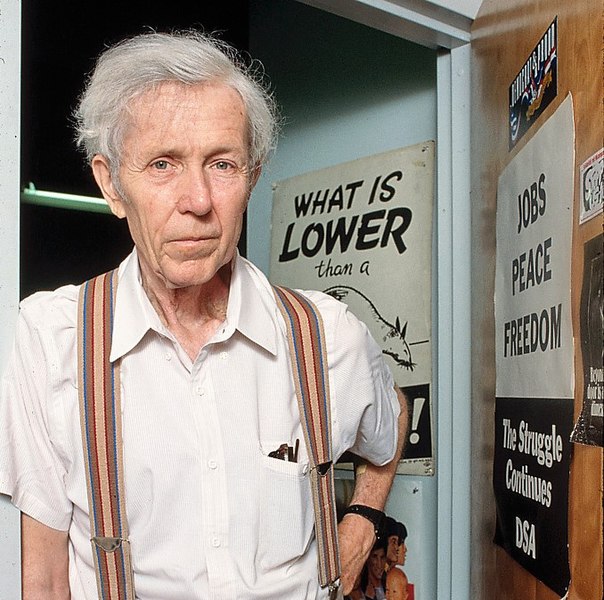

Michael Harrington in 1988. (Photo by BernardGotfryd courtesy Library of Congress)

In 1962 Michael Harrington’s The Other America: Poverty in the United States was published. It was truly one of those remarkable books that fundamentally changed the nature of the debate. Like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring published the same year, it managed to draw attention to a significant but largely unrecognized threat to the country.

The premise was that hidden amidst America’s wealth and affluence was another America. This America was characterized by poverty and despair. It could be found across rural and urban communities, within the young and the old, and particularly among the disenfranchised. Given the backdrop of the supposed economic prosperity of the 1950s and early 1960s, The Other America was a wake-up call for the country.

In a later edition, Harrington wrote that had the book been published five years earlier or one year later, it would not have had the impact it had. President John Kennedy become aware of The Other America shortly after it was published, and it served as a flashpoint in convincing JFK to make poverty alleviation a central goal of his administration. This would become greatly amplified with President Lyndon Johnson’s declared War on Poverty in 1964. At the conclusion of the book, Harrington writes, “The means are at hand to fulfill the age-old dream: poverty can now be abolished. How long shall we ignore this underdeveloped nation in our midst? How long shall we look the other way while our fellow human beings suffer? How long?”

In 1989, I had the good fortune to hear Michael Harrington give here at Washington University what turned out to be his final formal address. Innumerable changes had occurred in the country since the writing of The Other America. Yet the question remained—how long? Harrington spoke that morning with passion and insight. He talked about the changes that were occurring in America—the widening gap in inequality and the increasing numbers of working poor families.

That night, several colleagues and I had dinner with Harrington. It was quite clear that he was suffering from a painful illness and that his days were numbered. Yet the flame was still there, the insights intact. The question still burned—how long? Four months later he was gone.

I have often thought about that encounter. What struck me then as now was not so much what Harrington said that day but how he said it—with passion and concern, in spite of the formidable odds and pain working against him. Why?

My sense was that, in spite of the serious problems plaguing him and America on that day, Harrington strongly believed in this country and was convinced that solid evidence and arguments could make a positive difference despite the powerful forces working against such an approach. He felt that dialogue and an exchange of ideas wer essential to our democracy, and that positive improvement was possible through an understanding of the dynamic changes occurring in our society and through grassroots organizing to confront those changes. Harrington concluded his talk with the following question: “Is it possible for people at the base, for ordinary men and women, to take control of this process of radical change and turn it to the advantage of human freedom? That’s why you have to care.”

Because that is a fundamental question that is posed to this generation.

This question is as relevant today as it was some thirty-plus years ago. Michael Harrington was born in 1928 on this day, February 24, and raised here in St. Louis. I am certain that he would be among the first to protest the wide economic and racial disparities found across our region and the country. But he would also be among the first to call out the morality of a society that permits preventable injustices to cause such harm to future generations. How long?