you’re supposed to get to first, because the faster you get there, the faster you’re going to touch that home plate.”

My dad didn’t have to tell me twice.

—Conversation between a young Pete Rose and his father, Harry, watching the St. Louis Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter after he worked a pitcher for a base on balls.1

Everyone who knows anything about baseball knows the story about how the Hit King got his nickname. In the 1963 Cincinnati Reds’ spring training camp was a local kid, an infielder named Pete Rose. His father, Harry Francis, also known as Pete, had been a hard-nosed athlete, tough and passionate, a mini legend in Cincinnati, playing semi-pro football until he was forty-two. He reared his son to be an athlete, nothing else. Pete Rose barely made it through school. “I was never book smart,” Rose wrote in his last autobiography. “I was never one for reading. I didn’t mind skipping out on school and not having to do those lessons…”2 Rose the younger had been something of a football hero in high school but was too small to have any sort of future in it on a collegiate or professional level. But baseball was different and that, too, was Rose’s sport as well as his father’s. In the spring of 1963, Rose, who had spent a couple of years toiling in the Reds’ minor league system with a considerable measure of success, was a long shot to make the major league club as its new second baseman. The team already had a solid second baseman named Don Blasingame. While playing an exhibition game against the dominant and cocky New York Yankees, Rose worked a base-on-balls and ran down to first base. He did not walk or trot; he ran. That is what he and his father saw Enos Slaughter do.

The attitude of most players would be “Why run when you can walk?” Save your running for more important stakes. Rose was different. “Why walk when you can run? Why not run to first even on a base on balls?”3 If you run when nothing is at stake, it will plant in the mind of the opposition just how ferocious you can be when it truly matters, a way of telling the opposition, “I want to win more than you do.” Rose always understood that a large dimension of sports was unrelenting psychwar. When Yankee stars Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford saw Rose run to first, they derisively dubbed him “Charlie Hustle,” and it stuck for Rose’s entire 24-year playing career. By spring training’s end, Rose supplanted Blasingame and became the Reds’ second baseman. And he had the last laugh with Mantle and Ford as he was voted the National League Rookie of the Year in 1963 and would have joined them in the Baseball Hall of Fame except for his own greed and stupidity.

Hustle became his myth, what made him larger than life. Who can forget Rose barreling into catcher Ray Fosse to score the winning run in the 1970 All-Star Game, playing as if it were the seventh game of the World Series; or his being Johnny-on-the-spot to backup catcher Bob Boone in the sixth and deciding game of the 1980 World Series, catching a foul ball that popped out of Boone’s glove. He seemed impossibly attentive to the game as it was being played. As Kostya Kenney writes in Pete Rose: An American Dilemma, “[T]here is only one player among the game’s elite whom we remember primarily for his effort, for his unstinting commitment to playing the game the way that it seems meant to be played.” (206) Kennedy observed correctly that Rose not only elevated his own game but the performance of the players around him. He inspired his teammates, even his opponents. He was an uncompromising player but not a dirty one. Unlike the steroid users in the 1990s like Mark McGuire, Sammy Sosa, Barry Bonds, and Rafael Palmeiro, he did not cheat as a player. He probably did not cheat as a major league manager either.

Rose always understood that a large dimension of sports was unrelenting psychwar. When Yankee stars Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford saw Rose run to first, they derisively dubbed him, “Charlie Hustle,” and it stuck for Rose’s entire 24-year playing career. Rose had the last laugh as he was voted the National League Rookie of the Year in 1963.

Hustle, that ineffable quality of athletic greatness, is about going all out on every play. As Kennedy writes, “It’s just not done.” He quotes former Cardinal and Met first baseman Keith Hernandez, “‘You play through injuries and you play through times when your legs are dead, and you have games when you just don’t feel so well. The reality is that sometimes over the course of the season you have got to save yourself for the long haul. That’s why it’s so rare to find a player, anyone, who truly hustles on every play.’” (203) Rose did. His attentiveness to the game was nonpareil.

Rose was nobody’s natural. He was not a five-tool player, a “can’t miss” prospect. He had a weak throwing arm, no power, poor fielding range, and average speed at best, so he was not much of a base-stealing threat. What he had, which became apparent even while he was in the minor leagues, were amazing baseball smarts, incredible durability (he only missed time for injury twice during his long career), an uncanny ability to make contact as a batter, a willingness to play anywhere his manager chose to put him, the personality to get along with his teammates, the perseverance to practice his craft incessantly day and night, and finally an indomitable will to win. All major league players want to win. They would not be in the majors if they were not supremely competitive men. But Rose was unique, even in this specialized group, with how much he would do to win. He made his desire to win a skill and a weapon on the field. As one of his minor league managers, Johnny Vander Meer, said, “Hitting and speed are not his greatest assets. It’s aggressiveness.”4 That made up for a lot of shortcomings as a ballplayer. It made him a star, a Hall of Fame player, as everyone with even scant knowledge of baseball knows, who is not in the Hall of Fame for two simple reasons: he broke the rules of his profession by betting on baseball games and, when confronted, lied about it repeatedly, foolishly, obviously, pathologically.

At the height of his fame, Rose seemed indestructible, a force of nature. Nothing was going to stop him from breaking Ty Cobb’s record for the most career hits by a major league player once breaking it became remotely possible. He broke Cobb’s record in 1985 at the age of 44 in his 23rd year of playing. He had to average an astonishing 194 hits a year over the course of his career to achieve the feat. “Whatever it takes” became Rose’s unspoken motto. It was as if—to borrow Marlow’s words about Lord Jim—he believed “that the unexpected couldn’t touch him.”5 But, alas, it did. He was not bigger than professional baseball, as baseball commissioner Bart Giamatti reminded him when he banned Rose for life from major league baseball, and he was not bigger than his fate. Rose was a hustler, the personality kid, impossibly combining earnestness, innocence, and the bloodthirstiness of a shark; and hustlers always think they can hustle anyone at any time because they are smart and you are a sucker. Hustlers always believe they can outsmart their fate. They always believe that nothing can touch them. That is how they flow.

2. Breaking the unbreakable

He had no leisure to regret what he had lost, he was so wholly and naturally concerned for what he had failed to obtain.

—Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim (1900)6

Nothing bothers me. If I’m at home in bed, I sleep. If I’m at the ballpark, I play baseball. If I’m on my way to the ballpark, I worry about how I’m going to drive. Just whatever is going on that’s what I do.

—Pete Rose, quoted in Kostya Kennedy, Pete Rose: An American Dilemma (90)

Kostya Kennedy’s Pete Rose is a tour de force display of journalism, top-flight writing, and excellent research. It is rich in biographical details, yet it is not meant to be a biography in the typical sense, a comprehensive cradle-to-grave account of a life. The book is more of an exploration of Pete Rose as a celebrity athlete, his rise, his fall, and how he has managed both, or how managing his failures hinges entirely on how well he can throw around the weight of his accomplishments. The question that drives the book is: “Should Rose be admitted to the Hall of Fame?” Everything else about Rose turns on how one answers that question. In some respects, the book poses the same question as Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel, What Makes Sammy Run? What, indeed, does make Pete Rose run? Run to first base on a walk? Run after women as a compulsive womanizer who wrecked his marriages? Run after money in any way he can hustle it? Run after the big payoff by compulsive gambling? Run after the Hall of Fame in desperation for the approval it would confer, the capstone it would bestow on his greatness as an athlete, as what is his due for all the blood, sweat, and tears, the everything, he gave baseball? The subtitle “An American Dilemma” could have been “The American Dream,” because Rose lived the American Dream even as he tried to outhustle it. Rose was hardly ever home during his baseball career because, of course, playing baseball takes up an enormous amount of time and because he was succeeding at getting endorsement deals during the off-season. But he was almost never at home once he was kicked out of baseball as he was trailing a buck wherever he could spot one. Pete Rose was always an extraordinarily restless man, and that may have been a reason for his intensity as a player, for his insatiable gambling habit, for his womanizing, for his garrulous nature (he would talk to anyone). Maybe the American Dream is about the myth, the legend, the heroism, the pathology, of restlessness.

At this point, with Rose’s death, getting into the Hall of Fame may be a huge anticlimax. Perhaps it was always a huge anticlimax. As Kennedy observed about the controversy, “The conflict clearly lends him a cachet, the lure of the unresolved. That people see him as tainted—the outlaw hero—or as a victim of an injustice adds an attraction he would otherwise not have, something beyond his being the Hit King.” (226) The pop culture sideshow that had become Rose’s life once he was banished from baseball—talk radio, selling autographs in Las Vegas, at card shows and at Cooperstown during Induction week, doing reality television shows, selling his time and appearance (Have dinner with Pete Rose for $5,000), this carnival of sleaze, hokum, and cheap thrills—had a kind of heroic and tragic sheen to it. (Rose was always comfortable with the sleazy underbelly of professional sports. Many players are. He was also popular with common working folk like hotel workers, waiters, drivers, and ticket clerks, as he never acted as if he was above them.) The frenetic selling of Pete Rose showed that Rose was still hustling.

He was either the man who refused to be broken by the baseball powers or the man who was completely broken and floundered ever after. Bart Giamatti and especially his successor as baseball commissioner Fay Vincent felt Rose, who so arrogantly and flagrantly bet on his own team, had to be broken for the good of the game. “What we learn in life… is there’s a certain ruthless sense of honesty about life,” Vincent said, “And that is that when you make a mistake you pay.” (178) (Vincent was speaking from bitter experience.) Rose felt, no matter what he did, that he embodied the game. He made the game. Fans did not go to games to see the people who ran the industry or tried to be its moral conscience. They came to see Rose, who had to feel that he was, in this respect, unbreakable. “I owned him that visit. He played his heart out for me,” said former manager Sparky Anderson as he came to see Rose in Cooperstown in 2009 during one of Rose’s autograph sessions. (213) Kennedy rightly notes that Rose’s attitude toward the major league authority figures was, “Fuck you, I’m Pete Rose.” (161)

Pete Rose was always an extraordinarily restless man, and that may have been a reason for his intensity as a player, for his insatiable gambling habit, for his womanizing, for his garrulous nature (he would talk to anyone). Maybe the American Dream is about the myth, the legend, the heroism, the pathology, of restlessness.

Kennedy’s excellent book clears up a few misconceptions. First, when Giamatti banned Rose from baseball in August 1989, it did not make him ineligible to be elected to the Hall of Fame. It was the Hall of Fame itself that passed a resolution to make Rose ineligible for election. Second, in “Evensong,” Kennedy’s afterward reflecting on the 2024 death of Rose, who was 83 years old, he corrects those who think that major league baseball’s current romance with the sports betting industry is hypocritical considering what was done to Rose for gambling. Kennedy writes, “There is no hypocrisy. There is no relationship—beyond superficial optics—between pro sports’ sponsorship of legalized betting and Rose’s sins. The proliferation of gambling may well hurt baseball over time, working to erode the team loyalties and the generational bonding that has been a stanchion of the sport’s popular success, but to suggest that any of this mitigates the severity of what Rose did is to simply, or willfully, miss the point…. Rose fully and unambiguously endangered the game with the way he bet in the positions he held [as player and manager]. That was untenable then, and it would be untenable now. Think of what potentially influenced outcomes might do to fans’ appetite for a sport, to viewership and attendance. Think, even, of how the specter of games being improperly influenced would damage the betting markets themselves.” (239) Does Rose belong in the Hall of Fame? Does he deserve a second chance? Probably. Besides, what is the point in keeping out a dead man? I suppose that is why the current baseball commissioner Rob Manfred in May of this year lifted the lifetime ban against Pete Rose. Will the Hall of Fame lift its ban, too? Or should our sins live on after we have ceased to? Is that not what all the agitation over changing monuments, public namings, and the like is all about? Some sins should never be forgiven or forgotten. Rose’s betting undermined the integrity of his sport. His lying showed that he did not care about the harm he caused. How forgivable is that?

Rose emerged during the era of larger-than-life boxer Muhammad Ali, tennis star Billie Jean King, and quarterback Joe Namath. It was the era of the new American athlete, an age of redefinition. If you were alive during Rose’s playing days, you were immensely grateful for it. If you lived through the 35 years of his downfall and exile, including a stint in federal prison for filing false tax returns, you know that Joseph Conrad was right: “Nothing more awful than to watch a man who has been found out, not in a crime, but in a more than criminal weakness.”7

1 Pete Rose, Play Hungry: The Making of a Baseball Player, (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 15.

2 Ibid, 41.

3 Ibid, 30.

4 Ibid, 74.

5 Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim, (New York: Norton, 1968), 58-59.

6 Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim, 51.

7 Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim, 26.