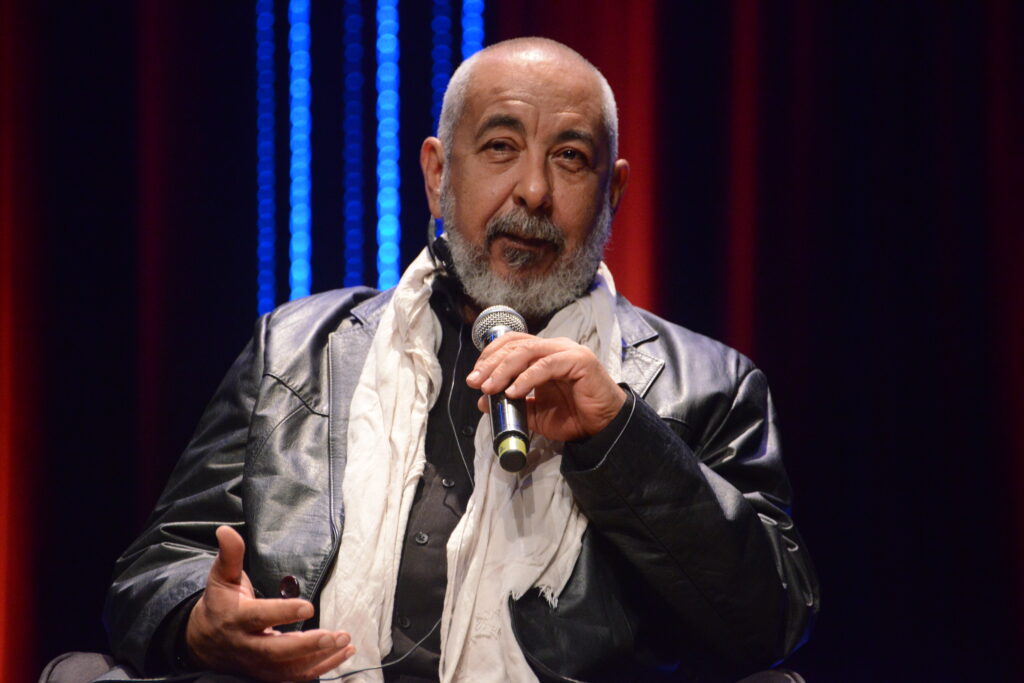

Author Leonardo Padura at the 2017 Fronteiras do Pensamento (Frontiers of Thought) conference in Porto Alegre, Brazil. (CC Photo via Fronteiras do Pensamento)

In 2001, Professor Sklodowska and I taught a Focus course on Cuba which included a spring study trip to the island. Dean Delores Kennedy and others accompanied us, as well as administrators and colleagues.

Leonardo Padura’s Adiós Hemingway (originally published 2001) was part of the curriculum. One day, out of the blue, I decided to phone him. He agreed to come to our hotel, the O’Farrill in Old Havana. We talked for two hours, thus beginning a great friendship. He spoke to our students on subsequent trips. We talked baseball, his first love. Leonardo had played it daily in his native Mantila, a suburb of Havana. He had aspired to be a professional player, but realized that he lacked the talent. He would later write an inspiring book on “la pelota,” and one on salsa.

Padura, born October 10, 1955, began his career as a newspaper reporter for El Caimán Barbudo, and Juventud Rebelde. There he honed his skills as an observer of reality, and as an engaging writer. He published his first novel, Fiebre de caballos in 1988. He wrote it between 1983 and 1984. Set in Havana, it dealt with an adolescent love he had experienced. It is a very different work from the fiction that followed.

Padura decided to write full-time in 1990. He resigned from his government job and turned to write crime novels, inspired by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Edgar Allan Poe, and Manuel Vásquez Montalbán. The four works, Pasado perfecto,1991 (Havana Blue, 2007), Vientos de cuaresma, 1994 (Havana Gold, 2008). Máscaras,1997. (Havana Red 2005). Paisaje de otoño, 1998. (Havana Black, 2006). They are called Las cuatro estaciones (The Four Seasons). Netflix released them as Four Seasons in Havana, starring Jorge Perugorría, the well-known Cuban actor of Fresa y chocolate, 1979 (Strawberries and chocolate, 1995). Padura wrote the screenplay.

Mario Conde, a disillusioned policeman, became a re-appearing character in the manner of Dickens, Pérez Galdós, or Balzac. He became so real to Cubans that when Padura and I were walking in “my” Jewish neighborhood, researching the setting of Herejes (Heretics), people would stop Padura and ask him how Mario Conde was doing. Throughout the novels in which he appears, Conde is loyal to his friends, critical of Cuban bureaucracy, and its enduring corruption. He solves crimes through intuition, not science. Food is in short supply. He drinks and shares cheap rum. He is portrayed as a typical macho. He loves a woman he has known since high school, but he is reluctant to marry her. He is faithful to a mutt called Basura (Garbage). He wants to be a writer, but has writer’s block. He dreams of going to Italy, but never will. In short, Conde is representative of many Cubans and embodies much of Cuban culture. He is Padura’s age, reflects his experiences and deeds, but remains a literary creation that keeps developing in succeeding novels.

Padura has written long, complex historical novels. El hombre que amaba los perros, 2009 (The Man who Loved Dogs, 2014). A fascinating account of Trotsky’s exile to various countries before arriving in Mexico where eventually he was assassinated by Ramón Mercader, a Spaniard, who had fought in the Spanish Civil war. His mother, a committed communist leader, recruited him to murder Leon Trotsky, under Stalin’s orders to kill Trotsky. The novel’s complicated plot involves Diego Rivera, Frieda Kahlo, President Lazaro Cárdenas, the FBI, and many secondary characters. Mercader serves a twenty-year sentence in Mexico. He is rewarded with a medal and an apartment in Moscow. He dies in Cuba where he indeed walks the beach with two Russian dogs. And he tells his story to the would-be writer, Ivan.

Herejes, 2013 (Heretics, 2017), is a symphonic tale in three parts, and a final coda on freedom of choice. It deals with Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewry in Amsterdam, the Inquisition, the trial of Uriel Da Costa, of Spinoza, the paintings of Rembrandt, and the saga of a young Jewish apprentice who paints his own face, (an act forbidden by Jewish Orthodoxy). He is expelled to Poland at the time of the 1648 pogrom. He entrusts his notebook (a taffelet) and some paintings to a Jewish doctor who treats him on his deathbed. Centuries later, the taffelet is bought in London by a relative of the original painter. Heretics includes a long section on Cuban life and culture. He writes in detail about the German liner St. Louis, having sailed from Hamburg in 1939 with 937 Jews. One of them had a Rembrandt painting to barter for his family’s safety. In the end, no one was safe. The St. Louis sailed back to Europe, having been denied entry also in the United States. Padura uses all his narrative skills to tie these diverse historical subjects together amid the complexities and logistics of time and space.

More recently, Padura has published, La transparencia del tiempo, 2018 (The Transparency of Time, 2020), a work set in thirteenth-century Barcelona. A black virgin icon has disappeared and may have turned up in Cuba. Once again, Mario Conde is employed to find the stolen Black Virgin. The investigation will uncover corruption, murder, and the challenges of life in contemporary Cuba. I find the novel’s language elegant and suggestive. It includes some of the best of Padura’s descriptions of places and characters.

Padura’s last novel, Como polvo en el viento 2020 (Like Dust in the Wind), is a rich, multi-geographical, multi-generational, and multi-cultural tale of exiles, family dissonances, estrangements, and coincidences. As in all Padura’s novels, the search for personal freedom of choice is paramount in the complex lives of his characters.

Padura has visited Washington University twice, first as a lecturer in 2012, and in 2017.

Padura has won more than two dozen international awards, the last, the Princess of Asturias prize. On that occasion, he wore a Cuban guayabera and held a baseball when he went up to the podium. First loves never die. Surely, he will be dressed differently when he wins the Nobel Prize for Literature.