Howard Coale, unpacking treasure. (Photo by Kate Munsch)

The world knows Howard Nemerov as twice the U.S. Poet Laureate, winner of the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, a distinguished professor and poet-in-residence at Washington University for twenty-one years—and a bit of an enigma. A stylist impatient with literary pretension; a deep thinker who held up wit and irony as a shield, then forged on. “Romantic, realist, comedian, satirist, relentless and indefatigable brooder upon the most ancient mysteries—Nemerov is not to be classified,” Joyce Carol Oates once warned.

We know that he was the older brother, often disapproving, of the brilliant, deliberately shocking photographer Diane Arbus. That he was married, lifelong, to a woman he fell in love with when he was an Air Force pilot and rescued from World War II. That they had three children, the middle son being the art historian and writer Alexander Nemerov.

But until now, the world knew nothing of his twenty-year love for a woman from Philadelphia named Joan Coale.

Well, one nosy lady who saw him with “his girl” at the Breadloaf conference had a suspicion. But that single stray piece of gossip—and the intimate knowledge allowed to Joan’s children—was it. Joan [first names for everyone but Nemerov, to avoid confusion] guarded the secret her entire life. With the same care, she guarded his letters, knowing they had a larger significance as outpourings of one of our finest literary minds.

Nemerov died in 1991. His wife died twenty years later, in 2011. But Joan lived on, the letters still safely hidden.

“She didn’t want to be a part of this,” explains her son Howard Coale. “She was not ashamed at all, but she was a shy person.” She left him instructions—repeating them often—to give the letters, after her death, to the archives at WashU.

Joan lived to the age of ninety-seven; she died last February. As soon as the immediate grief lifted and Howard had her other possessions (all those books!) sorted, he felt quiet enough to turn to this. He spread the 513 secret letters across the dining table, and with the help of his wife and daughter, began to group them by year. They read bits aloud to one another as they worked.

“He sounds like an awfully sweet man,” Howard’s daughter remarked. The letters were kind, intelligent, more touching than scandalous. Neither Howard and Joan had been the effusive sort, and both were terrified of hurting Howard’s family. As a result, even their private correspondence was, with a few riveting exceptions, discreet.

But the longing came through.

*

Alexander Nemerov, Vincent Sherry, and Howard Coale (photo by Kate Munsch)

The official transfer of the 513 letters, still in their original envelopes, takes place on campus February 13, 2025, in Olin Library’s Special Collections Reading Room. Howard arrives first, thrilled to be present and elated to be doing exactly what his mother asked of him.

For Alexander Nemerov, though, news of this twenty-year relationship has come as a jolt. When Joel Minor, curator of the university’s literary collection, invited him to attend this small ceremony, he sent a gracious reply and made arrangements to come. But will he show?

Howard pulls out the letters and stacks them atop a display cabinet, covering its surface. Then he meanders through the exhibit of materials from the Howard Nemerov Papers that Minor has prepared for the occasion. Nemerov’s scribbled edits, his awards, even an inexplicable black-and-white photograph, in his World War II pilot’s uniform, with a bottle-fed piglet….

A man enters. Handsome, slighter than his father, graying, with sensitive features. He greets the archivists, chats a bit. Then Coale approaches.

“You must be Alexander.”

Howard has has done illustrations for the New Yorker and published a novel to considerable acclaim. Alexander, also an acclaimed author, is a professor of art and art history at Stanford. If these two men met in a pub, they could talk easily. But this occasion carries its own constraints.

Making the first overture, Howard asks if Alexander has any immediate questions.

“Well, first I have to just make sure that you are not my brother,” he says dryly.

Grinning, Howard assures him that he was born, and named, years before his mother ever met Howard Nemerov.

As the two men compare notes, the conversation relaxes.

“I had no idea how you would respond,” Howard confides. “I felt a little concerned about upending people’s lives.”

“As I’ve told friends, I knew he had a woman in every port,” Nemerov half jokes. “I don’t think that was literally true. I think this knowledge has replaced that.”

“Well, she flew a lot of places to meet him.”

“She was the woman in every port.”

His response to all this is softening, Alexander adds. On the flight here, he read a letter in which his dad wrote to Joan, “Alex is such a tender spirit, for all his dour demeanor.” That phrase “tender spirit,” touched him deeply.

And the dour part? He admits it the way his father would have, with a wry caveat: “I always tell my students I’m the happiest of the Nemerovs.”

They peer at the exhibit the archivists have arranged. “That’s my drawing!” exclaims Howard, pointing to a cartoon he once did for Nemerov.

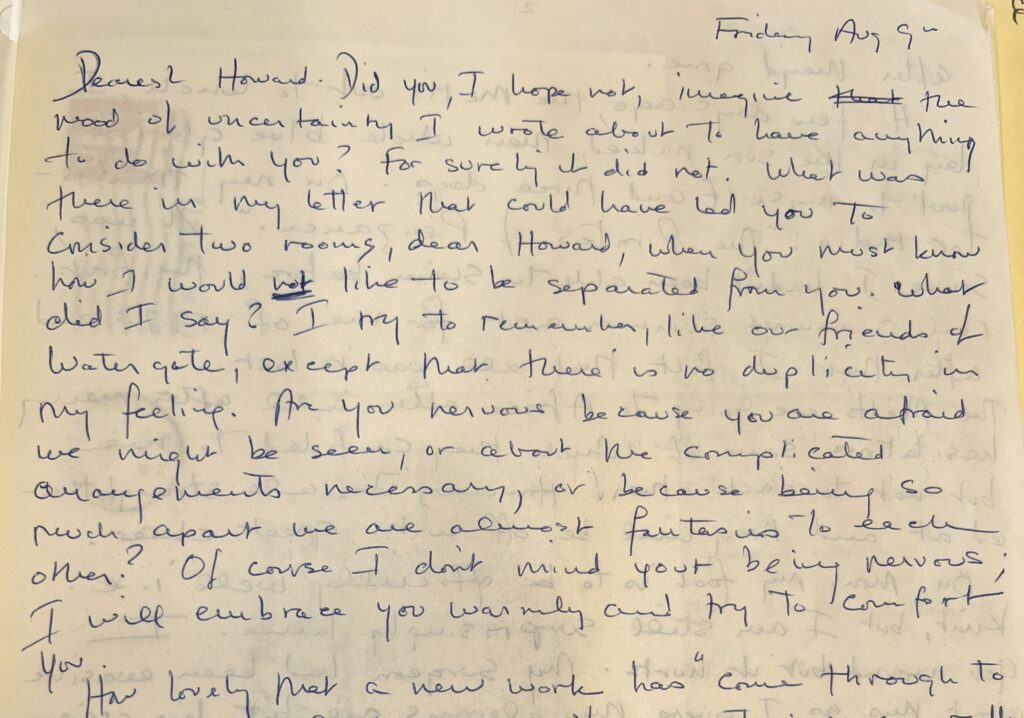

From one of Joan Coale’s letters to Nemerov

Another folder contains twenty-four letters from Joan. Minor found them in the Howard Nemerov Papers—but where all her other letters are, no one knows. Nemerov wrote to her sometimes three times a week, and he often quotes from her letters in his replies. Did he destroy the bulk of her letters to make sure his secret never hurt anyone? If so, why keep the handful of letters, amidst all her friendly, innocuous chat, in which she acknowledges the tension of their relationship and admits how lonely she is for him?

*

As far as Howard can tell, Nemerov met his mother at a University of Pennsylvania literary event in late 1971 or, the year of the first letter, 1972.

Alexander admits to some ambivalence about this correspondence. “Those years I would describe as not very good in our house,” he says, his voice tight with memories.

Nemerov had just lost his sister, Diane Arbus, to suicide. His wife may have struggled too hard within herself to be much comfort. She and Nemerov met in England and married when she was just nineteen—and the marriage to an American allowed her to escape the war. She “was a very traumatized individual,” Alexander explains, damaged, and prone to keeping a lot inside. The Nazis had tried to kill her for four years, he says, yet “her own childhood was bad enough that the war had come as a relief.” Her mother followed her here and was a bit of a tyrant; she lived with the Nemerovs for a time, and Alexander remembers his dad calling her Queen Lear. “So yeah, my mother had troubles, some of which were my dad, for sure.”

“That was true of my mother, too,” Howard says quickly. “My father was a famous womanizer and did not keep secrets about it.” How these very smart, very thoughtful men damaged the lives of the women they loved is something he still works at understanding.

For Alexander, too, this is a chance to sift through childhood feelings. “My older brother doesn’t want to be here. Whatever battles he fought with my dad were different from me. He’s thirteen years older.” But for Alexander, the sifting is a way “to come into the realm of the true, which is probably always joyous no matter how emotionally complicated it is. Some people have said, ‘Why would you go?’ But I think—famous last words?—I’m kind of past the point of embarrassment.”

He is curious how Howard learned of the relationship. Howard explains that he was the youngest child, and after his parents were divorced—a rough divorce, painful for everyone—his siblings all left home. “My mother and I lived alone together. We were very close, and it was pretty hard to hide from me what was going on.” At sixteen, he came home one day to find a tall, craggy man sitting in their living room nursing a glass of—“whiskey, I guess.”

“Or a martini,” Alexander suggests, knowing his father’s penchant.

Asked if he approved, Howard says, “Yes, because it made my mother happy. She’d been treated pretty badly by my father.”

Nemerov struck young Howard as “compassionate and very much present. Some of the earlier men my mom dated, as she tried to put her life together again, were scholars, and a lot of them were very pretentious. He had this sense of warmth. I liked talking to him—he didn’t pontificate. And I liked his handshake. Very strong, but not torturing.”

Howard met Nemerov many times over the years. “I’d go off with my mother to the Academy of Arts and Letters meeting in New York, and we’d go out to dinner with him.” Joan spoke of him often—“sometimes disapprovingly of his drinking and smoking, because my mother did neither. She loved him dearly, I could tell—the way my mother loved people, by first celebrating their faults!”

Nemerov even blurbed Howard’s first novel—in 1991, while battling cancer.

“He gave me a copy of your book,” Alexander recalls suddenly. “But he didn’t bother to acquaint me with who you were.”

Alexander wonders aloud if he ever met Joan. He remembers a poetry reading in New York, his dad groaning over the grandiloquent introduction, and people lined up for miles afterward to have him sign their book. “I remember he strolled away with a woman.”

“Red hair?” Howard asks.

“She may well have.”

• • •

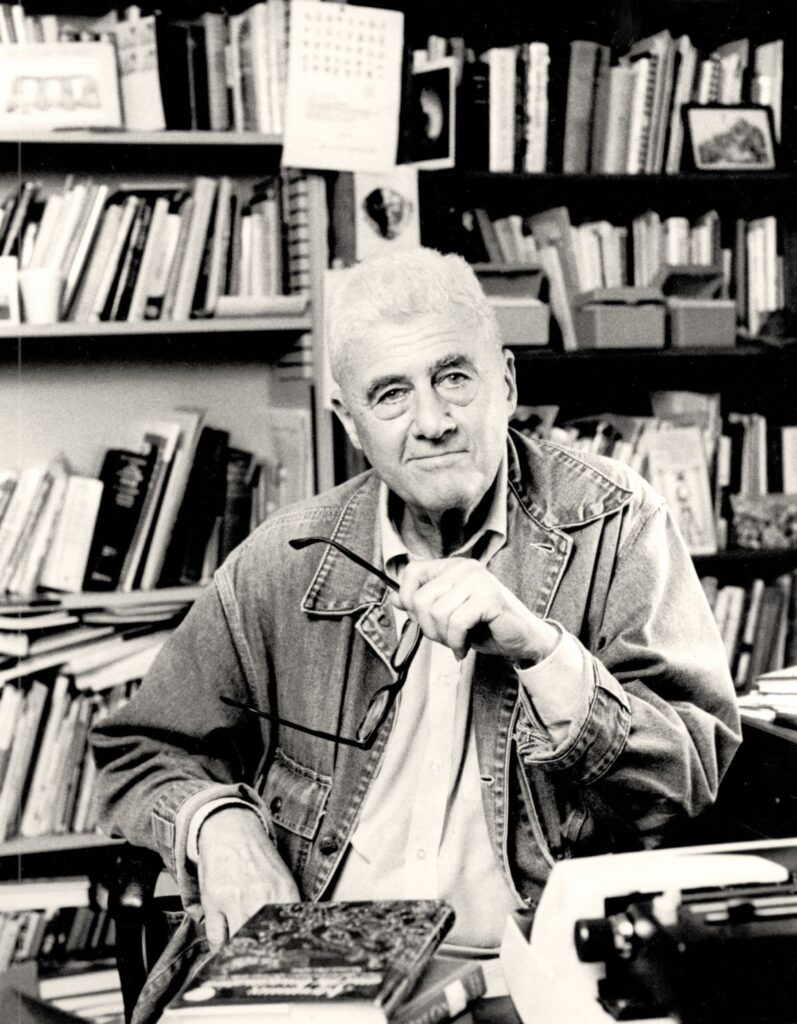

Howard Nemerov, photo by Herb Weitman

Nemerov’s letters to Joan are a delight of self-deprecation. He admits going to the office on the days the cleaning lady comes, because he has “always been put off by the help…and always rather feared they would dust me without even noticing.” He mocks his own fame dryly: after a discussion on some impossible exam, he confides, “I never gives exams, meselph, and am allowed to get away with it because of being so very venerable.”

When Joan does not understand the lit-crit use of the word “levels,” he assures her there is “no need for embarrassment” and blames “T.S. Eliot, who is responsible for that word’s having become some kind of cant term in literary talk at present. It’s true, that when I hear the word much used I think of a department store and imagine my own level as the bargain basement. And there was that lady at the U of Florida last winter who told me that underneath my caustic wit (!?) I was a very gentle person: to which I made reply: that’s fine, dear lady, as long as you remember that underneath that I’m a sonofabitch again.”

We learn he made a “quarterly pilgrimage” to the Mercedes dealership, “that great Kraut brute of a car having developed the curious habit of drinking its battery water in a matter of two days per filling.” (Alexander remembers another car, the one his dad named Allen Ginsberg because it would break down all the time.)

We learn something of his process—“My filing system exists chiefly in my imagination”—and his stuck periods. “o dear, he began humbly in lower case, it’s awful to think of you being sad on my account,” starts one letter. “The depression I meant referred not to life in general, not to love in particular, but to being unable to write and feeling in consequence lost and useless. The self that does my books, or as it is nowadays the self that doesn’t do my books, is a very selfish one, and when it’s out of sorts it can’t be consoled by anyone, not even you, you darling. It just has to work its own way out of whatever it is by waiting glumly….”

The affection he feels for Joan comes through in every letter: “Thank you for being, for meaning so much to me—it gives a good, deep feeling which lasts, as alas it has to do, a long time.”

He tosses compliments lightly, mainly as backhands to her serve: “Dear sweet woman, though ‘high level banality’ is a good and characterizing phrase, I don’t think you’re often guilty of it.”

One August, he remarks that though summer is ending, it is hot still—but it is “a reliquary heat.” As he once wrote in a more formal, public setting, “Poetry is getting something right in language.” He takes the same care with the mundane that he takes for publication. There are gorgeous metaphors and analogies, offhand, in nearly every letter. And this is just the sampling Howard sent ahead of time. Five hundred letters wait, and many are more personal, so he did not want to broadcast them in advance.

• • •

What can we learn from the few letters found from Joan? That she loves Nemerov’s “mordant humor” and prizes his honesty. She fusses over his health, scolding him for not keeping her better informed. She gives warm encouragement and praise for his work, always.

On one occasion, she has come to St. Louis for a family event (she has relatives here) but has not called him. She stayed—one can hear her giggle—in “a hotel called something like The Cheshire Cheese.” The Cheshire Inn, no doubt. She describes its fantasy rooms and says the bridal suite, she was told, has a bed on a pedestal and a mirror on the ceiling, surrounded by stained glass. “Again a bit of sacred and profane,” she writes. “It struck me that if one had to watch the act as if from above that its final ridiculousness would be all too clear.”

Save for the occasion she sunbathes naked and feels alive again, these are not erotic letters. Their mystique is literary. She asks if Nemerov knows that pious Jews once “did not throw away or destroy any piece of writing lest it contain somewhere on it the name of the lord in the tetragrammaton. (The four Hebrew letters that form the name of God.) “An interesting literal turn on the sacredness of the word.”

Born Jewish, Joan was raised a Quaker. She studied art history at Wellesley and designed fabric and jewelry, then began a master’s in literature in her fifties and made it a life quest to understand all of James Joyce. Her love of literature, art, and music (Bach especially) thread through her letters, as do her curious spirit, openness, and candor. When Nemerov hurts her feelings, she is honest, though a little timid, admitting that she has written and torn up several drafts already, because she knows he hates confrontation. But “if one is hurt and angry what kind of relationship is it if that broils contained?” (Which must have felt a sharp contrast to the pent-up pain of his wife.)

At one point, Joan scolds Nemerov about his recent letters’ essential distance, “a distance that you may well keep from everybody by mail, but that would allow you after 13 years to drift away and not write me any truths. I did deserve better than that, if only because you must have known how much our connection meant to me.”

Joan Coale around 1972, courtesy of the Coale family

After Nemerov stops wanting to return together to a literary event, dismissing “those old people”—of whom she had grown quite fond—she takes this as a personal rejection. “I do feel quite helplessly foolish,” she admits, and later: “I feel profoundly put in my place.” Nonetheless, she plays no coy games. “I’d still love to see you in Washington,” she writes. “We will talk of Michelangelo.” Which has got to be a reference to T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” with its line about “the women come and go/talking of Michelangelo.” Granted, there did happen to be a Michelangelo exhibit that month at the National Gallery. But surely that was only a happy coincidence that completed the quote?

In a later letter, she wants to know “what differences you notice since you’ve stopped drinking. Has it made you more cheerful or less? Has it altered your perceptions? Is it harder or easier to write?”

The relationship waxes and wanes over the years, the correspondence sometimes sounding almost formal, like two colleagues who enjoy each other’s ideas, and at other times filled with desperate longing. Especially on Joan’s part.

“I lay awake during a lot of the night in the most intense awareness of you and feeling a great pain of spirit,” she writes. “The astrologer must have been right who told me that we’d been married in another life, and what a close and wonderful marriage it must have been to torment me with such bonds in this one. You are so much woven into my being.”

There is far more vulnerability in these twenty-four letters than in the few publicly unfolded from Nemerov. Once, she tells him, her daughter Hannah found her weeping and said briskly, “You’ll just have to face the fact that you’ll always love him.” Joan adds, “But she understands very well that I am alone too much.”

When he is shying away from a trip together to New York, she writes with her customary frankness, “Are you nervous because you are afraid we might be seen, or about the complicated arrangements necessary, or because being so much apart we are almost fantasies to each other?” Then she reassures him, telling him to do whatever makes him comfortable, and she will be fine with that. In the next letter, she writes, “Thinking this morning about your nervousness in connection with meeting in New York it comes to me that it is related to that deep involvement with your family, which touches me very much…. It is one of the things for which I love and respect you.”

She admired his devotion to his family, Howard remarks now, “because it was the exact opposite of my father.” Scholars have described the tensions, in Nemerov’s poetry, between his romantic and realistic visions. Here they are in life.

“I’ve many times thought, and said to you in letters, that your love for me was an impediment to your chances—career, another marriage, you will remain beautiful longer than anyone—and that I wasn’t doing enough for you, couldn’t do enough for you, to make up the deficit of a serious and settled life both professional and domestic,” he writes. “But there it is, and here we are, a dozen years after the accident that made us lovers.”

Joan ends free-spirited: “In later life I am learning not to be embarrassed at what I really feel and this is a great liberation so I am really not embarrassed at being drawn to you.”

• • •

In his poem “The Consent,” Nemerov asks, “What use to learn, lessons taught by time”? Both these men, sons of genius, if errant, fathers and of mothers they felt for, are asking that question of themselves. Howard asks Alexander how he will go about reading all these letters.

Alexander smiles and says he is not sure, but he now feels less urgency. Less dread, perhaps. “A certain peaceful feeling has come over me.”

It will be interesting, one of the archivists remarks, to match the ten-year hiatus in the handful of letters from Joan to those years in the letters from Nemerov. The conversation turns to the vanishing art of letter writing, how much letters reveal of the inner life, and how little will be available via text and email for future scholars.

“It raises questions about ghosts, and what the dead want of us,” Alexander says.

“I’ve thought a lot about that,” Howard says, musing about the way the dead still urge us forward, maybe through the bit of their consciousness now embedded in our own.

“You and I, Howard, can readily believe that the dead speak through us,” Alexander says. “I just don’t think my dad would give credibility to that at all.”

“While speaking through you,” Howard cannot resist adding.

As the afternoon draws to a close, Alexander remarks that “this has been a kind of séance, in a way.” Bits of memory continue to surface. WashU staffers recall Nemerov’s signature denim jacket, which went to Goodwill the day after he died, and which the archivists would have loved to preserve.

Vincent Sherry, the university’s Howard Nemerov Professor in the Humanities, talks about how many of Nemerov’s poems “are just so right, they are so contained, humming and throbbing with what is unsaid…. He knew that the limitations of language were the strength of poetry. He knew what words couldn’t say, and he made room for the hush.”

Nemerov’s brand of detached irony might not be trending at the moment, but his poetry is timeless, Sherry assures the poet’s son. “He’s in the anthologies.” Rather than offer one of those grandiloquent paeans that so pained Nemerov, Sherry reads two of his poems aloud. He knows they will speak for themselves.

As the editors of the Contemporary Authors Biography Series noted, the body of Nemerov’s work is only beginning to receive the serious critical attention it merits.

And his inner life is only beginning to be known.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.