On the Draining of Swamps

May 4, 2023

“Drain the swamp” just sounded like something Donald Trump would yell, so in all those years of wincing, I never questioned its origins. But now that the nation again faces the possibility of Trump stuffing himself into presidential blue instead of an orange jumpsuit, my mind returns to that hated phrase. Did it come to him spontaneously?

No, it came to his campaign strategists, via a convoluted, century-long path. They seized it as a way for him to announce (and here, my laptop’s keys stutter) his “ethics overhaul plan.”

Trump hated the phrase. “Somebody said, ‘Drain the swamp,’ and I said, ‘Oh, that is so hokey. That is so terrible,’” he confided a month later at a rally in Des Moines. But he agreed to say it, and when he did, “The place went crazy. And I said, ‘Whoa, what’s this?’ Then I said it again. And then I start saying it like I meant it, right?”

Which is how politics seems to work these days.

Still, it is a sly pleasure to learn that the metaphor preceded him by a century, and its first user was a woman. Helen Hunt Jackson was scolding the U.S. government for its treatment of American Indians.

Its next use was by a socialist—a real one—in 1903: “Socialists are not satisfied with killing a few of the mosquitoes which come from the capitalist swamp,” proclaimed Winfield Gaylord. “They want to drain the swamp.”

Another socialist, Victor Berger, picked up the thread a few years later. Then civil rights advocates working with Martin Luther King Jr. used it in their Freedom Budget for All Americans. And in 2006, Nancy Pelosi spoke of “draining the swamp” in ending more than a decade of Republican rule.

Does Trump know any of this?

His people probably just mentioned the other instance: Ronald Reagan using the phrase when impatient with federal bureaucracy. In 2000, Pat Buchanan snapped that “neither Beltway party is going to drain this swamp: it’s a protected wetland, they breed in it, they spawn in it.”

Agree or disagree, there is literal truth in his quote. Our nation’s capital was built on swampland. What Thomas Jefferson labeled “political intolerance” was already dividing the nation. (Could it be that our calmer decades are the illusion, times when our natural chaos is distracted, soothed, or repressed?) At any rate, Congress was broke and fractious, arguing over everything, unable to act. And so, in June 1790, Jefferson sat down to dinner with James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, and they agreed to accommodate the South’s wish for a capital closer to home by building on the banks of the Potomac River. The site was rich with “an inexhaustible fund of manure” (George Washington’s words). The foundation for the capital buildings rested on oozing mud.

Greed and grandiosity kicked in fast. Investors bought up land, anticipating a city larger and more prosperous than London. Jefferson’s first sketches alluded to ancient Rome; the later blueprints had elements of Versailles. The Potomac was expected to connect to the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers,

It turned out to be too shallow—and too hard to navigate.

As historian Ted Widmer wrote in The New Yorker, “Washington may be the only city on Earth that lobbied itself into existence.”

Over time, sewage problems were solved, the stench dissipated, water was diverted into new channels, and appearances improved. Then, in 2006, the water that runs beneath Constitution Avenue rose rapidly, flooding the basement of the National Archives—where the brittle sepia Constitution of the United States is stored.

Upstairs, the vault stayed dry, and the invasion was mopped up—just as it was on January 6, 2021.

• • •

Once Trump heard audiences chanting that scripted “drain the swamp” catchphrase, he added a hashtag, #draintheswamp, and followed with another 154 tweets about swamps. His “ethics overhaul” was a jab at Hillary Clinton, who he claimed had enriched herself through her political position. (Something he, of course, would never do.) But the phrase was sufficiently vague, folksy, and lurid to serve multiple purposes.

After Trump won the 2016 election, one of his advisers promised reporters he would ditch the phrase; it lacked presidential dignity. But dignity never showed up, and the phrase stuck, rebranded to mean ridding the nation of reporters who opposed him, politicians who voted against him, bureaucrats who insisted on adhering to the rules.

Meanwhile, his allies expanded the phrase mean conquering their opponents, stocking the courts with conservative judges, cutting taxes, shrinking the Internal Revenue Service….

Former Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich explained the two swamps it now referred to: the “K Street lobbyist-political corruption kind of swamp” and the “huge elements of power held by people virtually unaccountable—who basically impose their own values and prejudices with very little supervision.” His examples: “Regulators, FBI agents. You name it.”

The push to end all that “excessive regulation” came, the L.A. Times pointed out, from “high-priced campaigns by industry lobbyists, the very swamp creatures Trump railed about on the campaign trail.” “If Trump doesn’t like it, it becomes draining the swamp,” said John Kelly, an expert in language. “It becomes semantically bleached…. It becomes its own opposite.”

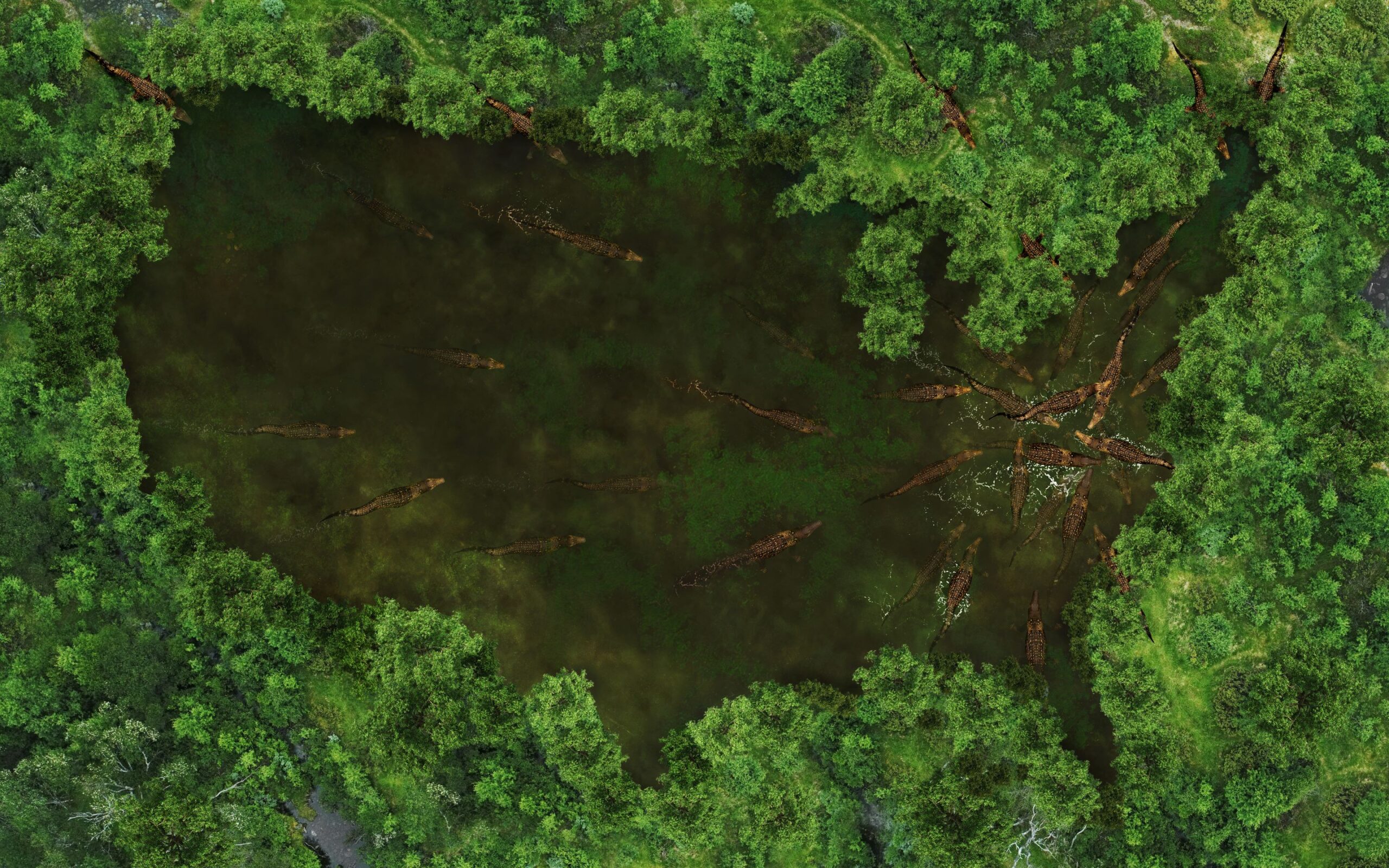

This particular metaphor bends any way you want it to—maybe because its own foundation is not solid. Scientists now tell us “the world needs more swamps—and bogs, fens, marshes, and other types of wetlands.” D.C. was not the only city that covered swampy land with concrete. The world has lost more than half of its natural wetlands, throwing ecosystems off balance.

And so we are left with the richest irony of all: draining never was the right approach. It only sounded good.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.