Christmas music resides along a spectrum wide enough to include light allegories about bullying a young reindeer (John David Mark’s “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” 1949) and masterpieces such as J.S. Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio” (1734). Most of us would be hard-pressed to name Halloween music classics—although lists do exist, and there is lots of kitsch to choose from. Halloween revelers will always do “The Time Warp” (from “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” 1973) again.

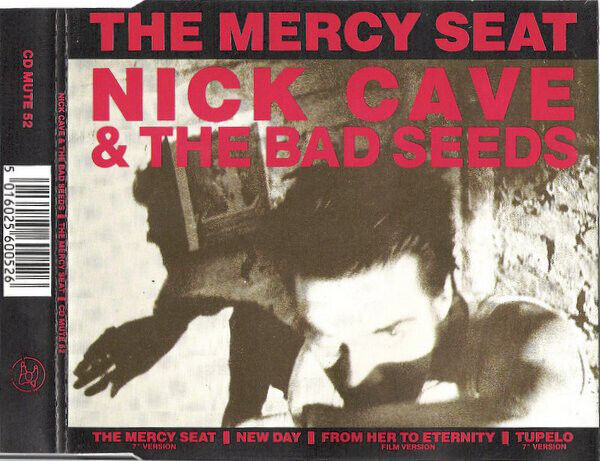

Then there are songs that strike fear into hearts regardless of the month, but carry just a bit more edge than usual during Halloween. “The Mercy Seat,” first unleashed on the world in June 1988 by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, is one of them.

The music of the 1980s has never earned the respect it is due. Locked in the vise grip of yuppies and the Reagan administration, the decade languishes between the boomer clichés of the 1960s and the relative prosperity and calm of the years before 9/11.

Yet the late 1980s were ripe with risk-taking in popular music. Prince was at the height of his powers with the LPs Parade and Sign O’ the Times. Hip-hop was fast ascending to a global musical language thanks to the sonic experiments of Eric B. & Rakim and Public Enemy. Out of New York City’s Lower East Side, Sonic Youth and the Swans were introducing the counter-culture to unorthodox guitar tunings and “songs” that embodied excruciating pain.

Danger, power projections, and playful menace were prized qualities of this new pop aesthetic. If a song or a band did not make you feel that you were standing on the edge of a cliff and looking straight down into an endless descent that song or band was a waste of time. In the late 1980s, the best, bravest bands wanted to write the soundtrack for The End of the World. Or, as Chuck D of Public Enemy put it, “Armageddon has been in effect—go get a late pass!”

The Birthday Party, a group of Australians led by singer-songwriter Nick Cave, was playing a similar tune Down Under with the rollicking, propulsive “Release the Bats,” (1982). Still, it was only a warm-up to “The Mercy Seat,” which Cave co-wrote with bandmate Mick Harvey.

This five-minute (seven if we count the 2010 remaster) tour of a death row inmate’s dirge and final thoughts before death by the electric chair pits an ancient Old Testament object against New Testament teachings, turns everyday objects into hallucinations, and laughs at the idea of knowing truth from falsehood, or justice from mercy, when faced with death. Death solves nothing, resolves nothing, and its only end is an unknowing abyss. Few pop songs are so brutally honest.

“The Mercy Seat” of the electric chair doubles as a reference to the massive, angel-adorned cover over the Ark of the Covenant that houses the Ten Commandments. (Exodus 25:19-22; 37:6) Atonement for the tribes of Israel was possible only when a high priest showered the Covenant’s lid, or mercy seat, with sacrificial blood.

We are used to biblical imagery in Christian hymns and gospel music that glorifies God. Cave, who has acknowledged in interviews that he is held rapt whenever he reads the Bible, invokes such imagery not for the hope of its symbols, but for how they speak to God’s vengeance and people’s malignant motives. (Admittedly, the Rolling Stones’ 1968 hit “Sympathy for the Devil” obviously draws on biblical imagery, but the emphasis is on the character of Satan, rather than imagery. The music matters, too. Where Cave aims for emotions of dread and terror, the Stones seem content to have listeners boogie along.)

Even if built from a fictional inmate, the song reminds us that capital punishment survives to trouble our collective conscience. As he sings, Cave narrates not just the conscience of a murderer reckoning with his own death, but the emerging conscience of anyone chilled by encroaching death. And true to its 1980s aesthetic, the song’s background music sounds like sheets of sandpaper at war with guitar strings.

With “Send Me to the ’Lectric Chair” (late 1920s) and “Lectric Chair Blues,” (1928) blues artists Bessie Smith and Blind Lemon Jefferson penned, respectively, the first known popular songs about capital punishment decades before Cave. Both drape death in sad, bluesy resignation. Smith evokes a woman who knows she deserves death for having killed her cheating husband: “Burn me ’cause I don’t care.”

What Cave lends to this same theme, and at the end of almost every chorus of the song, is a description of increasing dread and a repeated, icy defiance: “And I am not afraid to die.” Of course, anyone who says that again and again is very much afraid of death.

While it is presumably murder he will pay for, the crime committed is not altogether clear. It could be that he committed it as part of a group or gang. Whatever his crime, he has contemplated it long enough, and he has heard prison sermons urging him to repent:

Interpret sign and catalogue

A blackened tooth, a scarlet fog

The walls are bad, black bottom kind

They are the sick breath at my hind

And I hear stories from the chamber

How Christ was born into a manger

And like some ragged stranger died upon the cross

And might I say, it seems so fitting in its way

He was a carpenter by trade

Or at least that’s what I’m told

Penance and reconciliation, then, are not sacraments to be taken seriously. The only “sacrament” is the finality of death. Death in the final hour in which the lid sealing God’s Ark of the Covenant becomes the fiery bolts surging through an electric chair and into the head and body. Even that is a futile tool of justice because there is no such thing as that either, but only wrath. What could be more terrifying?