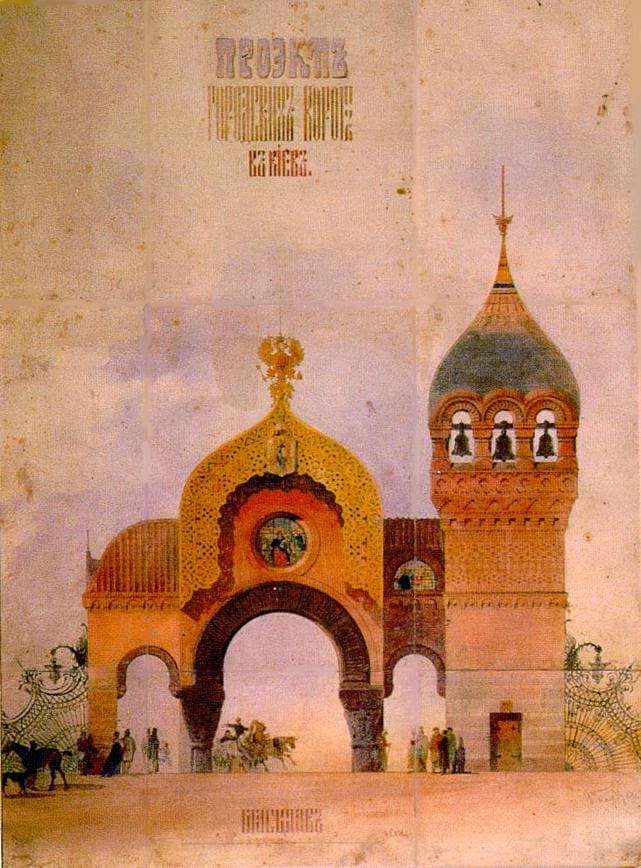

Russian architect and painter Viktor Hartmann’s “The Great Gate of Kyiv.” (Wiki-Commons)

The orchestral arrangement of Modest Mussorgsky’s great piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) is a staple of youth symphonies all over the United States. Or, at least it was when I was young enough to play in the Utah Youth Symphony.

A smorgasbord of orchestral colors spread across an index of varied themes, a carefully rehearsed performance produces thrills out of all proportion to how easy it is for amateur musicians to play. The skills necessary for a pianist to pull off that same sense of excitement are doubtless more demanding.

The background and history of the work, and its composer, are well-known to music buffs. Like so many of his compatriots in music composition during the nineteenth century Mussorgsky was steeped in Russian nationalism and loved his vodka binges. Raised on Slavic folk songs as a child, he was enormously overweight as an adult and enjoyed a passionate friendship with painter Victor Hartmann. Hartmann was no great shakes as an artist but, either blinded by friendship or a stunted appreciation of what constituted good art, Mussorgsky thought his paintings were fit for capturing their essence in musical form. French composer Maurice Ravel, in turn, thought Mussorgsky’s piano suite would sound sensational when scored for an orchestra. Ravel completed that score in 1922, and ever since Pictures at an Exhibition has been plied for television shows and adverts, rearrangements by prog-rock bands, and even Michael Jackson.

The work’s last segment, “The Bogatyr Gates (In the Capital of Kyiv),” is easily the most famous of all ten comprising the composition. So grand that it begs for an extra notch or two on the volume bar, it melds melody with hammer-blow, stately rhythms to such great effect that your hairs do not just stand on end, but march along in time to Mussorgsky’s exalted music. It is a showcase of bombast for pianists, and a theater piece for conductors prone to physical melodrama.

It is also steeped in Russian nationalism. The Hartmann painting that inspired Mussorgsky’s piece was meant to be built in commemoration of a failed assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II. This 1866 attempt was the first in a series of six separate attempts, until Alexander II was at last assassinated 1881 in St. Petersburg by the bomb of a Russian revolutionary. None of the attempts occurred in Ukraine, but like many Tsars before him Alexander II spent a lot of his time warning against separatist movements along with rubbing Poland, Lithuania, and much of Ukraine under his thumb.

Soon after Alexander II survived his first assassination attempt Russians set about honoring his survival with newly built churches and other public projects. Hartmann hoped his painted design (see illustration at top) would also be built in the tsar’s honor. Hartmann’s design is charged with national symbols, including the almost stereotypically Russian onion-dome bell tower and golden two-headed eagle crowning the top of the gate. It was never built. The Golden Gate of Kyiv, however, still stands as a monument to the people of Ukraine and the denizens of Kyiv (see photo below).

Golden Gate of Kyiv (Wiki-Commons)

Russian President Vladimir Putin finds Dmitri Shostakovich is more suitable for propaganda purposes than that of Mussorgsky. Shostakovich’s long, gaunt, unsmiling Symphony No. 7, the “Leningrad,” (1942) was composed as a soundtrack of Russian resolve against Nazi Germany. This fits hand-in-glove with Putin’s absurd charge that Ukraine was worthy of invading because it is a country brimming with Nazis and their sympathizers.

Music may affect sentiments that somehow interlock with individual aesthetic tastes, but it cannot form thoughts or beliefs in any calculated way. And it cannot alter physical reality in all the horrid ways that war can alter it. Mussorgsky’s music represents a tsarist, imperial vision of what Hartmann, and no doubt other Russians, wanted to see constructed so that it could adorn the capital city of Ukraine for generations. When we listen to Mussorgsky’s music we can instead, for now, call to mind the Golden Gate of Kyiv that still stands.