Of Vacation

December 4, 2024

Well, I am back to being an essayist/journalist/travel writer/critic/blogger/feuilletonist, after a month’s vacation, a word that comes from a root that means “empty” or “free.” Vacated. Ah, but from what?

Despite my time off, the back of my couch is lined with (new to me) half-read books—Dorothy Day, Leslie Fiedler, Adam Zagajewski, Harold Bloom, Diana Athill—their pages open like the wings of hens protecting word-broods. My screen is filled with tabs for Žižek interviews on the election (in reality, always rambling lectures), Wim Wender’s Anselm, Christian Petzold’s Barbara, a friend’s documentary on partisan women, a friend’s novel manuscript, a friend’s memoir chapters on fighting the Taliban. These are the sorts of things I like to spend time with anyway, and could write about, but probably will not.

Of course I did not drop my routines, either: walking, jogging, weights, a hot shower as reward; hot, sweet coffee and leftover greens with salt pork, or toast with jam, for breakfast; phone conversations and occasional light meals with individual friends; all the pets in the world for my elderly cat. Both my sons were home for Thanksgiving, and we cooked for the extended family’s dinner. It even snowed, which has come to seem like too much to hope for in the lower Midwest this time of year. I have certainly written about many of these things before.

If fate gave me a job so well-fitted that when I take time off I do most of what I would do anyway, why bother with vacation? For one, I worked on a novel, intended to be my next book, and coincidentally about imagining what personal freedom means then trying to imagine what to do with it that would be remarkable. Writing fiction, for me, is different from the process of writing nonfiction, so it feels like a break.

Maintaining the perceptive apparatus for nonfiction and holding it professionally always at the ready, through everything I see or do, can be tiring. If I made my living as a novelist, I would probably feel the same about fiction. It is like Lincoln’s old joke about two boys who set loose a brutal hog, because that sounded like fun. One boy was run up a tree, and the other hung on grimly to the tail of the beast as it tried to devour him.

Lincoln says, “After they had made a good many circles around the tree, the boy’s courage began to give out, and he shouted to his brother, ‘I say, John, come down quick, and help me let go this hog!’” He wished to vacate the area.

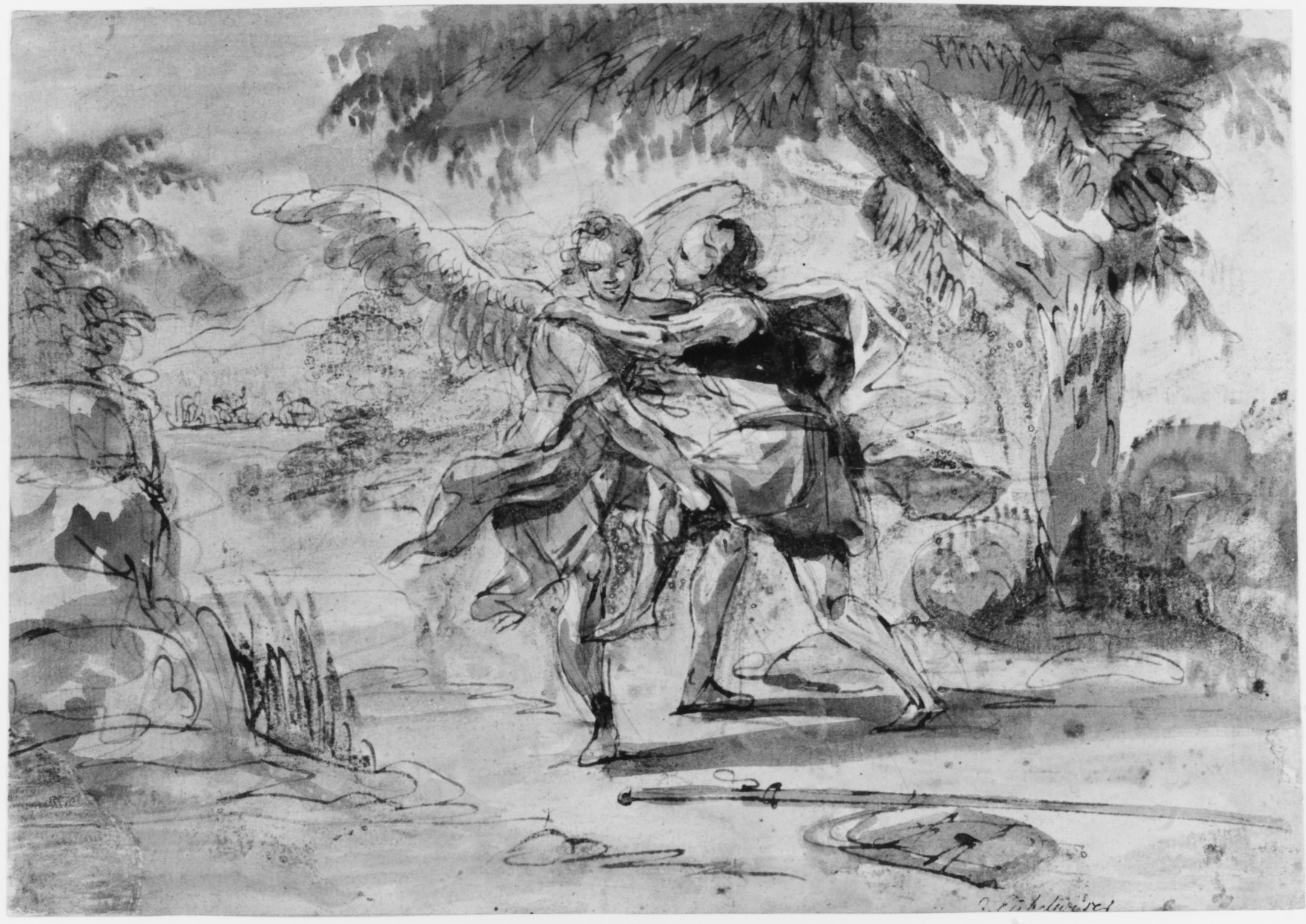

The metaphor could be Jacob and the angel, if you wish. Point is: angel, hog—either way you better be rested.