Everyone who knows Christmas, whether they celebrate it or not, knows A Christmas Carol (1843). The Gospel of Luke is, of course, the holiday’s founding text. Just try adapting it for the screen and stage and see what happens. At the risk of sacrilege, but in terms of story itself, it is for the most part static. Dickens, by contrast, gives us ghosts, time travel, the full, vertiginous spectrum of character development, and a campaigning message that never feels forced. It also helps that he wrote in English prose with an eye on commissions, rather than in ancient Greek with its sights on forming a nascent world religion. Dickens did not need to imagine a future audience. He had an audience. He knew the business of writing.

What is not as well known is that England’s best-known prose writer also wrote five Christmas-season novellas, with the proceeding tale, The Chimes (1844), marching past Christmas and straight to the promise of the New Year.

The Chimes shares much in common with its better-known prose brother. As with A Christmas Carol, we get a sharply drawn main character, spirits and goblins, a bit of time travel (although that comes into question), a warning to reform, invocations against utilitarian and Malthusian ideologies, and a final, moving scene of redemption.

Is The Chimes equal to A Christmas Carol, or perhaps better? Not by a long shot. It lacks the architectural symmetry of the earlier tale, and is too unevenly soaked in sentiment, calling to mind Oscar Wilde’s famous quip regarding Dickens’s weakness for forced emotion, “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing.” Nevertheless, this is Dickens we are talking about, a writer so great the potency of his talent seems inseparable from his prodigious work ethic.

Reading this story, it is easy to imagine Dickens borrowing one of his best-known images from A Christmas Carol, then pointing it in a slightly different direction. Here the “ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slily down at Scrooge … with tremulous vibrations afterwards, as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head” becomes a steeple full of “Chimes” (and always with a capital C) that haunt and thrill the mind of a scrawny ticket-porter named Toby Veck.

Where Scrooge is an unrepentant tight-wad, misanthrope, and so blind to others that he has buried his best memories in business, Veck is Dickens’s striving, good-hearted working man: “… a very Hercules, this Toby, in his good intentions. He loved to earn his money. He delighted to believe—Toby was very poor, and couldn’t well afford to part with a delight—that he was worth his salt.”

Veck’s most endearing quality—and the one that makes him more identifiable by far than Scrooge—is his constant struggle to never lose hope in humanity, or in this case the anonymous and almost faceless bustle of the unnamed, but presumably London-based, streets of his English home. Where we doom-scroll through the phone screens, Veck reads of dismal events in the newspaper. Parliament dawdles while working people starve. A woman murders her child, then takes her own life. “I can’t make out whether we have any business on the face of the earth, or not,” he says. “I can bear up as well as another man at most times; better than a good many, for I am as strong as a lion, and all men an’t; but supposing it should really be that we have no right to a New Year—supposing we really are intruding.”

The Chimes act as a sort of anthropomorphized set of mysterious objects. Hearing them at intervals throughout the day, Veck imagines them calling for him to “keep a good heart,” to keep searching for work, or to simply keep on keeping on.

Veck’s daughter Meg is the loyal, long-suffering female character of Dickens’ stock-in-trade. She hopes to marry her long-time boyfriend, Richard, on New Year’s Day. Veck, too, has hopes for her future happiness, and they bond over a meal of tripe, hot potato, and beer on city streets near a set of doorsteps. Richard makes an appearance to greet his future father-in-law, but the mood comes crashing down when an alderman, ironically named Cute, opens the door to tell them all to get lost, and then inveighs against their marriage.

“After you are married, you’ll quarrel with your husband, and come to be a distressed wife. You may think not: but you will, because I tell you so,” Alderman Cute says to Meg. “You’ll have children—boys. Those boys will grow up bad of course, and run wild in the streets, without shoes and stockings.”

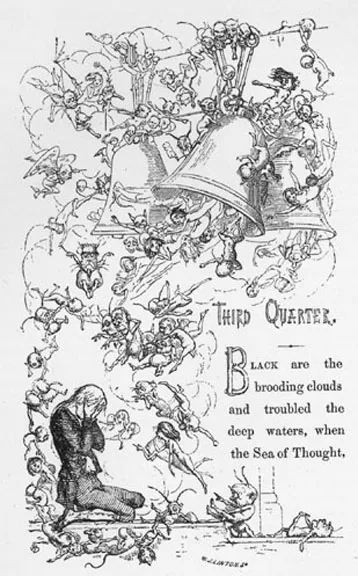

Divided into quarters, at least three-fourths of the story wallows in the calculated depression of the uncaring ruling class that Dickens despised, at least when he sat down to write. Where A Christmas Carol was set in snow, the pure environment of well-meaning ghosts, The Chimes is drenched in mist, damp, and rain. It is the landscape of goblins and infernal spirits, the sort Veck finds in the tower of the bell tower that speaks to his soul when it is troubled. They appear to him in a multitude of visions as indifferent spirits, helping and hindering people who cannot see them. They embody a mind when it is most vexed, when it yearns to impose meaning or design on life.

Hope is a force and sensation Veck longs for, but that he can no longer muster enough energy to find because he has stopped just sort of believing it exists, or that people deserve to live. Even after taking in a man hounded for vagrancy, Will Fern, and his young daughter, Lilian, Veck struggles to understand the message of the Chimes, and what it affirms. It is only when the Phantom, or Goblin, of the Bell speaks directly to Veck that the secret of maintaining hope through time—the capital T “Time” that the Chimes mark—becomes clear:

“Who puts into the mouth of Time, or of its servants … a cry of lamentation for days which have had their trial and their failure, and have left deep traces of it which the blind may see—a cry that only serves the Present Time, by showing men how much it needs their help when any ears can listen to regrets for such a Past—who does this, does a wrong.”

The secret of hope is to keep going, to keep on pushing with an eye on the future. And the secret to keeping hope alive is to live in and amongst time believing in the future.

Many readers find this dime store, “heard it all before” optimism trite, especially those who have experienced true, unrelenting hardship: the loss of a child, prolonged unemployment, struggles with addiction, or lifelong projects never realized. Interestingly, Dickens seems to intuit just these sorts of responses in the storyline. Veck himself risks the loss of Meg, only to have her saved at the last moment. He sees Richard become a vagrant and alcoholic. Without giving away too many spoilers, Dickens demonstrates how a relent to pessimism leads to a long, slow death. Left unchecked, pessimism and cynicism, the negativity of all the world’s Alderman Cutes, pulls us, like a magnet, ever closer to death.

When Veck reaches the summit of clarity in his once confused soul, all thanks to the Chimes, he sees Time, and the coming New Year, as a glorious blank slate on which he is free to write a new story:

“I know that our Inheritance is held in store for us by Time. I know there is a Sea of Time to rise one day, before which all who wrong or oppress us will be swept away like leaves. I see it, on the flow! I know that we just trust and hope, and neither doubt ourselves, nor doubt the Good in one another.”

The Chimes is not likely to be adapted for the screen any time soon, uneven as it is when stacked against A Christmas Carol. But Toby Veck can be counted among Dickens’s great, undiscovered characters. And the story’s warning, amidst our own ongoing sour times, rings as true as its namesake. If the bells of the New Year dispelled all the pettiness, nastiness, and disgust that accumulates in every twelve-month cycle of what we call a year, humanity might have a better chance of renewing its collective force of hope.