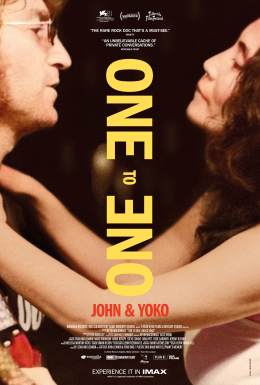

Lennon-Ono Documentary Also a Snapshot of America

August 5, 2025

One to One: John & Yoko (2024), a documentary, was released to streaming this year. The film has been marketed as a kind of concert film, about the only full-length concert Lennon did after the Beatles, at Madison Square Garden in August 1972. The documentary does contain restored footage from that concert, but most of the concert’s individual songs have long been available on YouTube at varying video quality. The documentary’s real interest is the slice of Nixonian America it portrays, and, for the Lennon fan, private photos, film, and taped phone calls I have not seen in previous documentaries such as Imagine.

One to One makes one more attempt to set the record straight on aspects of the couple’s marriage. In the film Ono speaks frankly at the first International Feminist Conference, in 1973, about her relationship with her more famous partner and sings “Looking Over From My Hotel Window,” which should dispel for good the simplistic image of her as mere controlling influence and shouting non-musician.

For his part, Lennon tells a journalist, “I was in the conspiracy [regarding the treatment of women], subconsciously, you know, the same reason as most men are: ignorance. And I fell in love with an independent, eloquent, outspoken, creative genius—for me. I started waking up.”

For fans who wish retroactively for Lennon to have had a meaningful and deeply-lived decade between the end of Beatledom and the end of a life cut short, this documentary will help. It was Ono who convinced Lennon to sell their 70-acre estate, Tittenhurst Park, on the west side of London and move to a two-room apartment in Greenwich Village, where they became even more grounded in their time, activism, and American culture.

Lennon says, “All the time she kept going on about two tatami rooms and possessions and freeing your mind, and I was saying, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah! But, look, you were born rich, kid. You don’t know what it’s like.’ After two years she convinced me. We swapped it all for a two-room loft in New York Village, and we’re as happy as Larry. I feel like a student again. We’re like a young married couple.”

(Remember that line from “The Ballad of John and Yoko”?: “Last night the wife said, ‘Poor boy, when you’re dead / you don’t take nothing with you but your soul—think!”)

The little apartment has been re-created for the film. It is uncanny to see the odd mix of contemporary clips—entertainment shows, Frosted Flakes ads, and news reports on the Vietnam War—on the small black-and-white television that Lennon was fascinated with, because he believed it was a technology that offered a window on the world. The documentary makes smart choices in what to show us from that time, as if we are watching with them. It does not use mere establishing shots, e. g., but actual deaths in the war in collage with Billy Graham suggesting war does not increase deaths. Bob Hope is on yuk-yuk tour with the troops as The Price is Right contestants vie for consumer goods. Many clips are emotional and symbolic: a boy reacting with ecstasy at seeing Nixon on the campaign trail; the presidential limo’s radiator boiling over and pouring steam and coolant; Nixon grinning because he is sure that he is rocking the piano he plays. All of it looks like surreal parody; Lennon and Ono’s “Bagism” protests make total sense by comparison.

What it all adds up to is what Lennon and Ono seemed to have understood well: the banality of normal life can easily go on as madness reigns. And because the film cannot help suggesting a comparison of ’60s engagement with post-millennial numbness, it becomes a bit of an indictment of us, a spreading-around of Arendt’s evil.

It was on this TV that the couple watched a report by Geraldo Rivera on Staten Island’s Willowbrook State School, said to be the world’s largest institution for mentally-ill and intellectually-disabled children, who were left without adequate care, sometimes naked in their own feces, with no one to talk to, raging institutional hepatitis, and feedings of only four minutes each (with consequences including pneumonia and death).

The title of the documentary, then, refers to both the Lennon-Ono relationship and to the concert in the Garden, titled the One to One concert, meant to raise money to improve Willowbrook. (The musical performances in the concert were rawer, in a good way, than I remembered, and weirder: Performers and guest appearances included Stevie Wonder, Bowser and Sha Na Na, Allen Ginsberg, Phil Spector, and Roberta Flack, not to mention Yoko and the Plastic Ono Elephant’s Memory Band.)

The film is often an extended history lesson on ’60s radicalism, celebrity, violence, and state power and corruption. The portrayal of the Lennon-Ono marriage in the ’70s reminds me of Lennon’s statement that, in the ’60s, the Beatles were “in the eye of the hurricane.” He and Ono are shown trying to make a still point in a culture that John Sinclair describes in the film as “being taken over by people who value profits more than they do human life.” (Sound familiar?)

There is some image management in the film’s editing. It leaves out, e. g. , Lennon’s imitation of a gay man on stage at the concert. (He always did, in his discomfort, imitate marginalized people, including the disabled when the Beatles were first becoming famous.) May Pang is shown bustling around in the background, in her pre-Lost Weekend incarnation, which came after the scope of the documentary. And an oddly-constructed sequence of factual events—Lennon being bugged, Watergate, the One to One concert, Nixon’s resignation—seems to imply something more direct about Lennon’s power in the culture that is surely too obscure to be proved.

One supposes the Lennon estate, said to be handed over now from Yoko to son Sean, contains material enough for several more documentaries. This one is dense in texture and worthwhile.